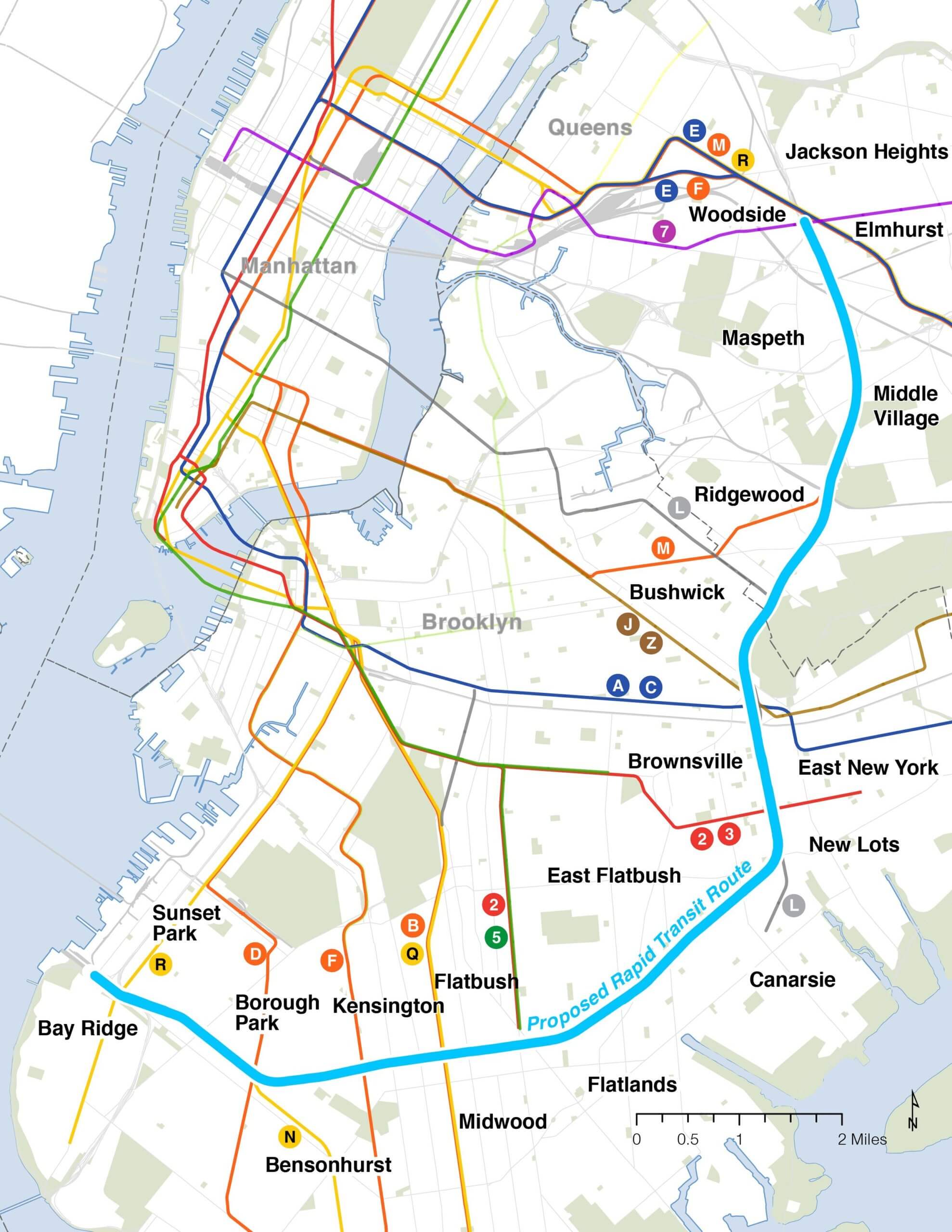

The MTA’s Interborough Express from Brooklyn to Queens could look like a blend of New York’s commuter railroads and the city’s subway train cars, should officials decide to go with the rail option for the mass transit vision, rather than buses or trolleys.

The proposal, also known as the IBX, is still in its early stages and transit officials have yet to say whether the best option will be conventional rail, light rail, or a bus rapid transit system. The former could end up resembling the London Overground in the U.K., according to MTA’s Senior Vice President for Regional Planning Michael Shiffer.

“Conventional rail is what you see on Long Island Railroad or on Metro-North,” Shiffer told a panel of subway and bus rider advocates Thursday. “In this context, the rolling stock — or the train cars, if you will — will be reconfigured to perform more like transit vehicles.”

The trains would likely have more doors than an LIRR train to accommodate frequent stops along the proposed 14-mile route passing by 17 existing subway stations, the rep said during a March 24 presentation to the New York City Transit Riders Council, an in-house volunteer body representing riders’s interests to the MTA.

“With frequent stops and frequent service we expect that people will only be riding on these trains — or buses — for relatively short periods of time to get to their connections,” he said. “So it will probably have more doors than a common commuter train and run more like a rapid transit train.”

“A good example is in London where you have London Overground, as an example of kind of a repurposed railroad that runs more like a rapid transit line,” he added.

The London Overground opened in the English capital in 2007, reusing neglected railways to expand the city’s mass transit to the suburbs and create an orbital network around the urban core.

Similarly, the IBX would run on existing freight rail right of way from the Bay Ridge-Sunset Park waterfront through central and eastern Brooklyn, and up to Jackson Heights, Queens — a 40-minute journey serving up to 88,000 weekday riders in largely working class neighborhoods of color.

IBX trains could run electrically with a third rail, like the subways do, and they would remain completely separate from the existing industrial tracks along the line, which currently serves about one-to-three trains a day.

A bus rapid transit system would run on dedicated road space and have electric buses, while light rail trams could have catenaries for part of the route and run on battery power where there’s no room for the overhead wiring, according to Shiffer.

The transit official said the Brooklyn Army Terminal at the line’s western end would be a suitable place to store IBX trains, cars, or trams.

“The Army Terminal down in Sunset Park has the significant parking area, we’ve discussed opportunities there for double-decking it, having a maintenance facility there — but the expectation is that it would be down at that end of the line,” Shiffer said.

The MTA is currently gathering public feedback on the project Governor Kathy Hochul unveiled during her State of the State address in January, as transit officials zero in on their preferred of the three transit options, before launching into an official environmental review by the end of this year or early 2023.

Following the review, the MTA plans to start designing the IBX, find a way to fund it in its next five-year capital plan starting in 2025, and pick a company for the construction contract.

MTA chief Janno Lieber previously estimated construction to take three-to-five years and for the project’s cost to be somewhere in the “single-digit billions.”

It’s not clear yet whether the IBX fares will be as steep as the LIRR or the cheaper subways and buses, but when it’s ready to hit the tracks or the road, the agency’s ticketing will run more widely on its new tap-and-go OMNY system, said another transit official.

“By the time this project would be conceivably constructed and in operation, we’re going to have all the flexibilities that OMNY will provide us,” said Will Schwartz, MTA’s deputy chief of state and local affairs. “That type of integration — if it’s a commuter railroad, or if it’s a bus rapid transit — making sure that there is that integration between the Long Island Rail Road in New York City Transit.”