A city program intended to hold repeat reckless drivers accountable for their actions quietly expired last week, with little to show for what had seemed a promising initiative to curb dangerous driving.

The Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program (DVAP) was enacted in 2020 as a means of educating reckless motorists on the consequences of their actions, or else take away their vehicle. As written, DVAP required drivers who racked up at least 5 camera-issued red light tickets or 15 speed camera tickets in one year to enroll in a driver “accountability” course intended to demonstrate the potentially fatal consequences of their actions.

Drivers could contest the requirement before the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH); if a judge there agreed with the Department of Transportation (DOT), but the driver still failed to enroll in the course, their vehicle could be impounded.

The bill was originally sponsored by then-Brooklyn City Council Member Brad Lander to assign accountability to people racking up scores of camera-issued tickets. Unlike those written by a police officer, camera-issued tickets don’t add points to one’s license, so drivers are free to rack up as many as they want provided they pay the associated $50 fine.

The program expired on Thursday, Oct. 26, and in a report from his office, now City Comptroller Lander said the city had “failed to implement the program as designed” across two mayoral administrations.

Enacted just before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the city implemented the program a year later than intended, Lander said, didn’t take advantage of existing courses offered by the nonprofit Center for Justice Innovation, and “did not follow through on the legislated scale or key elements.”

Tens of thousands of drivers were eligible for the one-time, 90-minute course, Lander said, and sponsors intended for about 5,000 drivers per year to cycle through it. But in the program’s two-and-a-half-year history, DOT only informed 1,605 people that they had to take the course, according to the Comptroller.

