The MTA lost nearly $700 million to fare evasion last year and should replace subway turnstiles with glass doors, an agency panel said in a long-awaited report.

The agency’s estimated losses from farebeating have climbed considerably in just a few years, from about $200-300 million before the pandemic, to $500 million last year, and now $690 million, said MTA Chair and CEO Janno Lieber on Wednesday, including $315 million on city buses and $285 million on subways.

Lieber has called the existing turnstile “too porous,” singling out the emergency exit gate he calls the “superhighway” of fare evasion where one rider propping the door open can enable scores to walk through to the platform without paying. The MTA would still have to approve any new turnstile design, but on Wednesday unveiled potential designs that all, in essence, make vaulting over the subway fare array far more difficult, if not impossible.

The recommendations came in an eagerly-anticipated report from the MTA’s “Blue Ribbon” panel on fare and toll evasion, which was originally supposed to release its findings at the end of last year but was delayed amid discussions with the city’s district attorneys.

The panel estimates that on any given day, 400,000 subway passengers do not pay the fare — about 13.5% of all riders. The numbers are even larger on buses, where about 37% of riders are estimated to skip the fare. The report quotes various unnamed subway riders who told the panel’s investigators that seeing others skip the fare was “demoralizing” and made them “feel like a chump.”

Those numbers are growing to “crisis levels,” especially on buses where ridership was free at the height of the pandemic, and the panel says the problem needs to be nipped in the bud before it becomes both financially calamitous for the MTA and culturally “entrenched” in the city’s fabric.

“We run the risk of having the culture of fare evasion becoming permanently embedded in our community, which…would wreak economic havoc on the MTA,” said Roger Maldonado, one of the blue ribbon panel’s co-chairs. “And perhaps just as importantly, would really be a lasting damage to the moral fabric of our society.”

Measuring fare evasion on buses was relatively straightforward: most MTA buses have sensors above the door automatically counting the number of people entering a bus at any given time, so those numbers were compared against the number of fares counted.

Subways were a bit trickier, and less precise: to measure the phenomenon, the MTA deploys “checkers” randomly to stations across the system about 2,400 times per year to observe unpaid entries, compare their numbers to data collected on paid fares, and use that to estimate a system-wide rate. Elsewhere in the system, fare payment data is counted against unpaid entries tallied by automated sensors like on buses, but those are only in a few stations so far.

The approach to fare evasion by the MTA and NYPD has long been criticized as punitive and overly-reliant on police enforcement and prosecution. That’s compounded by well-documented racial disparities in fare evasion enforcement: 93% of those arrested for fare evasion in the fourth quarter of last year were Black or Latino, and summonses and arrests were somewhat concentrated at stations where the rider population is low-income and largely non-white.

The panel says that going forward, police enforcement should be a last resort reserved for those caught multiple times beating the fare, a person deemed in the report as a “determined evader,” or those who bust MetroCard machines and “enable” evasion. Enforcement should be more evenly distributed at stations across the subway system instead of at stations in economically depressed areas, while on buses, the MTA should expand its civilian “Eagle” security teams that monitor jitneys to ensure payment, the report recommends.

Still, Lieber declined to commit to pushing the NYPD to “back off” on issuing summonses and arrests, which have increased dramatically under the Adams administration, and instead said he will allow the Police Department to independently evaluate the report’s findings and determine next steps.

But mustache-twirling malice is far from the only reason people jump the turnstile, the panel found. Some riders are “opportunistic” evaders who intended to pay but happen upon an opened emergency gate. Others are “frustrated” when they cannot fill up a MetroCard at a machine, and jump the turnstile or go through the emergency gate so they don’t miss their train.

Many students also skip fares as their Student MetroCards only provide a discount on weekdays during certain hours, while many other evaders simply do not have the means to pay.

To fix that, the panel recommends a host of measures beyond enforcement. Among them, there’s doubling the income thresholds for New Yorkers to qualify for Fair Fares, which the City Council has proposed for this year’s budget; expanding free rides for students to five rides per day, any day of the week; and improving signage and audio notifications warning of the penalties for fare-hopping.

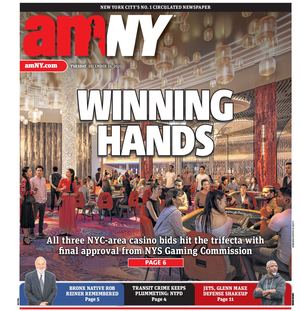

Most notably, though, the panel recommends comprehensively redesigning the fare array, replacing the easily-vaultable, thigh-high turnstile with head-height glass doors that open middle-out, and are difficult if not impossible to jump over (amNewYork Metro was unable to do so).

“These fare gates are designed to make it much, much harder for persons to evade paying the fare coming in,” said Maldonado.

Four companies presented their prototypes at Grand Central Terminal and will be subject to a competitive procurement process should the MTA decide to take the plunge and implement a new turnstile. All of the prototypes also render moot the need for an emergency exit gate, as the doors can be opened automatically in the event of an emergency.

Read more: NYC Ferry fare increase to $4 starts Monday.