The city will launch a pilot program testing neighborhood delivery “microhubs” across the five boroughs, aimed at reducing the surge of truck traffic racing to meet New Yorkers’ insatiable demand for home delivery.

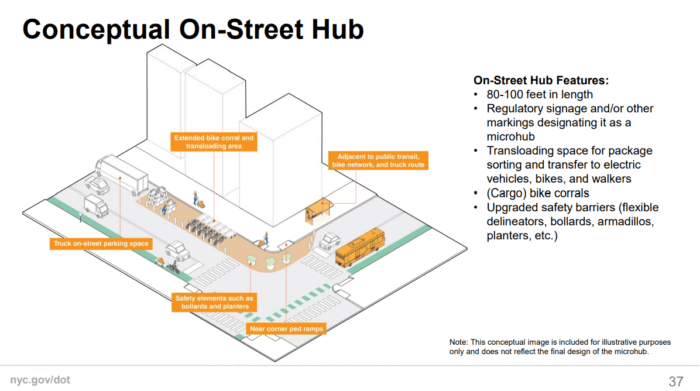

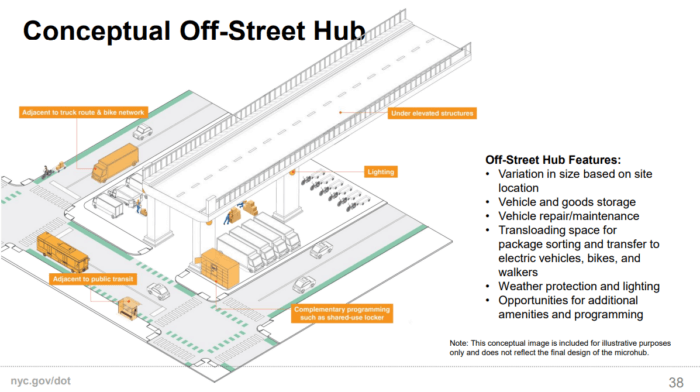

Starting this summer, the Department of Transportation says that it will build out up to 20 hubs, both curbside and off-street, where large delivery trucks can unload goods and transfer them to smaller-scale modes of transportation, such as vans, cargo bikes, or even hand-pulled carts, which would make the final leg of the journey to the customer’s door.

“New Yorkers are receiving more deliveries than ever before, and we are pursuing creative ways to make these deliveries cleaner, safer, and more efficient by reducing the number of delivery trucks on our roads,” said DOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez in a statement. “These hubs will help better organize last-mile deliveries and support small and large businesses’ economic recovery as we emerge from the pandemic.”

The move comes as the city and large corporations like Amazon face mounting criticism over the logistical process of deliveries, which sees companies set up busy warehouses, often concentrated in “environmental justice communities,” to handle record amounts of delivery demand.

DOT reports that just under half of New Yorkers are receiving at least one package delivered to their home per week, with nearly one in five receiving packages at least four times weekly

COVID-19 extensively changed the logistics of delivery: before the pandemic, about 60% of deliveries were made to commercial customers — which are typically on larger roadways more conducive to deliveries — with the rest going to residential addresses. But now about 80% of deliveries are going to residential customers, which means more truck traffic on residential streets.

The trucks dispatched from the warehouses lead to significant amounts of congestion on local streets, and by extension, air and noise pollution, both on truck routes near warehouses and on streets where deliveries end up. Trucks deliver about 90% of freight deliveries in e Big Apple, DOT says.

Environmental advocates have teamed up with elected officials to call for regulation of “last-mile” facilities through the zoning code, which would require a special permit to build new ones and prohibit their construction near schools, parks, public housing, or other last-mile warehouses. The Adams administration has not taken a position on the zoning proposals, concerned about the potential impact on the supply chain.

DOT was required to put out a “request for expressions of interest” for microhubs through a law passed by the City Council in 2021, and gathered considerable feedback from freight operators and community groups, along with tech and infrastructure companies. The feedback will be incorporated into the siting and design choices DOT makes for its initial rollout of 20 hubs, which will include both curbside spots in place of parking spaces, and larger off-street hubs underneath elevated structures like highways or subway lines.

Still up in the air is where the hubs will be located, what fees will be charged, how big they will be, how they’ll remain free of parking scofflaws, and who will run them, among other things. A DOT spokesperson clarified that for the initial rollout this summer, each hub will service just one company, though that could change in the future.

Next fall, after the first year of the pilot program, DOT will pore over the data collected on usage, demand, congestion, and other factors, and proceed to expand the pilot further. By 2026, the agency will issue a final report on how the pilot went and determine the feasibility of making it permanent.

Similar projects have yielded some positive results in other cities, the agency notes: in Seattle, a reservation system for curbside space reduced double parking by 64%. In London, Amazon’s last-mile hub replaced an underutilized parking lot and removed about 85 delivery vans from the central business district daily, reducing vehicle miles and by extension, congestion and pollution. The hubs could be hubbified further by placing other nodes directly on-site, like a delivery-focused kitchen, cold storage, or connections to marine transport.

DOT has installed over 2,000 curbside loading zones across the city since last year, the agency reported on Thursday, well above its legally-mandated requirement. The agency says that some curbs with loading zones saw double parking plummet.

Opens Plans, a nonprofit that lobbies for “livable” streets prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists over cars, gave the plan a thumbs up.

“The reality is e-commerce is ubiquitous and if we don’t design our streets to accommodate it, the current chaos will only get worse. This new approach is forward-thinking and just right for our city,” said Sara Lind, chief strategy officer at Open Plans. “Combining more loading zones with micro-mobility for the last mile will cut down on congestion, double parking, blocked bus and bike lanes, and polluting emissions. Repurposing some curb space to allow for unloading and distribution is a good use of public space.”

DOT Commissioner Rodriguez will discuss the plan before members of the City Council’s Transportation Committee on Monday, said the committee chair, Selvena Brooks-Powers of Queens. The committee will also discuss bills that would redesign the city’s truck routes and call for redesigning streets to limit truck traffic.

“New Yorkers are counting on us to create new, long-term, sustainable transportation infrastructure alternatives to allow goods to circulate in neighborhoods, while reducing the harmful environmental justice impacts of unnecessary truck traffic,” Brooks-Powers said in a statement.

The environmentalists fighting to regulate last-mile warehouses through the zoning code are cautiously optimistic about the hubs, but a spokesperson for the Last Mile Coalition, Kevin Garcia, said it would not be a silver bullet to address the myriad downstream effects of the warehouses, particularly in the neighborhoods where they’re sited.

“Microhubs can be helpful in reducing congestion and tailpipe emissions,” said Garcia, the transportation planner at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. “However, it does not address the issue of last mile warehouse siting and clustering that’s occurring in environmental justice communities.”

Environmental justice communities are those areas with disproportionately low-income and non-white populations, which have historically borne the burdens associated with polluting industries in their backyards. They are supposedly the communities that will be first in line for funds to address climate change locally.

Amazon opened its first fulfillment center on Staten Island in 2018, but since then, last-mile facilities have proliferated in the city, with about 20 throughout the five boroughs as of last year, according to researchers at the Center for Resilient Cities & Landscapes. More are in the pipeline.

A considerable proportion of those warehouses are in environmental justice communities, like Sunset Park and Red Hook in Brooklyn, Maspeth in Queens, and Hunts Point in the Bronx. Those council districts all have levels of particulate matter air pollution higher than the citywide average, according to Transportation Alternatives’ Spatial Equity tool.