For 70 years, the Hugh L. Carey (nee Brooklyn-Battery) Tunnel has provided a vital link between Lower Manhattan and the heart of Brooklyn in ways that go beyond transportation.

The twin, two-lane tubes officially turn 70 on Memorial Day, May 25, the MTA announced Sunday. Prior to its opening in 1950, plans for a Brooklyn-Battery connection predated World War II and involved the “Power Broker” responsible for shaping much of New York today, for better or worse.

Master builder Robert Moses, who led the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, planned for a Brooklyn-Battery crossing during the late 1930s. At first, Moses wanted to build a bridge connecting Lower Manhattan and Red Hook, Brooklyn, but the plan generated controversy.

According to the MTA, a number of New Yorkers opposed the bridge plan “because it would have required demolition of much of Battery Park and would have visually blocked the lower Manhattan skyline.” Then-First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was among the most vocal opponents of a Brooklyn-Battery Bridge.

As outlined in the Moses biography “The Power Broker,” written by Robert A. Caro, the bridge plan also drew concerns from the Army Corps of Engineers, who feared enemy ships could bomb the bridge and block the East River, thereby obstructing access to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

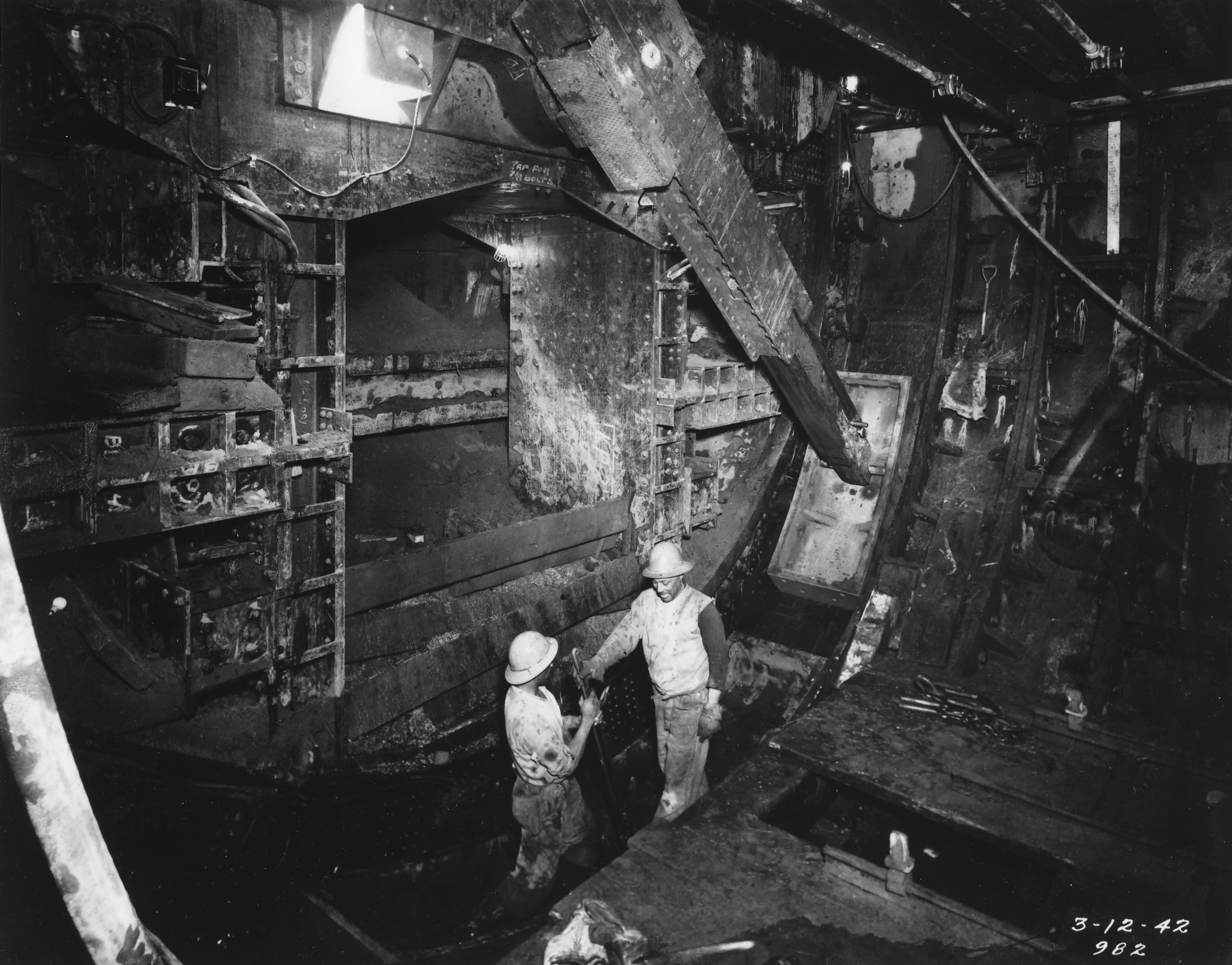

Moses ultimately abandoned the bridge plan in favor of constructing the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Construction on the tunnel began in 1940, but was ultimately halted for three years due to material shortages after the United States entered World War II on Dec. 8, 1941.

