The MTA Board formally voted to crystallize Gov. Kathy Hochul’s indefinite pause of congestion pricing, suspending in amber $16.5 billion of investments in modernizing the system.

The move, described by one board member as “dire” and having a “generational impact” on the transit system, comes on the heels of Hochul’s decision earlier this month to pause the toll program, which would charge $15 to drive into Lower Manhattan and was projected to reduce traffic and raise billions of dollars for mass transit improvements.

Those investments, which MTA honchos have portrayed as an opportunity to modernize a transit system that in many ways is showing its age, are now on ice for the foreseeable future.

But the language of the resolution approved by the board on Wednesday authorizes the transit agency to implement the program as soon as the pause is undone — if that ever takes place — while recognizing the agency now doesn’t have the money to make those investments, despite already spending half a billion dollars to build out the infrastructure to collect toll revenue.

“Our obligation as fiduciaries and professionals is to work with everybody, however we feel at this moment,” Lieber said at the Board meeting on Wednesday. “To try to be ready that when that financial solution that is being talked about arrives, God willing, that we will be ready to put Humpty Dumpty back together again as quickly as possible.”

In the meantime, the MTA now faces a massive hole in its capital program that keeps it from both implementing long-term plans to modernize and maintain the system — and, in increasing the cost of borrowing, could potentially lead to reductions in the operating funding used for running subway and bus service, and paying employees.

Not only will the agency lose $15 billion in direct revenue projected from the tolling scheme — which would come from bond investments against $1 billion in anticipated toll payments — but it will also lose $2 billion in federal funding for the Second Avenue Subway and another $500 million in money spent on contracts to develop the toll infrastructure.

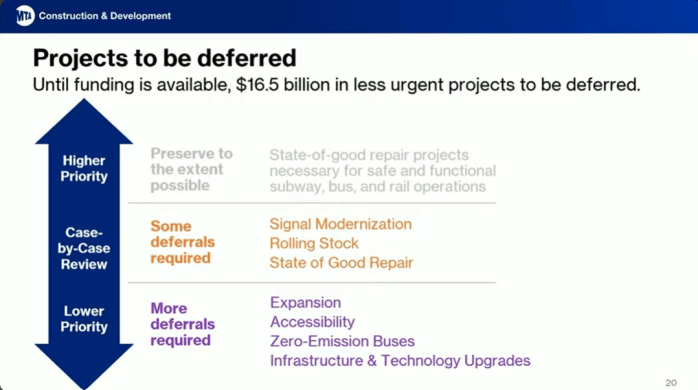

Projects left by the wayside

When $1 billion in federal funding for the Penn Station Access program — which would bring Metro-North trains to the west side of Manhattan — is accounted for, the agency faces a total funding loss of $16.5 billion, 60% of the remainder of its 2020-24 capital plan, the largest in its history.

The largest piece of funding in the gutter is $5 billion to extend the Second Avenue Subway to 125th Street, including $3 billion in local contributions that would be derived from congestion pricing and $2 billion from the feds.

“We are forced to defer this project until this unavailability of funding is resolved,” said Tim Mulligan, the MTA’s deputy chief development officer and the chosen bearer of bad news to the board. “And if it extends through the plan, it may require us to shift the project to the next capital plan.”

It includes $3 billion to replace 1930s-era train signals on the A/C line in Brooklyn and the B/D/F/M line in Manhattan with modern computer-based signal tech. Old signals are one of the primary drivers of train delays, which have increased this year.

There’s also $2 billion to make subway stations accessible for people with disabilities, which the MTA is under a federal court order to accomplish; only about 30% of stations are currently accessible, but work will be deferred at 23 stations and may be cancelled at the LIRR’s Hollis and Forest Hills stations.

There’s $1.5 billion to purchase new rolling stock like the R211 and the future R262, intended to replace the oldest train cars in the subway system, some of which date back to the administration of President Gerald Ford, as well as the LIRR’s M9A, plus $500 million to purchase 250 electric buses and install charging infrastructure at depots across the city. Another $1.5 billion was to go towards technology upgrades, like dehumidifying the cables spanning the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and upgrading public address systems at 70 train stations.

Perhaps most concerningly of all, the MTA is in triage mode to ensure the system doesn’t fall apart, work it calls “state of good repair.” Another $3 billion of less pressing projects are on the chopping block for the time being as the MTA prioritizes its most important needs, namely ensuring maintenance of tracks, elevated structures, and stations.

All of these things were projected to support some 100,000 jobs in New York State alone, according to an analysis from good government group Reinvent Albany.

