New York was to make history on June 30 as the first American city to implement a congestion pricing program, decades in the making.

Now, just three weeks before the planned start date, history has been made of a different kind: New York is the first American city to very nearly adopt congestion pricing, before dropping it at the last minute without an equal alternative in place.

On Wednesday, Gov. Kathy Hochul indefinitely postponed the MTA’s congestion pricing plan, which would have charged $15 for most motorists to enter lower Manhattan in a bid to reduce punishing traffic in the central business district and finance the modernization of the city’s mass transit.

In a prerecorded address, Hochul said she could not allow the plan to move forward, citing concern over the toll’s impact on New Yorkers’ cost-of-living. Others, however, suspect that Hochul’s move is a political one, as Democrats seek to recover congressional seats in suburban areas particularly hostile to the toll.

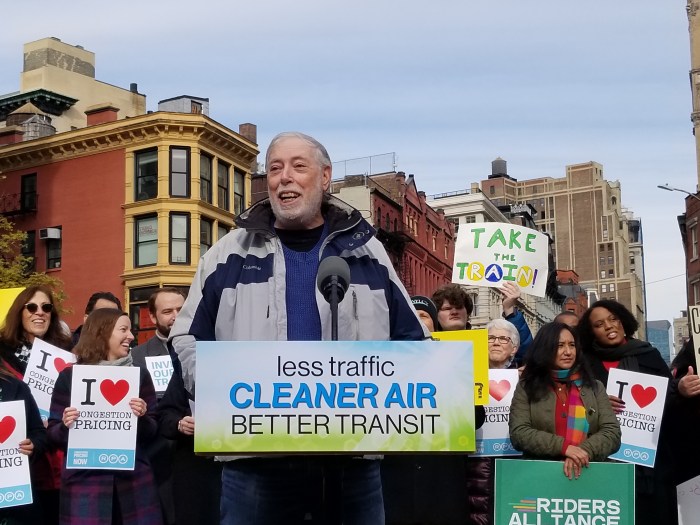

“It’s nonsense. It’s all politics,” opined Sam Schwartz, the legendary traffic engineer and former city transportation official who coined the term “gridlock.” “This is really a poor decision by the governor if she’s worried about the economy.”

Schwartz was just three weeks away from seeing his decades-long dream of pricing motor vehicle traffic come into being.

“It’s 2024, we’re 25 days from implementing it, and the governor got cold feet,” Schwartz said, describing his state of mind as “devastated” to see the plan come crashing down so close to the finish line.

A history of false starts

Speaking with amNewYork Metro, Schwartz recalled his time as an engineer at the city’s Traffic Department (now the Transportation Department) in the early 1970s under Mayor John Lindsay, when he and other engineers proposed tolling the East River and Harlem River bridges as a means of controlling traffic in Manhattan.

When Abe Beame became mayor he said the tolls would happen “over my dead body,” Schwartz recalled. Beame was sued by environmental groups who took their case all the way to the Supreme Court and won, and it appeared New York would adopt an early form of congestion pricing.

But like what occurred on Wednesday, the plan was nipped in the bud by an eleventh-hour political act: in 1977, Congress passed legislation that forbade New York City from implementing such tolls.

As he moved up the ladder to become the city’s Traffic Commissioner under Ed Koch, Schwartz tried in vain several more times to implement different versions of congestion pricing. But, also similarly to today, the plans were thwarted by numerous lawsuits and by politicians who got cold feet due to protests of the plan.

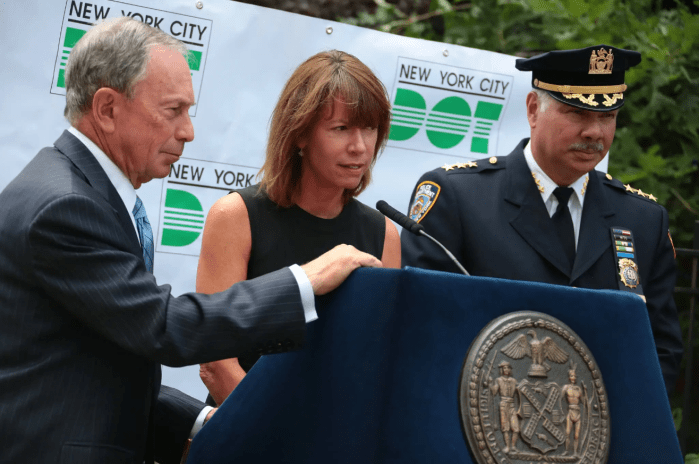

The dream was shelved for another two decades until 2007, when Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a congestion charge as part of his PlaNYC environmental proposal. By then, several world cities had adopted a congestion charge, including London, Stockholm, and Singapore; Bloomberg and his Transportation Commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, saw reducing traffic in the central business district as a venerable climate goal for the coming decades in the city.

