I wasn’t alive when Tom Seaver pitched. The extent of live-action throwing that I saw from him came years later when the time-worn gunslinger threw the occasional ceremonial first pitch at Shea Stadium or Citi Field.

Seaver retired from baseball five years before I was born — hanging up his cleats before what is now a large faction of Mets or baseball fans even took their first breath on this planet. Therefore I feel rather unqualified to discuss such a man.

Yet many of us in the 25-34 demographic nonetheless sit with a pit in our stomachs after the news came down Wednesday night that “Tom Terrific,” “The Franchise,” was gone — dead at 75 after a battle with dementia and COVID-19.

As our fathers and grandfathers mourn the loss of a hero and icon, we also feel that pain — whether it be for them or for the organization that we’ve spent so many summers ardently, ceaselessly supporting.

The Mets have had far more disappointments than success on the field for a majority of its existence. Seaver was the first source of pride for the franchise and a beacon that shone through its darkest days.

We, the younger generations of Mets fans, have been regaled with stories, myths, legends of the man whose long stride toward home plate — accentuated with a dipping right knee that would swipe its way through the dirt of the pitcher’s mound — was as gargantuan as his influence across Queens.

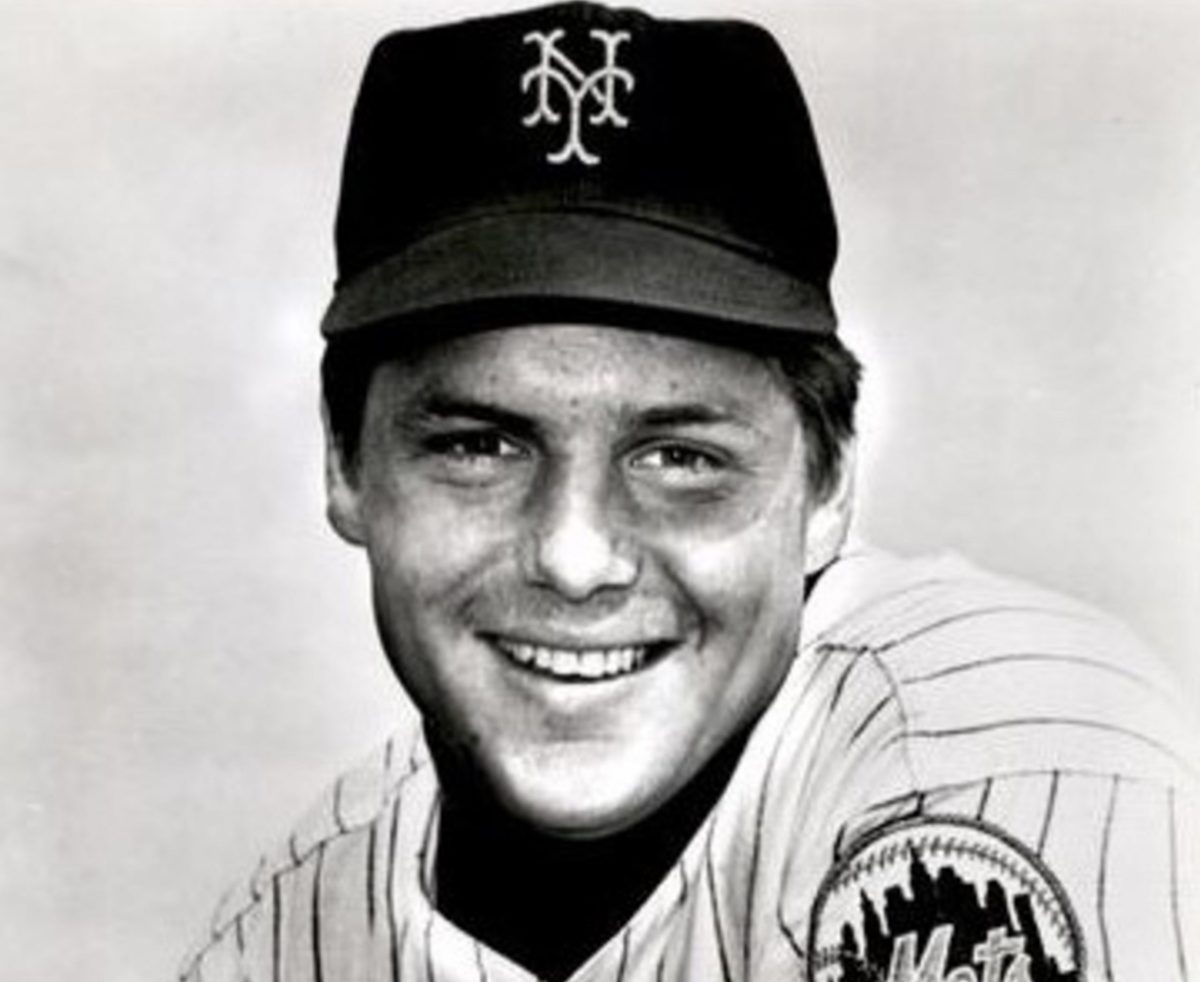

The Mets’ first true superstar arrived on the scene in 1967 and provided positive notoriety for a team that made headlines for all the wrong reasons since its inception in 1962 as a club that found new ways to lose.

Between 1962 and 1968, the Mets went 394-737 before, out of nowhere, they became World Champions.

Their miraculous push to a title in 1969 came on the shoulders of Seaver, who won 25 games and the NL Cy Young Award, asserting himself as one of the top hurlers in the game.

The best game he threw that season turned out to be “imperfect.” On July 9, before a crowd of more than 58,000 at Shea Stadium, Seaver got the first 25 Chicago Cubs batters out, then surrendered a fateful single to Jimmy Qualls with one out in the ninth.

That was the only hit he gave up that night. Footage shows Seaver with his hands on his hips watching the final out of the game fall into Cleon Jones’ glove, frustrated that the perfect game eluded him.

But there was far better glory for Seaver to achieve.

In helping the Mets win the Eastern Division title over the Cubs that glorious season, Seaver was dominant — going 10-0 in his final 11 starts, recording a 1.34 ERA over that span while his opponents batted .170.

