The city is not keeping track of its progress in constructing new bus and bike lanes, despite having statutory requirements to build hundreds of additional miles of them and missing, by a wide margin, the legal benchmarks last year.

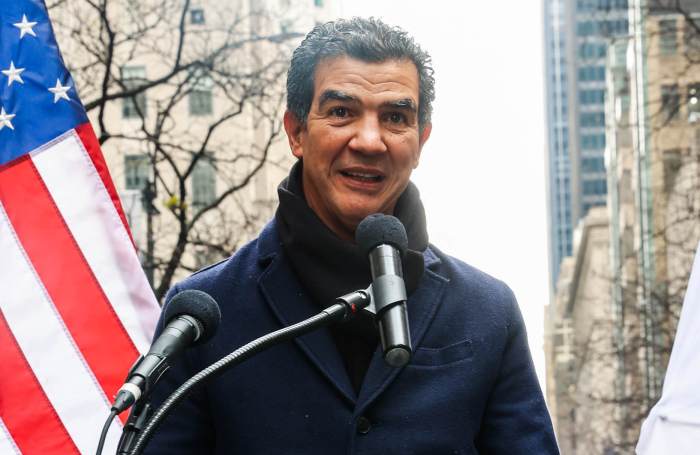

Department of Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez repeatedly refused to provide an answer Tuesday during a City Council oversight hearing regarding his agency’s progress in constructing protected bus and bike lanes this year.

The agency is required under the 2019 “Streets Plan” law to build 150 miles of physically-protected or camera-enforced bus lanes and 250 miles of protected bike lanes across the city by 2026. Last year, the city was supposed to construct 20 miles of bus lanes and 30 miles of bike lanes, with the numbers rising to 30 and 50, respectively, between 2023 and 2026.

The Adams Administration failed to meet that goal, finishing just 4.4 miles of bus lanes and 26.3 miles of bike lanes in 2022, according to its 2023 Streets Plan update. When asked for progress achieved in 2023 by Transportation Committee chair Selvena Brooks-Powers, a Queens Democrat, Rodriguez and Deputy Commissioner Eric Beaton repeatedly refused to provide an answer, saying they could not provide an accurate number during the construction “season” and would have better information come February 2024.

Brooks-Powers described the non-answer as “unacceptable.”

While the administration doesn’t appear to be tracking real-time progress, some advocacy groups are. The advocacy group Transportation Alternatives maintains a tool tracking progress on protected bike lanes and reports that the DOT has built only 10.7 miles of its required 50 miles so far this year.

“There is no excuse for not hitting the 50 miles required by the NYC Streets Plan by the year’s end,” said Brandon Chamberlin, a volunteer with the group who developed the tool. “The administration can meet the requirement by just completing the projects that are currently underway. Failure to do so would be a choice that would betray a lack of commitment to street safety.”

The Riders Alliance, meanwhile, maintains a tool tracking bus lane construction. The Adams administration has completed only 2.4 miles of bus lanes this year, according to the tracker.

“The administration can’t be in compliance with the Streets Plan law without knowing how much progress it’s making towards the mandated mileage,” said Danny Pearlstein, the group’s policy and communications director. “No one is saying they can’t exceed the mandates, which Mayor Adams promised he would do, but they must of course keep count meanwhile.”

Rodriguez said after the hearing that his team would be sending all 51 council members a letter asking them for input on where to place bus and bike lane projects in their respective districts, hoping to defuse community opposition.

The commissioner contended that much of the progress they hope to undertake can be derailed by opposition from local councilmembers. He highlighted the case of the Bronx’s Fordham Road, where opposition from local Councilmember Oswald Feliz, backed by Congress Member Adriano Espaillat, the Bronx Zoo, and the New York Botanical Garden, torpedoed DOT’s effort to build a busway on the thoroughfare, which hosts the busy BX12 line.

In other cases, though, projects are tanked not by outspoken local leaders but from the recesses of the administration. An effort to redesign the dangerous speedway McGuinness Boulevard in Brooklyn from four lanes to two, with protected bike lanes, ran into opposition from both Mayor Eric Adams’ top advisor, Ingrid Lewis-Martin, and a top campaign contributor, the local soundstage company Broadway Stages, which has spent lavishly to defeat the project.

The mayor ultimately ordered DOT to return to the drawing board, which led to a compromise proposal being unveiled in August. But last week, the administration again delayed work on the redesign to conduct a traffic study of the boulevard’s southern portion.

“We’re at a point where it’s all politics all the time, and we’re failing to execute,” said Lincoln Restler, the councilmember representing McGuinness Boulevard. “The playbook has been written. If you don’t like a project…call Ingrid, and she’ll kill it. It’s happening time and again, and it’s a problem, and it has to stop.”