The proposed Interborough Express connecting Brooklyn and Queens will move forward as a light rail project, Governor Kathy Hochul announced Tuesday in her State of the State address, bringing the dream of simplified outer borough commutes one step closer to reality but rankling some transit advocates who hoped for a more conventional rail investment.

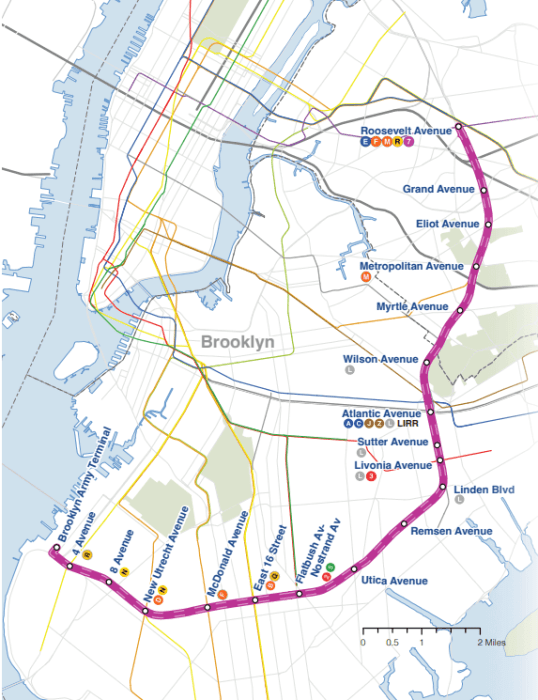

The 14-mile Interborough Express (IBX) would run from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn to Jackson Heights, Queens on the right of way currently occupied by the Bay Ridge Branch, an underutilized freight rail spur. The project, announced by the governor last year after long being dreamt of by railfans, would connect to 17 different subway lines and serve about 115,000 average weekday riders by 2045, projects the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, many of whom currently live in transit deserts or have to detour through Manhattan to get to their destination in another borough.

“Moving forward with Light Rail for the Interborough Express means better access to jobs, education and economic opportunities for some 900,000 New Yorkers in Queens and Brooklyn,” said MTA Chair Janno Lieber in a Tuesday statement. “I want to thank Governor Hochul for her leadership on this exciting project and look forward to working with stakeholders and local communities to move the proposed project forward.”

The MTA spent the past year studying the project’s feasibility, particularly whether the freight rail corridor was suitable for conventional rail, light rail, or bus rapid transit. In its final study released this month, the authority settled on light rail as the optimal path forward, requiring the least amount of expensive and time-consuming retrofitting and new construction on the corridor while also briskly moving New Yorkers where they need to go.

Per the study, light rail checked all five boxes of criteria the MTA was looking for feasibility-wise, specifically: capacity, reliability, constructability, vehicle specialization, and cost per rider.

The prospects were not quite so sunny for heavy rail, which includes high-capacity rolling stock like on subways and commuter rails. The study purports a heavy rail line on the IBX would add a nearly $3 billion premium to the project’s cost for barely any additional riders, and would actually take longer to get from one end to the other.

“The bottom line is, it was judged to be superior in terms of capacity, speed, and engineering viability,” Lieber said at an unrelated press conference Wednesday. “Principally because the size of a heavy rail vehicle could not be accommodated in some of the existing pathways, and you’d have to build a whole new tunnel.”

Light rail avoids the major engineering challenges and costly capital expenditures posed by heavy rail, the authority argues.

Key among those is an existing tunnel on the freight line underneath All Faiths Cemetery in Queens: that tunnel is too svelte for subway-like infrastructure, says the MTA, and would require costly capital expenditures to build a new tube directly underneath hundreds of people’s final resting spots.

Light rail vehicles, on the other hand, are capable of bypassing the tunnel entirely by leaving the existing right-of-way and traversing the cemetery on level ground, along Metropolitan Avenue and 69th Street for about two-thirds of a mile before returning to the Bay Ridge Branch.

That would also require capital work augmenting the streetscape to facilitate the trains, and potential opposition from community groups, but the MTA deems those challenges more workable than a whole new tunnel.

Overall, the projected cost of the light rail project as of now is $5.5 billion — a “very, very moderate” sum, according to MTA construction chief Jamie Torres-Springer, who said the price tag translates to a relatively low $48,000 cost per rider as compared to the heavy rail option and light rail systems in other American cities. Riders could expect 5-minute peak and 10-minute off-peak headways on the line.

The agency hopes to kickstart environmental review this year so that actual construction can be covered under the MTA’s 2025-29 capital plan.

Still, the decision rankled at least some transit advocates. The Tri-State Transportation Campaign, for one, said that light rail would not allow the project to be as transformational as it could be as a subway or commuter rail line.

“It’s time to break free from the fragmented, patchwork transit system that leaves too many people stranded and disconnected,” said Renae Reynolds, executive director of TSTC. “Our region deserves a seamless transit network that works for everyone. The Governor and MTA must prioritize the needs of all riders and the whole region, and invest in a system that will bring us into the 21st Century.”

The current proposal is already a down-scaling from the dream proposal of years past by the Regional Plan Association, which called for the new train line to extend up into the Bronx. The Boogie-Down section went on the chopping block for engineering reasons: the Hell Gate Bridge between Queens and Randalls Island is already used by Amtrak trains and will soon carry Metro North trains heading to Penn Station, and the bridge is not believed to be capable of carrying additional train traffic with shorter headways.

Nevertheless, the IBX would arguably be the biggest and most ambitious expansion of rapid transit in the Big Apple in decades, connecting transit deserts like East Flatbush, Flatlands, and Middle Village to the rail system. And it would reorient transit to more closely hue to today’s commuting patterns, which increasingly see travel between two outer boroughs or within one borough, instead of from outer boroughs to Manhattan, saving time and headaches.