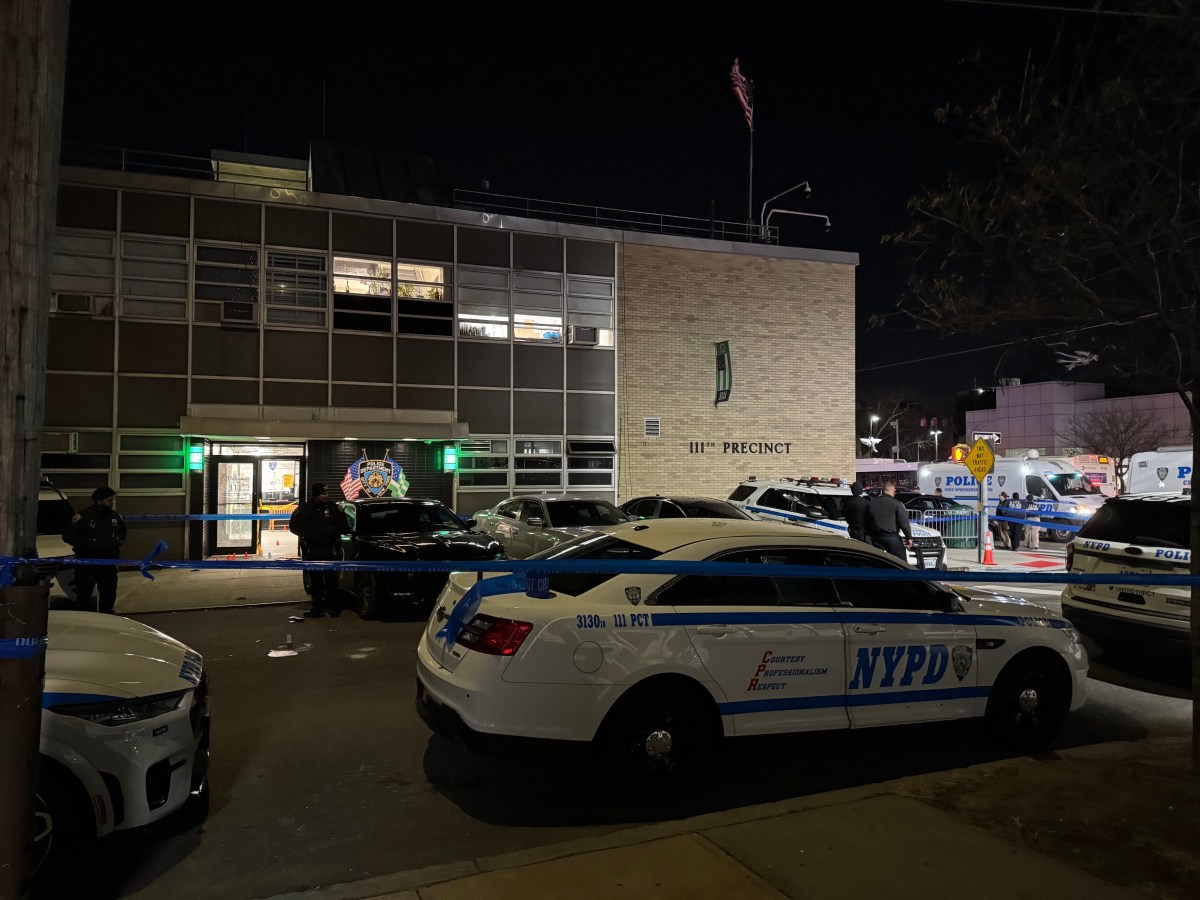

Nearly half of those, about 720 drivers, simply ignored the warning and refused to take the course. DOT would obtain 159 warrants to seize scofflaws’ vehicles, each of which took months to acquire; at the program’s expiration, just 12 vehicles had been impounded by the city under authorization by DVAP, which Lander attributed to staffing constraints at DOT and OATH.

“Even where repeat reckless drivers cause serious injuries or fatalities, they are rarely prosecuted,” Lander said in the report. “The lack of consequences for drivers known to engage in reckless behaviors remains a serious gap in the City and State’s traffic safety laws.”

