The MTA will convene a panel to study allowing New Yorkers to bring unfolded strollers on city buses, after parents made repeated demands that the agency relax its policy on baby carriages.

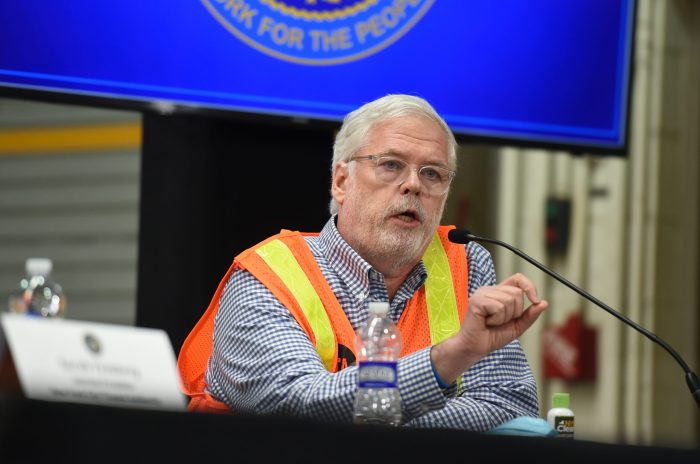

The group will look at how to accommodate the strollers while not blocking people with disabilities, said New York City Transit interim President Craig Cipriano during a Monday meeting.

“We heard our customers’ feedback, both the need for enhanced access on buses from caregivers with strollers and from disability advocates who are concerned with the potential conflicts and impact to their access,” Cipriano said during MTA’s monthly board committee meetings on March 28.

“To address this, we’re going to convene an advisory group composed of bus operators, disability advocates and caregivers who use strollers,” he said.

The body of advisors will assess the issue and report back to Cipriano and the New York City Transit committee with their findings once their work is done, the subways and buses chief added.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses currently have a rule banning unfolded strollers on board, due to concerns about safety while riding and blocking the way for other passengers.

Parents at last month’s board meetings detailed their struggles of collapsing the carriages while at the same time holding a baby or moving around shopping bags, calling it a “total nightmare.”

A Brooklyn dad in 2017 launched an online petition that has since gathered almost 62,000 supporters calling on MTA to relax its stroller rules.

In other cities like Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Dallas, local transit allows open strollers on buses as long as there’s enough room for other passengers and depending on the cart’s size.

Cipriano’s incoming replacement at the top of NYCT and former Massachusetts Transportation Secretary Rich Davey, who is slated to take over the job managing New York City’s buses and subways on May 2, has said he regretted instituting a stroller ban on buses in Boston during his tenure.

“I wish I didn’t propose banning strollers from buses. That had to be the dumbest idea I floated, but that was mine,” Davey said in 2014.

At Monday’s transit meeting, both parents and disability rights activists said the agency should figure out a way to allow everyone a comfortable trip.

“We’re asking for a reasonable request. We want to be third in line to the disabled and the elderly. It’s not us versus them and we should not be pitted against each other for space,” said Upper East Side mom Danielle Avissar.

Conflict between drivers, parents, and wheelchair users “would happen unquestionably,” said Joe Rappaport of the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled, unless the panel figures out a clear way to deal with the issue.

“I want to make it clear that no one opposes making it easier for parents and other caretakers to ride buses and subways,” Rappaport said. “We really look forward to sitting down with you, with parents, with drivers, and the union, and other disability groups, to come up with a plan that actually works and doesn’t deprive wheelchair users of a federally-mandated right.”