Riders of the heavily-subsidized NYC Ferry system became even wealthier and whiter during the pandemic, according to city statistics.

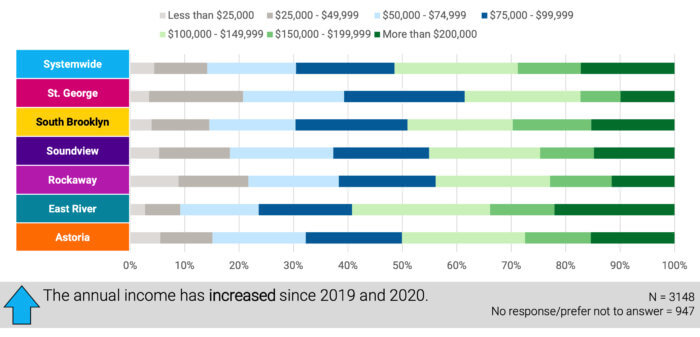

Annual surveys by the Economic Development Corporation — which oversees the waterborne transit system — show that in 2021 the average income of passengers jumped to six figures at $100,000-$149,999, compared to $75,000–$99,999 for both 2020 and 2019.

In a system long criticized for serving largely the well-off and white living along the Big Apple’s waterfront, a mere 32% of passengers identified as non-white or multiracial last year, declining slightly from 34% in 2020, and 36% in 2019.

The city questionnaire also found that more out-of-towners are coming back to the ferries, as tourism began recovering from a COVID slump in 2021.

Last year 88% of ferry riders were residents of the Five Boroughs, compared to an all-time high of 95% during 2020, and 86% in 2019.

EDC’s most recent report gathered data from 4,100 people in early October. The figures appear to have been published in December, according to its hyperlink address, but have not previously been reported.

The chairperson of the City Council’s Transportation Committee lamented that the ferry system has continued to leave out needier New Yorkers, despite footing the bill for the service through their tax dollars.

“The communities that are in need, that are a part of transit deserts, and that have lower household incomes, those are not the communities, unfortunately, that have the pleasure of having a ferry system,” Queens Councilmember Selvena Brooks-Powers told amNewYork Metro. “We need to make sure that it’s not leaving out a community that could greatly benefit from the access and from it being subsidized, quite honestly.”

The 2021 study notes that the higher incomes last year were “in line” with data the city collected in 2017 and early 2018, however that was before EDC expanded its ferry service area to more blue collar parts of the city like Soundview in the Bronx, which opened a landing in August 2018.

On that route, the majority of passengers make less than $100,000 a year and ridership has the largest share of people of color compared to other circuits — which is still less than half, according to graphics in the report.

The most popular route remains the East River service, transporting locals living in some of the wealthiest parts of Brooklyn like Williamsburg and Dumbo, and which also had the largest share of six-figure earners.

The ferry stats buck trends found in the subways and buses, which are run by the state’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

More straphangers stayed on the rails and the roads in poorer sections of the city like the Bronx, compared to wealthier Manhattan during the first year of the pandemic, a report by former Comptroller Scott Stringer detailed last year.

Stringer at the time chalked the discrepancy up to people at white-collar jobs staying remote while frontline workers kept commuting throughout the health crisis.

Buses — whose ridership tends to be more lower income and from communities of color than the subways — have consistently carried a higher percentage of their pre-pandemic passenger levels than trains.

Critics have for years slammed the steep public cost to keep the ferry service afloat, with EDC subsidizing each $2.75 trip with about $9.

The system, which is overseen by EDC but operated by private company Hornblower, was a pet project of former Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Hizzoner pitched it as a boon for poorer New Yorkers without good transit access, even though officials knew it was primarily being used by the rich from the get-go, the New York Post revealed in early 2020.

De Blasio supplied a $23 million infusion of cash shortly before he left office, and EDC voted to start churning through city tax dollars for the first time to fund the service, The City reported.

Previously, the quasi-public city nonprofit diverted proceeds from its real estate portfolio to pay for the ferries.

During his last year in office, de Blasio opened another stop in St. George on Staten Island — right next to the iconic and free Staten Island Ferry — and another one in Throggs Neck in the Bronx.

EDC postponed the opening of one more new landing in Coney Island, Brooklyn, until later this year.

The City Council is pushing to fund more expansions of the ferry system in the upcoming budget.

The Council wrote in its official response to Mayor Eric Adams’s preliminary spending proposal Friday that more stops should come to the boroughs outside of Manhattan, arguing that it will give more New Yorkers access to transit while “stabilizing” the current system as ridership recovers from the pandemic.

Brooks-Powers said she has spoken to her colleagues representing parts of southern Brooklyn and the South Bronx that could benefit from a stop, as well as her own southeast Queens.

“What we’ve seen in the ferry service to date is the potential that it holds, the potential to bring people from one place to the next to create an alternative mode of transportation in an affordable way,” she said. “The challenge that we have with it is that it is not connecting the New Yorkers who are most in need financially, and so that’s where the shift needs to happen.”

Ferry passenger numbers have always been a mere fraction of the city’s subways and buses.

The latest counts from the final three months of 2021 registered 11,688 average weekday riders, 82.5% of same time in 2019 and 12,984 on weekends, which was actually 18% above pre-COVID figures.

The subways carried an average 2.66 million a day during the last quarter of 2021 and 1.2 million on buses, about 57% and 63% of pre-pandemic figures, an amNewYork Metro analysis of MTA data found.

An EDC spokesperson said that the ferry remains an affordable transit option for all New Yorkers.

“As ridership recovers from the pandemic, NYC Ferry continues to offer affordable and accessible transit for all New Yorkers – for the same fare as a subway ride,” said Mary Mueller in a statement. “We proudly serve 25 landings across all five boroughs and will stay focused on running a system that is helping to power the city’s recovery.”