The MTA will provide tolling discounts to some low-income drivers, cap daily tolls for taxis, and invest more than $200 million to mitigate localized increases in traffic and air pollution under an agreement with the federal government allowing it to implement congestion pricing, the agency announced on Friday.

The agency’s newly-released final environmental assessment addresses various problems the feds had with its draft version released last August, with those efforts crucial to the Federal Highway Administration’s effectively giving the program — which will assess tolls on vehicles entering Manhattan below 60th Street and send the revenue to the MTA to bolster its aging infrastructure — the green light last week.

Those include:

- Discounting overnight tolls between midnight and 4 a.m. by at least 50% below peak commuting hour levels, intended to encourage trucks to deliver freight in the wee hours of the night when traffic is lighter.

- Providing a 25% discount to “low-income frequent drivers” — those making less than $50,000 per year or who receive federal benefits, who frequently drive into Manhattan because they have little choice due to their work (this doesn’t apply to overnight trips).

- Capping toll issuances for taxi and for-hire vehicle drivers to once per day.

- Investing in environmental mitigation for the communities expected to see increased traffic, particularly in the Bronx, like electrifying truck fleets and installing air filtration systems in schools.

Toll rates have not been finalized, but still fall under the same ranges as in the draft assessment under several scenarios: $9-23 for cars, motorcycles, and commercial vans; $12-65 for small trucks; and $12-82 for large trucks. Final tolling rates and policies, which could fall anywhere within those ranges, will be determined by the Traffic Mobility Review Board, which was empaneled last year by the MTA, after which the program is expected to finally be implemented sometime in 2024.

New York’s program would be the first example of congestion pricing used in the United States. The MTA estimates it could bring in between $1-1.5 billion per year in toll revenue, which would allow the agency to raise $15 billion in capital through the issuance of bonds. The funds would be used to spend on infrastructure, like replacing its Great Depression-era train signals and making the subway system accessible for people with disabilities.

The MTA also estimates vehicle traffic in the CBD to decrease by up to 20%, reducing both the congestion on Manhattan’s roads and overall carbon emissions from vehicles.

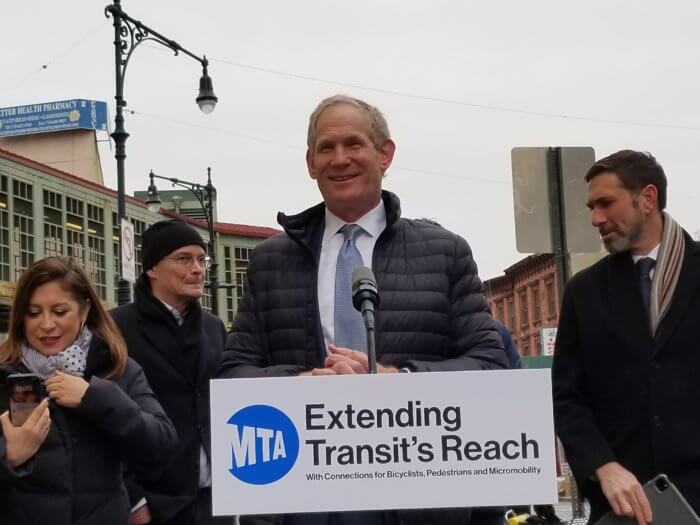

“This is a big milestone for New York. We are moving forward with the plan for congestion pricing, which is really about four things: less traffic, cleaner air, safer streets, and better transit,” MTA Chair and CEO Janno Lieber told reporters on Thursday. “We want that for New York that’s why we’re thrilled that the federal government has moved us forward to what would appear to be the final stages of this complex environmental review process.”

The MTA insists that by getting people out of cars and onto mass transit, the entire New York metropolitan region will benefit from reduced carbon emissions and air pollution. Depending on what is ultimately implemented, the MTA estimates car traffic in the Manhattan CBD will decrease by 5-11% and truck traffic will decline between 21-81%.