At 1.7 miles long, it’s one of the longest, continuous underwater tunnels in the world. As described in “The Power Broker,” the original walls were lined with enough ceramic tile for 4,500 bathrooms. The ventilation system was powered by fans that drove air through massive ducts “at the velocity of a Force Twelve hurricane,” and consumed every day “as much electricity as is used daily by a small city.”

The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel opened on May 25, 1950 to great fanfare, beginning with a ticker tape parade just before then-Mayor William O’Dwyer cut the ribbon on the western side of the tube at West Street in Lower Manhattan. The dignitaries then drove southbound through the tunnel to Brooklyn, where they were greeted by a cheering crowd.

At the time, a drive through the tunnel costs motorists just 35 cents; the one-way toll in 2020 is $9.50 (or $6.12 with E-ZPass). More than 57,000 vehicles travel through the tunnel today.

As important a transportation link to commuters every day, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel played an even greater role during the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. The tunnel is the closest crossing to the Twin Towers site, and emergency vehicles from Brooklyn and Staten Island used it to respond to the attacks.

One of the 343 New York City firefighters who died at the World Trade Center that morning, Firefighter Stephen Siller, famously ran through the 1.7-mile tunnel in his gear toward the Twin Towers. He had been off-duty that morning, but upon hearing about the attacks, drove to his firehouse to pick up his gear and headed to the Battery Tunnel. Because the crossing was sealed off to all traffic except emergency vehicles, he made the decision to run.

Siller’s story became the inspiration for the annual “Tunnel-to-Towers Run,” in which thousands run through the tunnel every September to raise money for Stephen Siller Tunnel-to-Towers Foundation dedicated to helping families of first responders in New York City.

