The overwhelming majority of subway emergency brake activations, like the one that precipitated last week’s 1 train derailment, are bogus, according to the MTA’s top executive.

Just 30 of the more than 1,700 emergency brake events recorded last year were for legitimate emergencies, MTA Chair and CEO Janno Lieber said on WNYC radio on Monday.

For the most part, the brakes are being activated by vandals, Lieber noted. That problem came to the fore last Thursday afternoon when vandals pulled the brake on a 1 train at 79th Street on the Upper West Side, forcing the train out of service and forcing other 1 trains to use the express tracks shared by the 2 and 3 lines.

As the out-of-service train trudged its way to a yard in the Bronx, it proceeded against a red signal as another 1 train with hundreds of riders — which had a green signal — switched from the express to local tracks near 96th Street, causing both trains to collide and derail and injuring 26 passengers.

“Most of them are vandalism,” Lieber told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer. “And the result is, when they can’t reset the brakes, which is what happened in the case of this passenger train that had the collision, it disrupts everybody.”

Indeed, the derailment caused two days of major disruptions for commuters on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, shutting down the 1, 2, and 3 lines for more than two days until it was fully restored on Saturday night. Crews had to carefully perch the wayward train cars back onto the rails and repair the tunnel’s tracks and third rail, which powers subway trains with electric current, as well as conduct safety inspections.

A disruptive yank

Emergency brakes are located in every subway car as well as in the operator and conductor cabs. On older cars, the brakes can be activated by pulling down on a cord, while newer cars require people to open up a compartment and pull down like a fire alarm.

Activating the brakes causes trains to stop abruptly — a “professional, immediate halt, right away,” Lieber noted — and the MTA advises riders not to pull it even in most emergencies, such as fires, crimes in progress, or medical episodes.

That’s because stopping a train requires crews to investigate the incident and relay information to central dispatchers, which can cause ripple effects throughout the system. Brakes must also be “reset” after being investigated, Lieber said, before trains can move forward again.

Instead, in most emergencies, riders are directed to inform train crews of the situation using emergency intercoms located in train cars. Only if “the train’s continued movement presents an immediate danger to people,” which may require evacuation, should a rider activate the emergency brake, the MTA advises.

Pulling the emergency brake without a genuine emergency is against the MTA’s rules of conduct, being deemed as “interference with movement,” and comes with a $100 fine.

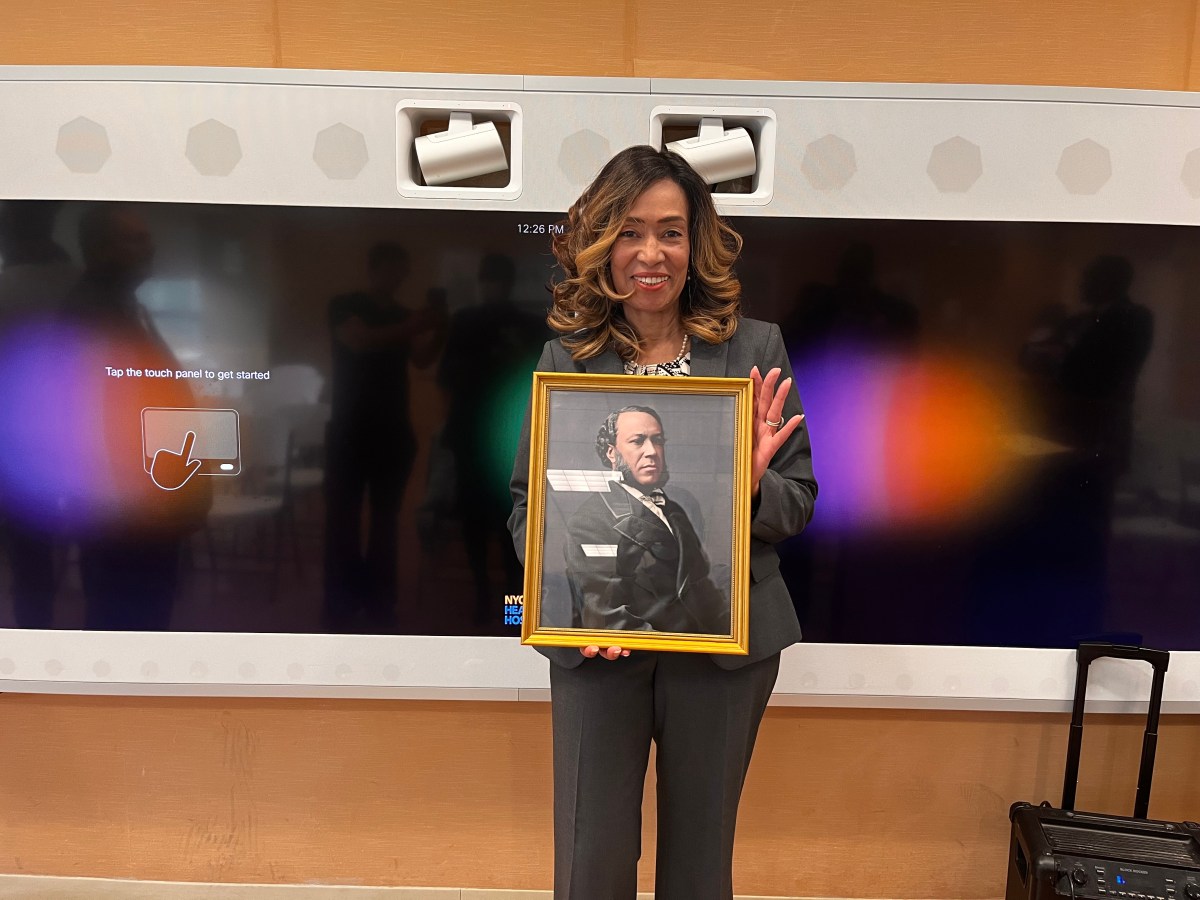

Back in 2019, a scofflaw disrupted thousands of people’s commutes by intentionally pulling emergency brakes on numerous trains. The man arrested for the misdeeds, Isaiah Thompson, faced a laundry list of other accusations of crime within the subway system, including pushing someone in front of a train, slashing someone, exposing himself, and subway surfing.

Last week’s derailment is still under investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board. The person or persons who vandalized the 1 train slipped away without being caught and are still on the lam.

The MTA is in the process of equipping all train cars with surveillance cameras, which officials hope can allow for the quick capture of scofflaws in the future.

“If we have cameras in cars, inside the cars, like we are putting in, we’re gonna be able to get those people,” said Lieber. “Just like we get everybody who commits major crimes on the platforms, in the mezzanines, and elsewhere in the system. So I’m really optimistic that we’re gonna be able to crack down on that form of vandalism.”

Read more: Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 Construction Starts Soon