Seaver pitched the Mets to their first National League pennant as part of a three-game sweep over the Western Division Champion Atlanta Braves. Then came the toughest test of all — the American League Champion Baltimore Orioles, winners of 109 games that season and heavily favored to beat this juggernaut team from Queens.

We know how that ended.

Seaver lost Game 1 of the series in Baltimore, but then turned around in Game 4 and delivered a 10-inning, complete-game 2-1 victory over the Orioles, putting the Mets ahead three games to one in the World Series. The Mets clinched it with a Game 5 victory, and Seaver got to taste World Championship champagne for the first and only time in his career.

Even with a World Series ring, Seaver never rested on his laurels. The artist took the hill again and again for the Mets and delivered masterpieces for the fans.

There were 19 strikeouts on April 22, 1970, against the San Diego Padres, tying the MLB record at the time.

A second Cy Young Award to navigate the Mets from the pits to another unlikely National League pennant in 1973.

Another Cy Young Award in 1975 saw him become just the second player in MLB history to win the honor three times.

Sadly, the good times in Queens were interrupted in 1977 when a hapless, cheapskate Mets front office traded Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds – refusing to pay their franchise star like the marquee athlete he was. After six years away from Flushing, the Mets — under new management — brought Seaver home as they continued rebuilding from the late-70s doldrums.

Seaver didn’t deliver a Cy Young-worthy performance during the 1983 season, but for fans then, it didn’t matter. His return helped herald the franchise’s second period of excellence.

Two months after Seaver’s return as the Mets’ ace, the team traded for first baseman Keith Hernandez and called up their top draft pick in 1980, outfielder Darryl Strawberry. Another future star for the Mets, pitcher Ron Darling, got to pitch in the same rotation with Seaver for part of the 1983 season — and would occupy The Franchise’s locker after the Chicago White Sox signed Seaver for the 1984 campaign.

Hernandez, Strawberry, and Darling played important roles in the Mets’ success over the following six seasons, helping them win their second World Championship in 1986. They beat the Boston Red Sox in one of the greatest World Series ever played — and, ironically, Seaver was a part of that Red Sox team (acquired mid-season from the White Sox), though he wasn’t on their World Series roster.

After a failed comeback attempt with the Mets in 1987 at age 42, Seaver decided he had enough — and retired. His legacy with the Amazins’, however, lives on.

He’s the Mets-franchise-record-holder in wins, strikeouts, ERA, complete games, shutouts, and pitching WAR.

