The Metropolitan Transportation Authority says its proposed redesign of the Brooklyn bus network, which aims to improve the speed and reliability of the borough’s notoriously slow bus service, has been getting pushback from riders across many neighborhoods, many of whom have built their lives around commuting on the existing map.

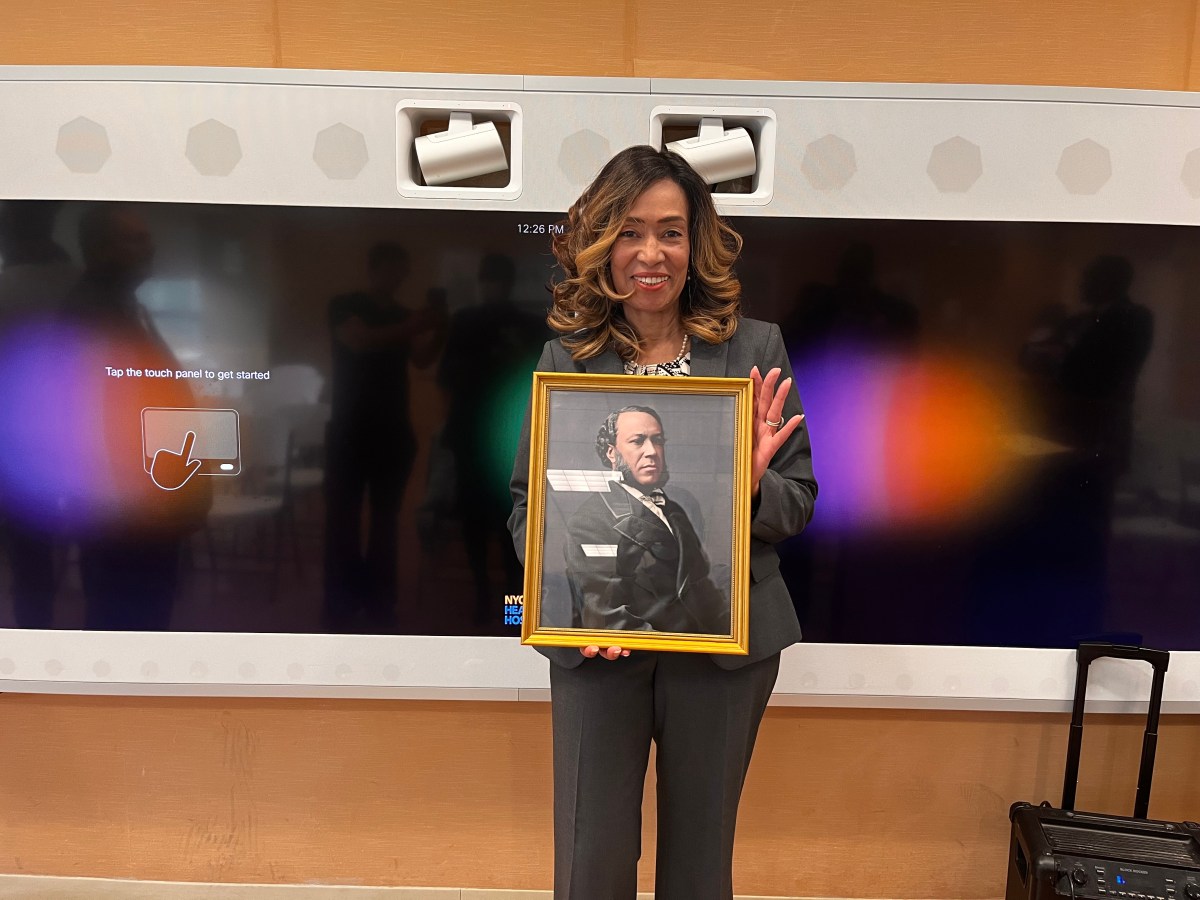

The MTA unveiled its long-awaited draft plan for Brooklyn in December, the fourth such proposal for a borough-wide bus network redesign first floated in 2018 by former New York City Transit President Andy Byford.

Byford, a popular Englishman known by many as the “Train Daddy”, had promised to “reimagine” the city’s ancient bus network, which had been unchanged for several decades, and was still based on the streetcar lines that once crisscrossed the city and inspired the name of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The streetcar lines have long since been ripped out of the ground.

The city’s buses, disproportionately relied upon by low-income residents, are the slowest in the nation, and were averaging just 8.15 miles per hour in February. Bus speeds in Brooklyn are below the citywide average, at about 7.19 miles per hour, exceeded only by the snail-like buses in Manhattan.

The draft redesign incorporates a number of ideas by the MTA to speed up buses, notably increased spacing between stops and a change to some of the routes. Some routes, under the plan, have been eliminated altogether, while other corridors would get new lines.

The redesign also incorporates a new service designation, “Rush,” which would add local stops to “transit deserts” and include express service to major destinations. Other routes are reoriented based on what the MTA sees as more modern commuting patterns, between residential areas and job hubs that may not have existed decades ago.