The agency doesn’t expect anywhere in the city or upstate to see an increase in vehicle miles traveled due to tolling; however, Long Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut could see VMT increase by less than 0.2%, which is not considered a “significant impact.”

But the authority concedes that some localized areas could experience negative ramifications from the plan as traffic is diverted to those places instead of the CBD. About 50% of so-called “environmental justice census tracts” near highways could experience increased truck traffic as a result of congestion pricing, and addressing those issues was integral to getting approval from the feds.

Key among these is the corridor around the Cross Bronx Expressway, an important stretch for the city’s supply chain. The MTA will spend $15 million to electrify up to 1,000 diesel-spewing refrigeration trucks at the Hunts Point Produce Market — which supplies 60% of the city’s fresh produce — and $20 million to build out seven electric truck charging stations, for instance.

Additionally, $25 million will go toward renovating parks and greenspaces in environmental justice communities and $10 million will go toward roadside vegetation. Another $10 million will be spent on air filtration systems at schools near highways, and $20 million will fund an “Asthma Case Management Program” at Bronx schools. Another $5 million of toll revenue will fund an expansion of the city’s off-hours delivery program, while $20 million will help expand the city’s Clean Trucks incentive program with 500 new lorries.

Overall, $155 million will be spent on environmental mitigation measures, with another $5 million for monitoring and $47.5 million for low-income discounts.

“Any congestion pricing plan must recognize and respect the unique environmental and public health needs of the Bronx,” said Bronx Congress Member Ritchie Torres, who lobbied for the measures. “I’m proud to have successfully secured $155 million over five years in new investments to significantly reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.”

Mass transit already makes up the considerable bulk of trips into Manhattan’s CBD: 75% of the 7.7 million people entering Manhattan below 60th Street do so by mass transit, with 24% by car and 1% by other means. Of those, only about 16,000 people — 0.2% — are “low-income frequent drivers” who would qualify for the toll discounts, said Lieber. Just under 80% of low-income commuters arrive in Manhattan on mass transit.

The approval of the final environmental review kicks off another 30 days of public comment, after which the MTA hopes the feds will issue a “Finding of No Significant Impact,” or FONSI. If that occurs, the Traffic Mobility Review Board will begin deliberating on final toll rates.

Congestion pricing was first approved by Albany in 2019, with the MTA hoping that the program would be up and running by 2021. However, the agency faced stiff resistance from the Trump administration. When the keys to the White House changed hands, the Biden administration allowed the environmental review process to move forward, although the process has been slow owing to the breadth and complexity of the project.

The proposal has not been without controversy. Over 22,000 people formally lodged comments with the agency, many of them negative and focused on a vast array of grievances. Many in the suburbs have expressed outrage at not being able to drive into Manhattan for free, and some, like New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, have suggested filing lawsuits to prevent its implementation.

On Friday, rideshare company Lyft said in a statement that the cap on FHV tolls would be a “logistical nightmare” and said the cost would be borne by drivers. FHVs already pay a $2.75 fee to the MTA to operate below 96th Street in Manhattan.

“There is no way for companies to know if a driver has already passed through the congestion zone by giving a ride on another platform or ride service. It would fall on the driver’s shoulders to pay the fee,” Lyft said in a statement. “Instead of burdening drivers further, the MTA should acknowledge that our industry has for years already paid them a congestion pricing fee and focus on ensuring the program is funded fairly across all who use our roadways.”

Critics argue that the environmental assessment was not thorough enough since the MTA was permitted to undergo a short review—rather than a full environmental impact statement, which would take several years. But on Thursday, Lieber contended that the 4,000 pages of review constituted perhaps the most extensive research into the environmental impacts of public policy in New York’s history.

“There will probably be some lawsuits, but this has been the most extensive review process maybe in history, certainly for a project of this kind,” Lieber told reporters. “We studied the intersections all the way down almost to Philadelphia, we studied the air quality impacts, we studied all the social justice impacts. I’m confident that this 4,000-page document will stand up to scrutiny.”

This story was updated at 12:15 pm on May 12 with comment from Lyft.