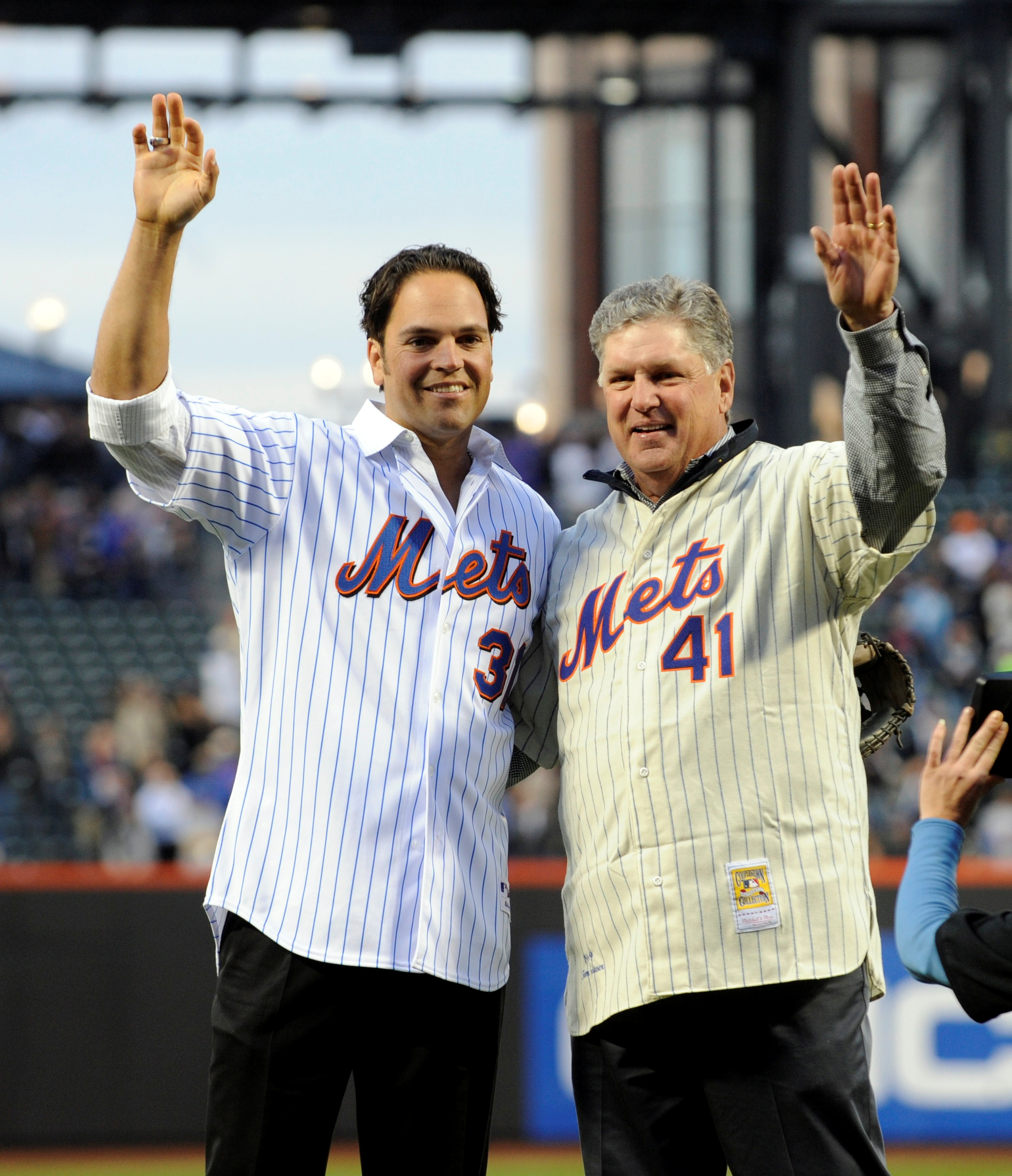

He was the first player inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame while wearing a Mets cap on his plaque, and the only one to do so for 24 years until Mike Piazza was enshrined at Cooperstown in 2016.

Seaver and Piazza served as the battery that closed Shea Stadium in 2008, and opened Citi Field in 2009, with ceremonial pitches.

He was simply the Mets — and the standard by which every Mets pitcher will be measured, now and forever.

And for a game like baseball, which allows its fans that span across the generations to so easily connect with those that came before us, it allowed even the younger Mets fans — plagued by bad ownership, collapses, and an occasional dash of magic — to adopt Seaver as the hero he was to our parents and our grandparents.

Sure, across town the Yankees had Ruth and Gehrig and DiMaggio and Berra and Ford and Mantle. But the Mets had Seaver. And that was more than enough for us.

I’d like to think that somewhere amongst the cosmos, he’s talking baseball with Gil Hodges, Bob Murphy, Ralph Kiner, and Rusty Staub.