After a long pandemic-induced delay, the Brooklyn network redesign, which is still just a draft, was presented to the public, which has had the opportunity since January to comment on the proposal online and at public workshops. In many cases, the feedback has been highly critical.

Most recently, a group of elected officials repping northern and central Brooklyn sent a letter to the MTA lambasting the planned rerouting of the B48, which presently runs between Prospect Lefferts Gardens and Greenpoint. The draft plan dramatically changes the B48’s trajectory, switching its northern terminus to Downtown Brooklyn. The electeds — four state Senators, five state Assemblymembers, and four City Councilmembers — say the rerouting destroys a “vital connection” between northern and central Brooklyn.

“We are writing in strong opposition to the MTA’s proposal to reroute and cut B48 service as part of the Brooklyn Bus Redesign draft plan,” the electeds wrote in the letter to MTA Chair Janno Lieber, organized by central Brooklyn Assemblymember Phara Souffrant Forrest. “We have significant concerns about these plans removing a vital connection between Western Crown Heights and Greenpoint without any adequate transit replacement.”

Under the plan, the northern part of the existing B48 route is slated to be swapped with the B69, which presently runs from Downtown Brooklyn to Kensington. Not only will that require a transfer for what used to be a one-seat ride on the B48, but the electeds say the B69 is also slower overall, especially on weekends, while service overnight is nonexistent. The electeds are calling on the MTA to restore the original B48 in the final redesign proposal and preserve overnight service on the route.

Tyree Stanback, the tenant association president at NYCHA’s Lafayette Gardens in Clinton Hill, says that rerouting the B48 — which circumscribes the development on Classon and Franklin avenues — would indelibly shape his commute for the worse. A wheelchair user, Stanback relies on the B48 to quickly get to accessible subway stations, as no nearby stops on the G line accommodate those with disabilities.

“To limit the bus service is like taking away healthcare for seniors and people with limited mobility,” Stanback told amNewYork Metro. “It would really affect how we access services and access our community.”

Also controversial is the plan to increase the distance between bus stops. New York’s bus stops are some of the most closely-spaced of any major city internationally.

Officials and advocates have long called for increasing those distances as a way to speed up buses. But that has not gone over well, particularly in southern Brooklyn neighborhoods with large senior populations reliant on buses.

“You have so many people living here who are seniors,” said State Assemblymember Alec Brook-Krasny at a rally against the redesign last month. “You have people with disabilities, you have people who just cannot tolerate the elimination of one stop.”

MTA spokesperson Michael Cortez said that the public has ample opportunity to respond to the redesign, including 15 in-person workshops this spring after 18 virtual seminars, one in each community board.

“The successful public consultation and implementation of the Bronx Bus Redesign process is a blueprint for improving borough bus networks as Bronx bus riders have experienced shorter travel times, faster buses, and more all-day service, with customers noticing the difference and reporting higher satisfaction with their journeys,” said Cortez. “Listening to the voices of Brooklyn bus riders will be an integral part of the Brooklyn Bus Redesign as the MTA is in the early stages of modernizing the borough’s bus network for more reliable, frequent service with better connections, and we invite everyone to participate in that process.”

The MTA completed the redesign of the Staten Island Express Bus network before the pandemic, when the process halted. The Bronx network plan was completed last summer while the final Queens proposal is expected sometime this year.

In the Bronx, where 258 stops were removed (22 of those were restored following community feedback), bus ridership rose by 6% following the redesign between September and November of last year, according to the MTA. Bus speeds in the Bronx also increased somewhat, though not by much: local buses in the Bronx saw a 2% increase in tempo following the redesign, while 13 routes that saw significant changes sped up by 4%, the MTA says.

Cortez noted that customer satisfaction had increased among Bronx bus riders since the redesign’s implementation, and that wait times had been reduced on 10 routes with more frequent service.

As it is, there’s only so much a network redesign can do to speed up buses on New York’s notoriously congested roads. City leaders and the MTA have lobbied Albany to include funding in the state budget for automated bus lane enforcement (ABLE) cameras, expanding and making permanent a program automatically ticketing drivers parked in bus lanes and blocking the flow of jitneys. Funding for the cameras was included in Governor Kathy Hochul’s and the state Senate’s budget proposals, but not the Assembly’s.

The city’s Department of Transportation is required by law to build 150 miles of protected bus lanes throughout the city by 2026, including 20 miles in 2022 and 30 miles each subsequent year. But it did not even come close to the required benchmark in 2022, installing just 4.4 miles of bus lanes, according to its February Streets Plan update.

Like much of city government, DOT is facing a slashed budget and diminished headcount as Mayor Eric Adams pushes a fiscal policy of austerity. In the first four months of Fiscal Year 2023, the agency installed 47% fewer bus lanes than in the same period the year prior.

Additional reporting by Isabel Song Beer

Read more: MTA Installing Elevators at 15 More Stations