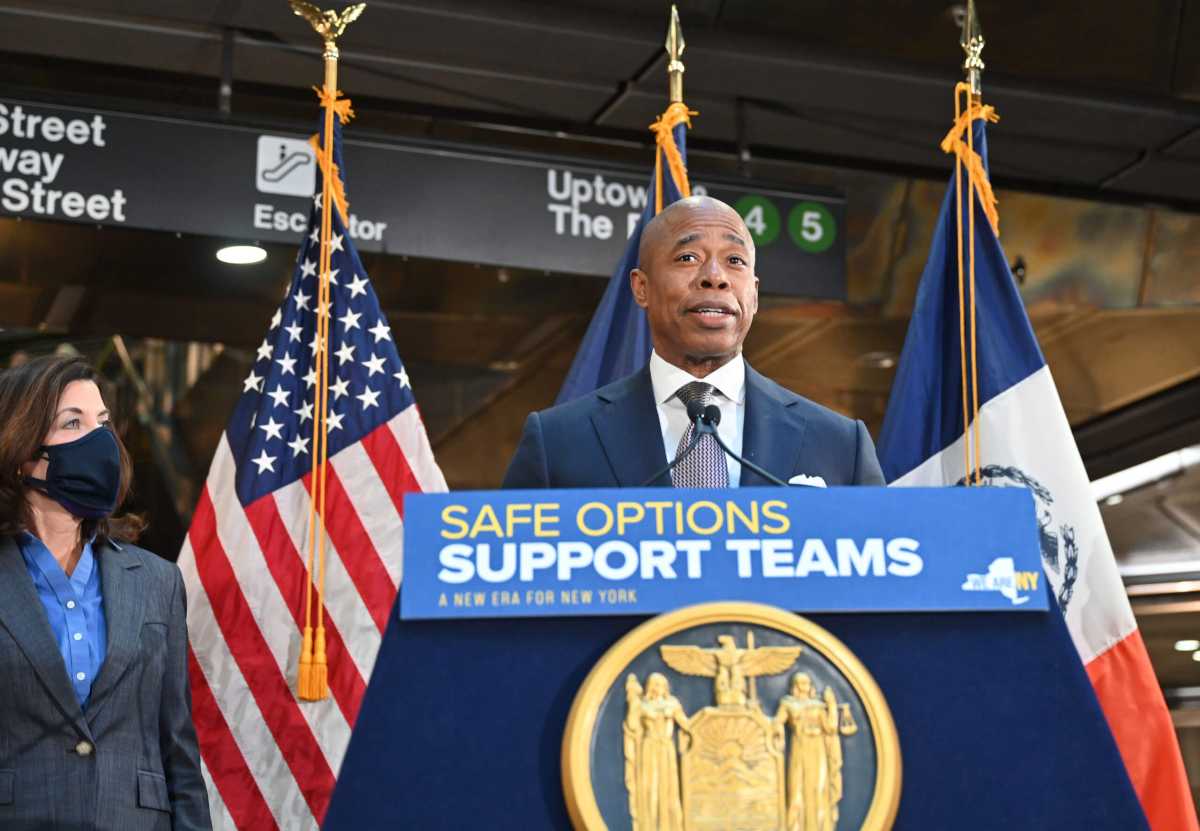

Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul held their first joint appearance since the former took office Thursday to announce a slate of measures to combat crime in the New York City subways and increase outreach to those experiencing homelessness.

Mayor Adams vowed to make NYPD police officers an “omnipresence” on subway trains, using Transit Bureau cops and deploying more above-ground Boys in Blue from the city’s 77 police precincts.

“We’re going to add hundreds of daily visual inspections from existing police manpower,” Adams said at the Jan. 6 press conference in Fulton Street station in Manhattan. “The omnipresence is the key. People feel as though the system is not safe, because they don’t see their officers.”

Metropolitan Transportation Authority leaders have for months been asking the city to station more police on platforms and on trains.

It is unclear how many officers will patrol city’s 472 subway stations, but former Mayor Bill de Blasio boosted the ranks by 250 cops to 3,250 when then-Governor Andrew Cuomo allowed the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to resume 24/7 subway service in May of last year.

That was almost 10% of the 36,000-strong NYPD, even though transit makes up a mere 1.7% of overall crime the city, as Transit Bureau Chief Kathleen O’Reilly said at a December MTA board meeting.

The NYPD’s press office responded to a request for more information with a previously-issued press release that did not include updated deployment numbers for transit.

Recent police stats show there were 169 transit crimes over the last 28-day period, up from 101 the same time last year.

Longer-term trends show that crime has been going down over the past years and decades, with a rate of 4.73 major felonies per day from January through November of 2021, the lowest of that time period since 1997, according to a report the Transit Bureau provided to MTA board members in December.

Gov. Hochul announced she will immediately open a public bidding process through a request for proposal for new state-sponsored homeless outreach dubbed “Safe Options Support” or SOS.

“These are the New Yorkers for whom the system has failed and failure is not an option for us in government,” Hochul said.

The effort will launch with five teams made up of eight to 10 medical professionals, social workers, and other outreach staff to connect the unhoused to shelters and services.

Adams said the initiative will free up cops to focus on actual crimes instead of doing mental health work.

“They’re going to communicate with our outreach workers so they can respond, not to have the officers engage unless there is some criminal activity taking place that needs immediate attention,” he said.

The city’s Department of Homeless Services already contracts outreach workers through the non-profit Bowery Residents’ Committee, but the efforts have been criticized by both the MTA’s Inspector General and the State Comptroller as expensive and ineffective.

Hochul’s announcement was a departure from her predecessor Andrew Cuomo who left outreach service funding up to the city, according to one advocate, who added that the move will only be effective if workers can offer secure private shelter or housing.

“You can have as many outreach teams as you want, but if they are only able to offer people a trip to a large congregate shelter where people are often very concerned about catching the virus that causes COVID-19, many people will continue to remain on the subways,” Jacquelyn Simone, policy director the group Coalition for the Homeless, told amNewYork Metro.

Since Hochul’s RFP process will take time before the new outreach workers board trains, Simone voiced concern that the surge in police will lead to more people without shelter being criminalized.

“These teams will not be up and running for a period of time and yet the police will be surging the transit system, sounds like imminently,” she said. “It sounds as if they will be interacting primarily with police officers and not with trained mental health and housing professionals.”