New York’s streets have gotten much safer since the city adopted Vision Zero a decade ago, but the gains have disproportionately benefitted those who live in whiter, wealthier communities.

On entering the mayoralty in 2014, Bill de Blasio joined numerous cities across the globe in adopting Vision Zero as a policy goal, with the ultimate aim of having zero traffic deaths. And Vision Zero appears to have made some difference: traffic fatalities were 16% lower between 2014 and 2023 than in the preceding decade, and pedestrian deaths were 29% lower, according to a new report from advocacy group Transportation Alternatives.

But the safety gains have not been felt equally across the city’s neighborhoods, the group says. When comparing the first five years of Vision Zero to the second half, TransAlt found that majority-white community boards saw a 4% drop in traffic deaths — but majority-Black communities saw a 13% increase in fatalities while the increase in Latino communities reached 30%.

“It’s clear the program has not been fully or effectively implemented in neighborhoods of color and with lower incomes,” reads the report. “This doesn’t mean Vision Zero doesn’t work, but the opposite: it only works as well as it’s implemented and prioritized.”

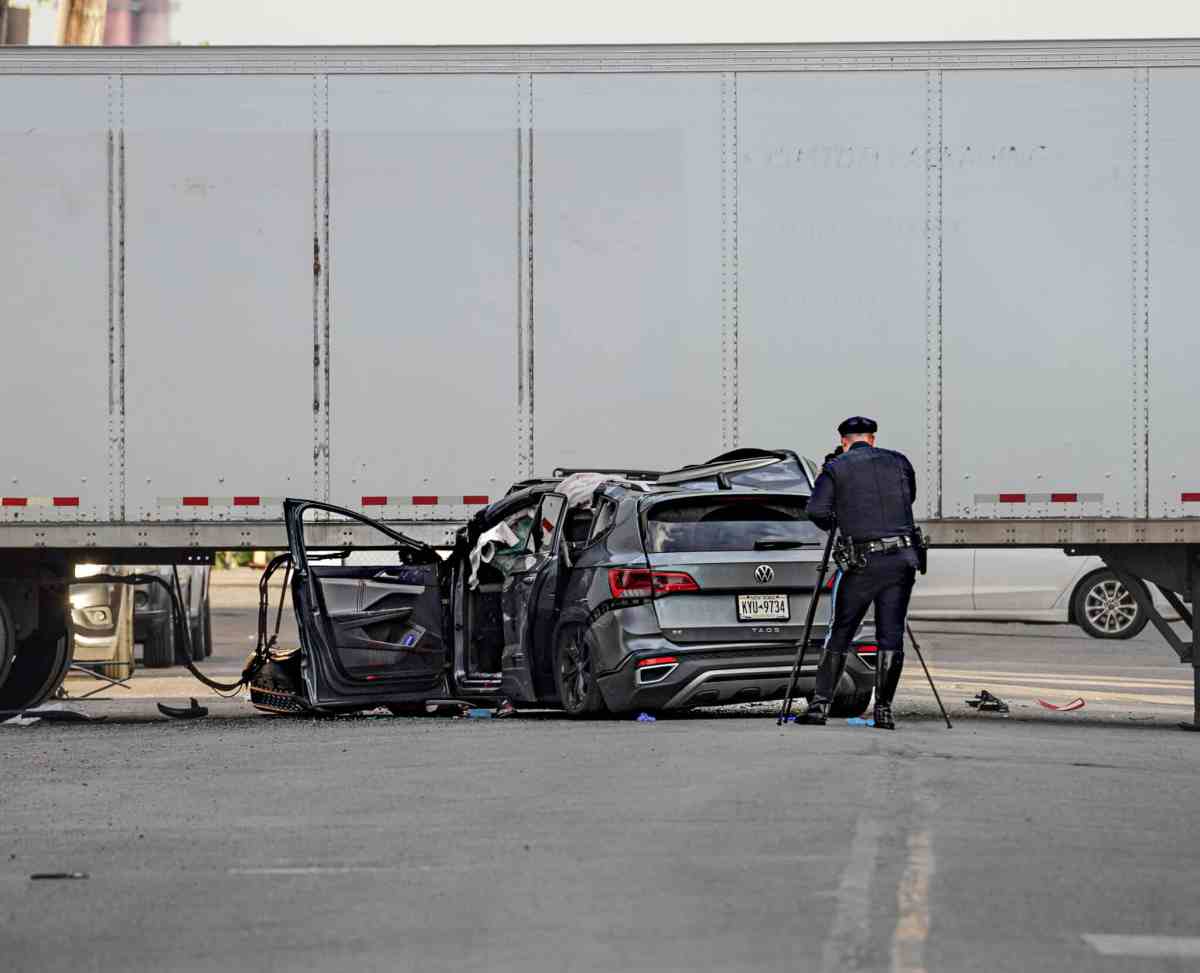

The idea behind Vision Zero is that policy decisions around the city’s streets can help reduce the number of people who die in traffic collisions, which stood at 258 last year, just one below the 259 seen in 2014. Those policy decisions include redesigning streets to make it difficult or impossible to drive recklessly and safer for pedestrians and cyclists, as well as the city’s speed and red light camera program and allowing the city to lower its speed limits.

In New York, bike lanes and other bike infrastructure tend to be more concentrated in whiter, wealthier neighborhoods while neighborhoods of color are left in the dust. The same was long the case for Citi Bike, and while the bikeshare system has since expanded to further reaches of the five boroughs, service reliability tends to be lower in low-income neighborhoods of color, City Comptroller Brad Lander found in an audit last year.

In 2023, 29 cyclists died in collisions on New York City streets — the most of any year in the 21st century.

Meanwhile, pedestrian-minded improvements like Open Streets are also not equally distributed; TransAlt previously found that Black, Latino, and low-income neighborhoods tended to have Open Streets more likely rated as “poor” in quality.

“While we should celebrate an overall decrease in traffic and pedestrian fatalities over the last decade, it is deeply concerning that communities of color are experiencing fatalities at higher rates,” said Queens Council Member Selvena Brooks-Powers, chair of the Council’s Transportation Committee.

In response to the report, a spokesperson for the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) noted the agency’s 2019 Streets Plan includes a formula for investing more resources in neighborhoods with comparatively lower incomes and higher proportions of non-white residents. They said that under the formula, investments have been more concentrated in these “Tier 1” areas and pedestrian deaths have decreased most in areas with high poverty and more non-white residents.

“Since the beginning of Vision Zero back in 2014, NYC DOT has worked to ensure all New Yorkers benefit from safety projects – with Safety Improvement Projects slightly more concentrated in neighborhoods of high or very high poverty than in lower-poverty areas,” said DOT spokesperson Anna Correa. “Our commitment to equity influences where we prioritize our work, weighing neighborhood race and income, density, and history of past projects.”

Read more: Bronx Subway Shooting: 1 Dead, 5 Injured in Violent Incident