MTA officials laid out their most dire warning yet about the threat of lawsuits seeking to overturn its congestion pricing program — saying the litigation puts the temporary kibosh on billions of dollars in construction priorities.

Jamie Torres-Springer, the head of the MTA’s Construction & Development arm, said Monday that the agency had hoped to ink $12 billion in construction contracts this year, as per its $51 billion 2020-24 capital plan, for work on subway station accessibility, modernizing train signals, electrifying its bus fleet, and keeping its aging system in a state of good repair.

But because of a suite of lawsuits filed by various stakeholders seeking to undo congestion pricing — which would charge a toll for motorists to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street, aiming to reduce congestion and carbon emissions — the MTA is able to commit just $2.9 billion this year, Torres-Springer said.

“This is only the bare level of investment needed to award work with federal funding, emergency work, or keeping some critical work that’s already going underway,” said Torres-Springer. “The level of investment needed to continue to improve, maintain, and expand our system, and make it more accessible, needs to be put on hold.”

The MTA is well underway installing toll gantries at points of entry to Manhattan’s central business district, and hopes to start tolling motorists by June with the aim of generating $1 billion per year in revenue. That revenue would be bonded against to raise upwards of $15 billion for mass transit projects.

But the lawsuits bring uncertainty to the specter of the MTA actually getting hold of its toll revenue, and because of that new contracts cannot be issued without a guarantee of how to pay for them.

“With any lawsuit comes risk, especially of delay, and we can’t award contracts until the funding is assured,” said Torres-Springer. “As a result, the MTA Capital Program must be placed mostly on hold. While litigation is pending, we will not be issuing any new construction contract solicitations, with very limited exceptions.”

What the delays mean

In a presentation to the MTA Board’s Capital Program Committee on Monday, Torres-Springer went into painful detail on what that would actually mean for commuters.

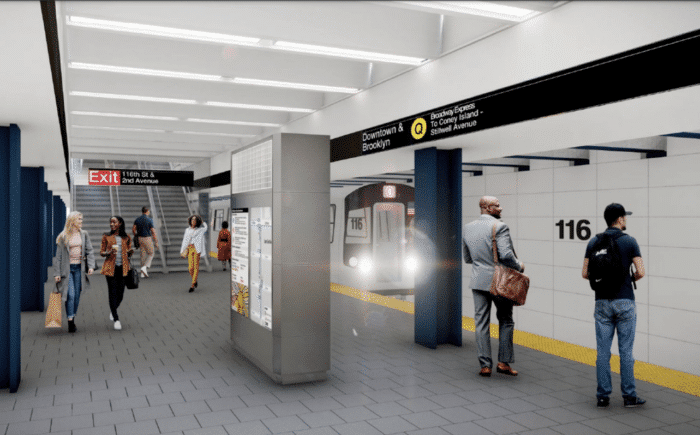

The marquee item is construction of the Second Avenue Subway. The MTA last month awarded its first contract for construction on Phase 2 of the project, which will bring the Q train to East Harlem. But the initial $182 million contract is only for relocating underground utility lines; tunneling and station construction will have to wait, Torres-Springer said.

But big-ticket system expansion isn’t the only thing facing peril. Perhaps an even bigger deal is what it means for modernizing the subway’s Great Depression-era signaling system. The MTA is in the heat of a slow and arduous process to replace those signals with modern Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC), a wireless communications array that allows rail controllers to know exactly where a train is at all times, allowing trains to run at faster speeds and shorter headways.

Only the L and 7 lines are fully equipped with CBTC, and consequently are two of the most reliable subway lines in the system. Installation is in progress on several other lines. But the MTA is unable to ink a contract for any new signal modernization projects, with Torres-Springer highlighting once-imminent plans to resignal the Fulton Line on the A/C in Brooklyn and the Sixth Avenue Line on the B/D/F/M in Manhattan. Those are now on hold.

Accessibility work at 18 stations in all five boroughs is also on hold, including at busy hubs like 59th Street-Lexington Avenue on the 4/5/6/N/R/W in Manhattan and Hoyt-Schermerhorn Streets on the A/C/G in Brooklyn.

Contracts to buy more modern trains like the R211, to replace rolling stock from the 1970s and 1980s, are in limbo, as is the purchase of 270 electric buses to replace diesel ones. Further, plans to install electric charging infrastructure at 10 bus depots are now pending.

The MTA also estimates that up to 23,000 jobs across New York State, including 5,000 outside the Big Apple, could be impacted.

Separate lawsuits against congestion pricing have been filed by the State of New Jersey, the United Federation of Teachers (joined by Staten Island Borough President Vito Fossella), and a cadre of Manhattan residents and conservative elected officials.

They accuse the MTA of conducting a shoddy environmental assessment for the first-in-the-nation congestion charge, and the federal government of negligently approving it, though the MTA contests that its 4,000-page environmental assessment was robust and comprehensive. The actions are pending in federal court.

Under the plan approved by the TMRB, most motorists would be charged a $15 base toll for entering the Manhattan central business district, with larger rates for trucks and a smaller one for motorcycles. Those driving in on already-tolled crossings would be eligible for “crossing credits,” while overnight rates would be heavily discounted to encourage off-hour deliveries.

Low-income frequent drivers would be eligible for discounts after their first ten trips in a month. Meanwhile, passengers in yellow cabs and Ubers or Lyfts would pay a surcharge on their fare. The TMRB mostly brushed off a huge laundry list of requests for exemptions to the toll, aiming to keep the base toll lower for everyone else.

Read more: Mayor Adams Appoints Joshi and Garodnick to MTA Board