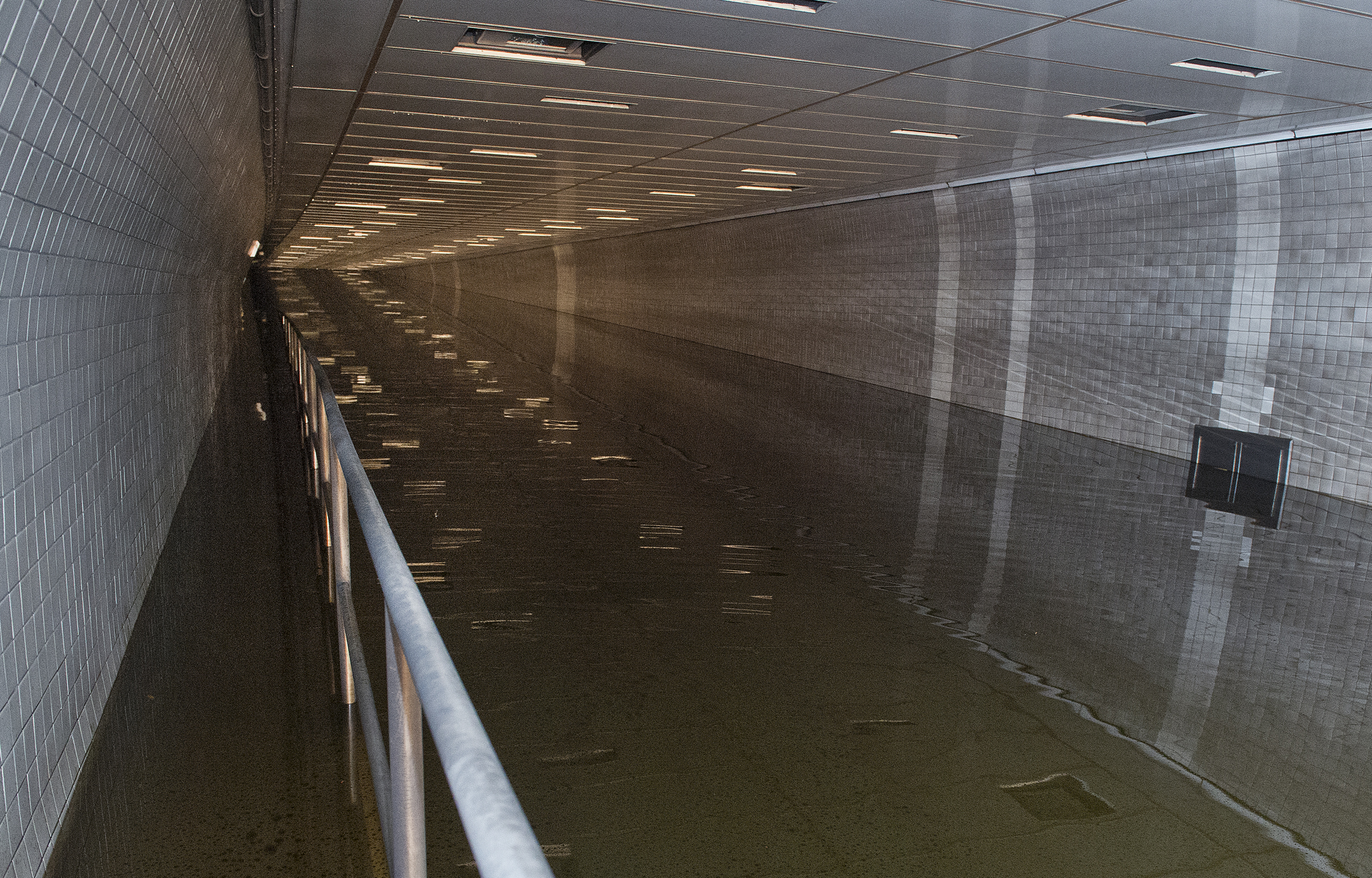

On Oct. 22, 2012, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel was renamed as the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel in honor of the late former governor of New York. One week later, the New York City area was impacted by Superstorm Sandy — and the Carey Tunnel became flooded with 60 million gallons of seawater. Nearly two-thirds of each tube became submerged, damaging vital equipment and the tubes themselves.

Within three weeks, MTA Bridges and Tunnels hustled to make temporary repairs and reopen them to traffic. In the years that followed, the authority led a massive restoration project, repairing the tunnels’ wall tiles, interior lighting, traffic control signals and pumps. Massive steel flood gates were installed at the openings in Brooklyn and Manhattan to ensure that future floods will be avoided.

The most recent change at the Carey Tunnel occurred in 2017, with the removal of manual toll booths on the Brooklyn side. They were replaced by a digital toll collection system located near the Manhattan portals.

Sources: The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, by Robert A. Caro, Vintage Books 1975; the Stephen A. Siller Tunnel-to-Towers Foundation; and the MTA.