New Yorkers with disabilities are locked in a battle with the MTA over gaps between trains and platforms at its subway stations which can keep disabled riders off trains even as the MTA spends billions on other accessibility upgrades.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), vertical gaps between platforms and trains are not to exceed 2 inches under any circumstances, while horizontal gaps cannot exceed 4 inches; regulations are even more stringent under New York City’s Human Rights Law.

But the 120-year-old subway system was built long before any consideration was given to disabled riders, and contains many gaps that go well beyond what’s prescribed by law.

At 14th Street-Union Square on the 4/5/6 line, the curved platform creates a gap so wide that a small section moves closer to the train once it stops, making a loud clang in the process.

But Union Square is far from the only stop with a large gap, many of which are left uncorrected.

B trains at 59th Street-Columbus Circle have a horizontal gap of up to 7 inches in width.

At Times Square-42nd Street, 7 trains have not only a 5-inch horizontal gap, but a 5-inch vertical gap as well.

Minding the gap

“I’ve had the train arrive and I look down and suddenly realize the gap is larger than I thought it would be, and that for me is an issue. Because they only stop for a second,” said Upper West Sider Jacqueline Goldenberg, who just turned 80 and has bad knees and worse eyesight. “I plan my trips, I’m more afraid of certain stations.”

Goldenberg and other New Yorkers with disabilities filed a lawsuit against the MTA in 2022 alleging the transit agency was violating the city’s Human Rights Law, intent on having the sizable gaps declared illegal and ordering the transit agency to fix them with haste. The plaintiffs recently won a victory in court that kept on New York City, which technically owns the subway but leases it to the MTA, as a defendant after City Hall attempted to wiggle out.

Goldenberg has never fallen through a subway gap, but every time she commutes by train she says she fears falling through it. “I haven’t specifically fallen into a gap, but I have had the feeling as I was exiting that I certainly could,” she said. “There’s suspense.”

Another plaintiff was once trapped on a subway train when her power wheelchair couldn’t get over the gap. Still another, who’s blind, relies on swinging her cane at the train to determine the gap and safely board the train.

The plaintiffs, represented by New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, say the MTA has workable, cost-efficient solutions to address the problem but is failing to do so. For example, city buses have retractable folding “bridges” that allow people with disabilities to safely board from the sidewalk, as do trains operated by New Jersey Transit.

Disability access remains one of the MTA’s thorniest issues. Just 30% of stations are considered accessible under the auspices of the ADA, which passed Congress 34 years ago, and New York is well behind peer cities in making its system fully accessible even after accelerating accessibility work in its most recent capital plan.

“While we won’t comment on this litigation, MTA accessibility upgrade projects have been awarded at five times the pace of previous administrations, with 38 additional stations currently in the pipeline, consistent with our priority to provide access to transit for all New Yorkers,” said MTA spokesperson Michael Cortez in a statement.

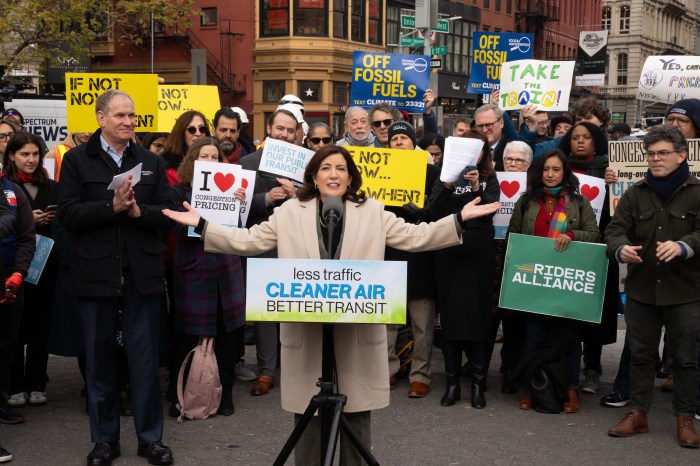

In 2022, the MTA reached a settlement wherein it agreed to make 95% of subway stations accessible by 2055, but even that hefty timeline is in question now after the pause on congestion pricing yanked away funding for dozens of accessibility projects.

It’s all part of a pattern of policy and design choices that Goldenberg feels shut her and other older New Yorkers out of their city.

“The message to people like me is be invisible,” said Goldenberg, who noted she doesn’t see a lot of other older New Yorkers when she rides the train. “When I see the subways, I see a sign that says you are not welcome here.”