Unlike most of Bloomberg’s PlaNYC proposals though, congestion pricing required approval by the State Legislature, and the administration could not secure that before abandoning it in 2008, running into opposition from powerful Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, both of whom later went to prison on corruption charges.

Alex Matthiessen, an environmental consultant who used to lead the nonprofit Riverkeeper, said the Bloomberg administration had done little to convince residents and pols outside of Manhattan that the plan was worthwhile.

“They did very little retail politicking, they consulted with very few rank-and-file legislators,” said Matthiessen. “And as a result, their plan was panned immediately as pro-Manhattan, and in favor of wealthy white Manhattanites.”

Matthiessen, a fierce proponent of congestion pricing, sought to change that. He founded the Move NY coalition in 2010, and ultimately teamed up with Schwartz to devise a new congestion pricing plan they felt would both achieve the aims of reducing punishing traffic while getting political support across the five boroughs and beyond.

Like Bloomberg’s plan before and the one adopted later, motorists would be tolled for driving into Manhattan south of 60th Street, but Matthiessen said the Move NY plan would appeal to suburban drivers by sharply reducing tolls on crossings entirely within the outer boroughs, and investing part of the toll revenue back into the state’s roads and bridges.

‘Summer of hell’ changed attitudes

It was stuck in the political wilderness for several years but that all changed in 2017, “the summer of hell,” the year subway service reliability plummeted in an extremely high-profile fashion due to long-term disinvestment, and New Yorkers were losing faith in their transit system. Transit advocates like the Riders Alliance were consistently hammering Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who shouldered much of the blame for the crisis, for his attempts to pass the buck, holding press conferences to explicitly tie the governor to the failures of the transit system.

Eventually, Cuomo acknowledged the need to invest in modernizing the system and jumped on the congestion pricing bandwagon, acknowledging that the policy’s “time has come.”

Cuomo empaneled a commission called “Fix NYC” which ultimately recommended a congestion charge that would funnel revenue back into mass transit. The MTA would use the $1 billion in annual proceeds to issue bonds and generate billions more for urgent construction priorities, like modernizing subway signals, making the subway wheelchair-accessible, buying electric buses, and keeping the 120-year-old transit system in a state of good repair, as well as expansion projects like the Second Avenue Subway.

Matthiessen was a vigorous supporter of the enacted plan but feels the original Move NY plan, which kicked some money back to drivers, might have assuaged some of the political rankling that followed.

“This was a good plan,” said Matthiessen. “I think it would’ve been a better plan if Cuomo had done what we did which was give some of the money to the drivers in the form of maintaining roads and bridges in the New York City area, and maybe reduce tolls on the outer borough crossings.”

Approval in 2019, of course, turned out to be just the beginning. The MTA initially intended to have the program up and running by 2021, but first needed approval from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Under the Trump administration, that agency simply bided its time for a president who has recently confirmed his distaste for the policy, and had promised to unwind if reelected this year.

The process began moving forward when Joe Biden assumed the presidency, culminating in the release of a massive 4,000-page environmental assessment comprehensively studying the policy’s impacts which won the approval of the FHWA. That was followed by a torrent of lawsuits claiming the method of environmental study used was illegal, all of which remain pending.

When Cuomo resigned amid a sexual harassment scandal, advocates initially worried Hochul, his upstate-born lieutenant, was a question mark on transit, but until Wednesday she had consistently praised the program, even explicitly rebuffing arguments from critics.

Following the FHWA’s granting approval last year, Hochul said the plan would help “millions of New Yorkers…lead happier, safer, less stressful lives.”

“She showed herself to be a person of courage, or at least we thought so,” Schwartz said.

The MTA had spent over $500 million installing the gantries to assess tolls to motorists at ports of entry to the Manhattan CBD, and had recently finished that installation. The agency was just weeks away from finally implementing the nation’s first congestion pricing program when Hochul abruptly pulled the plug on Wednesday.

Matthiessen, for one, believes Hochul’s about-face on congestion pricing is disqualifying for her likely reelection bid in 2026.

“It’s the most cowardly, craven collapse of political courage I’ve ever seen in my life. It’s extraordinary,” Matthiessen said. “She just disqualified herself for reelection in 2026. In this time of national instability and global climate chaos, we need leadership in New York, not an indecisive panderer who doesn’t know what she thinks from one day to the next.”

Schwartz, meanwhile, sees consequences emanating beyond the borders of New York’s five boroughs and 62 counties — proven to him by his experience recently at the American Public Transportation Association’s Rail Conference this week in Cleveland.

“Every city is rooting for New York City to pass congestion pricing,” said Schwartz, who now runs a traffic engineering consulting firm. “These were the transit officials of every city in the United States, Canada, and the Americas, and they were rooting for New York because if it could happen here it could happen there.”

“It’s needed now more than ever,” Schwartz continued. “We’re gonna starve our transit system yet again, we’re gonna get more people into driving yet again, and the city will become less habitable.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/