“Our reality for the capital program changed dramatically 21 days ago. And we’re hopeful that resolution in some form or another is on the horizon, and hopefully in the shorter term rather than longer term,” said Mulligan. “But we have to operate the system, we have to protect the system, and we have to provide for the transition to the next capital plan.”

‘Generational impact’

The MTA Board voted to approve the pause by a 10-to-1 margin (Nassau County rep David Mack dissented because he opposes the program outright). Board members were, however, not shy to dish out how unhappy they were to take the vote.

Midori Valdivia, an appointee of Mayor Eric Adams, compared the pause to her previous work in New Jersey wherein Gov. Chris Christie canceled a long-gestating Hudson River rail tunnel project; the project has since been reborn as the Gateway Tunnel, and the holdup in addressing critical infrastructure has left New Jersey Transit and Amtrak commuters suffering from delays and poor service.

“It’s gonna have generational impact, because all transit decisions are generational,” said Valdivia. “Last week, New Jersey commuters suffered every day due to decisions made in the 2000s. So we are at a generational moment.”

The congestion pricing plan was originally approved by state legislators in the wake of 2017’s Summer of Hell, when long-term capital disinvestment exploded and service reliability slumped in a high-profile, chaotic fashion. Leaders scrambled to figure out a solution to meet the MTA’s funding needs and ultimately landed on congestion pricing, gaining approval from the Legislature in 2019.

Non-voting board member Norman Brown, the long-time voice of Metro-North riders on the tribunal, said the pause and subsequent financial uncertainty of the “old MTA” when the authority was consistently neglected, which caused various MTA projects to stagnate and their budgets to balloon in spectacular fashion.

“If you want an example of why the MTA was over budget, was behind schedule, this is it. Political interference,” said Brown. “What we have is a leadership deficit in Albany.”

Hochul to New York: We’ll figure it out

In a Wednesday afternoon statement, Hochul said that she planned to work with the Legislature to provide new streams of capital funding in next year’s state budget, and calmed her constituents that “there is no reason for New Yorkers to be concerned that any planned projects will not be delivered.”

Per Hochul — who also suggested the MTA identify opportunities for savings in its operations — her role in furnishing a financial rescue package for the MTA’s post-COVID operating budget last year should assuage fears that she won’t deliver for transit riders.

“This administration’s proven commitment to the MTA, as well as my record of delivering resources for critical priorities in the State budget, should provide the MTA with full confidence in future funding streams,” Hochul said.

Following the pause, Hochul attempted to negotiate with the Legislature first on raising the payroll mobility tax on city businesses, then committing $1 billion to the MTA from the state’s general fund, both of which were rejected by lawmakers before returning home for the summer. The governor has not produced other ideas to recoup the congestion pricing money.

Asked if he feels “full confidence in future funding streams,” chair and CEO Lieber — who repeatedly described the agency’s reaction to the pause as “business-like” and not driven by emotion — said, “I always take the governor at her word.”

“We’re expecting that there will be a solution to the $15 billion,” he noted, striking an optimistic tone.

Many who descended on MTA headquarters in Lower Manhattan on Wednesday, though, did not share that optimism.

Approximately 140 speakers signed up for public comment, which an agency spokesperson said was a record, and opponents of congestion pricing were significantly outnumbered by supporters.

The supporters included City Comptroller Brad Lander, who said earlier this month he was assembling legal and advocacy minds to craft lawsuits aimed at restoring the plan. On Wednesday, he said the likely-imminent suits will argue the pause violates the original 2019 congestion pricing statute, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the state’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, and covenants with bondholders who will likely see their investment’s rating decrease.

“The 2019 law implementing Central Business District Tolling Program remains in effect and is legally required,” said Lander. “That recognition is at the heart of the legal action that a coalition that we’ve developed with environmental legal expert Michael Gerrard is considering.”

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso said that the MTA being “disrespected and thrown to the wolves” for political considerations left New Yorkers with “arguably one of the most underfunded” transit systems on Earth.

“We cannot allow for politics to be the sole determinant of transportation policy in the greatest city in the entire world,” said Reynoso. “And that’s exactly what’s happening today.”

The Board shot down notions that the MTA could implement the program itself without the Governor’s backing, noting a federal document authorizing a “Value Pricing Pilot Program” (VPPP) is still required and needs the signature of the Governor.

Asked if the MTA had given any consideration to attempting to start the program itself, Lieber was blunt.

“We live in the real world,” said Lieber. “We’re not coming up with plans to go rogue and have a coup against the state of New York. It’s nonsense. What we’re doing is being business-like and just making sure, number one that we’re protecting ridership and service, and number two that we remain ready to implement congestion pricing when the temporary pause, as it’s been described is lifted.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/