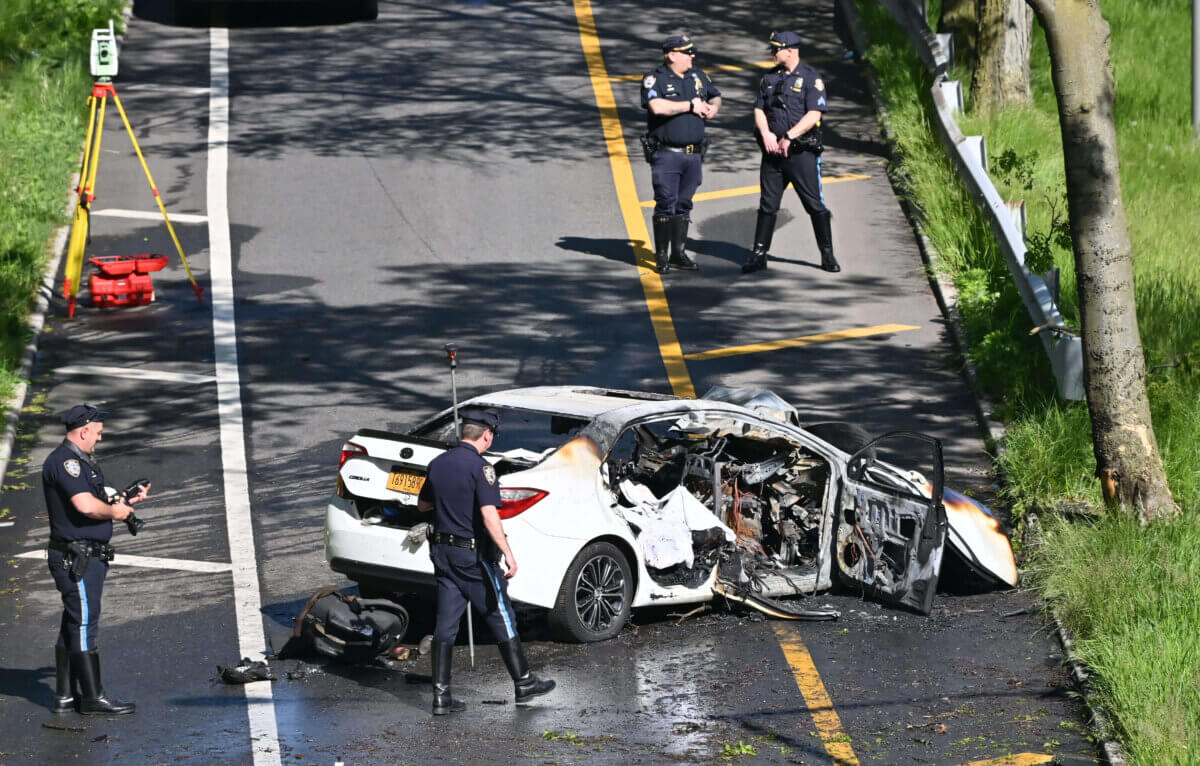

Indeed, lack of accountability for repeat reckless drivers can have deadly consequences. In September 2021, Tyrik Mott was behind the wheel of a Honda with Pennsylvania plates, speeding in the wrong direction in Brooklyn, when he smashed into another car at Gates and Vanderbilt avenues, causing that car to careen into a couple walking their 3-month-old baby in a stroller. The baby, Apolline Mong-Guillemin, died at the hospital, while her parents both suffered debilitating injuries.

Mott, who was sentenced to nine years in prison this June, had racked up an astounding 160 camera-issued tickets on his Honda in four years, many unpaid, making him eligible for the DVAP course and arguably the poster child for the program. In fact, he had previously taken the driver accountability class, but had apparently continued to drive with reckless abandon. He had been arrested earlier in the year for driving without a license, but a judge let him off the hook upon a promise of good behavior.

Despite his reckless habits, Mott never faced the specter of his car being impounded prior to killing Baby Apolline. Last July, Apolline’s parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city, alleging the government bore culpability for the tragedy for failing to design streets safely and, crucially, failing to enforce DVAP. Lawyers for the city later filed motions blaming Apolline’s parents for her death, contending they should have known the risks of walking on a New York City sidewalk. The case is still pending in Brooklyn Supreme Court.

On the very day DVAP expired, not too far from what’s now the Apolline’s Garden pedestrian plaza, another child, 7-year-old Kamei Hughes was crossing the street on a scooter with his mom when he was fatally struck by the driver of an NYPD tow truck. The driver, Stephanie Sharp, was arrested and charged with failure to yield to a pedestrian and failure to exercise due care.

In its evaluation of the program released last month, DOT recommended that DVAP not be reauthorized following expiration, for a litany of reasons. The agency disputes Lander’s contention that it failed to implement it properly, asserting instead that it was hampered by external factors largely out of the city’s control.

Motor vehicle licensing and registration is controlled by the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles, not the city DOT, and so it was a “complex and lengthy process” for the city to impound vehicles for camera-issued violations. Those eligible for the course proved hard to track down for a variety of reasons, like getting a new car or swapping their plates, while those who did take the course could quickly get back behind the wheel, like Mott. Administering the course was also labor-intensive and costly, at $1,000 per participant, according to DOT.

Program participants appear to have accumulated significantly fewer tickets after completing the course, according to the report, but so did everyone else in the period between 2020 and 2023. That coincided with the introduction of 24-hour camera enforcement and the wider proliferation of them across the city.

Unlike DOT, Lander endorsed reauthorizing and expanding the program. He said the course should be a multi-day, comprehensive affair, and that vehicle impoundment warrants should be easier and take less time to acquire.

In Albany, the Comptroller endorsed passing bills to automatically suspend the licenses of drivers with high numbers of camera violations and require the installation of speed-limiting devices in reckless drivers’ vehicles. DOT press secretary Barone said the agency supports both bills.

“Our comprehensive evaluation of the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program, which included a rigorous analysis of the driving records of hundreds of participants, found that the program — while well-intentioned — was ineffective at meaningfully reducing unsafe driving,” said Barone. “We welcome the Comptroller’s partnership in advocating for new state laws to get dangerous drivers off the road and plan to do other targeted driver education.”

Asked about the program’s expiration last week, Mayor Eric Adams said he “thought it was a good tool” and had been unaware it was expiring; City Hall did not return a request for further comment. Spokespersons for the City Council would not say if lawmakers intend to reauthorize the program, instead saying the legislative body is “proceeding thoughtfully and gathering critical input to pursue effective solutions that make our streets safer.”

This story was updated with comments from DOT and the City Council.