Sunday marked the 120th anniversary of the opening day of underground subway service, which commenced on Oct. 27, 1904, with service from City Hall to Harlem.

Looking back, New York City is a vastly different place today than it was 120 years ago, and the subway was an integral part of its development.

“This city was built on this subway system,” said Demetrius Crichlow, the president of MTA New York City Transit, in an interview. “It wouldn’t be the city that it is without the incredible subway system that supports it.”

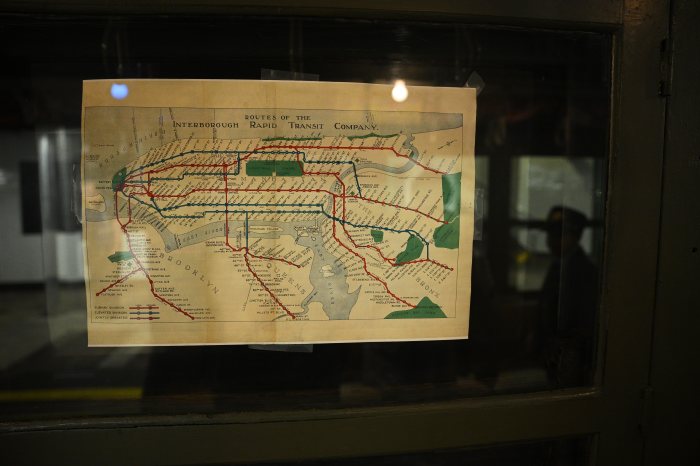

The subway wasn’t New York’s first railroad or even its first mass transit: by 1904, the city was already served by a large network of elevated railroads, or “els.” But the els were noisy, and were paralyzed along with the rest of the city in an 1888 blizzard that convinced much of the New York political class to support building an underground subway — short for “subterranean railway.”

Today we take it for granted, but building the subway was hard work: 7,700 people labored in dangerous conditions constructing the first subway line, with 16 giving their lives. On opening day, though, 150,000 people paid a nickel to ride the subway on its first day of operation, going through 28 stations from City Hall on the modern Lexington Line, running across 42nd Street, and then heading to Harlem on the modern Broadway line.

The city quickly inked new contracts with private operators to build various new lines in Manhattan and the outer boroughs. Especially in Queens and parts of outer Brooklyn and the Bronx, these lines were often built through farmland that would quickly be developed for residential living. Mass transit allowed people to live further and further outside the central city and still quickly get to work in Manhattan.

“It really was the catalyst to transform entire sections of New York, thereby expanding the footprint of where people could live in New York,” said Concetta Bencivenga, director of the New York Transit Museum. “There’s lots of competing theories as to why the five boroughs consolidated in 1898, but six years later the subway opened, and it really became possible to envision becoming what we know now as New York City.”

Like any other 120-year-old, the subway has experienced a lot in its lifetime. The nickel fare now costs $2.90, and the original 28 stations along 9 miles of track have grown to 472 stops across 665 miles of railroad. Those first 150,000 riders gave way to a peak of over 6 million before the pandemic, and ridership is still usually over 4 million on an average weekday now.

While the city has always owned its subway, its operation has changed hands several times, from a slew of private companies to the city to finally the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which was formed in 1968 to pool revenue from transit fares and auto tolls — and neatly disempower Robert Moses, the New York “master builder” who favored highways and auto infrastructure at the expense of mass transit.

Today, the MTA runs the subway, buses, Metro-North, Long Island Rail Road, Access-a-Ride, and various bridges and tunnels.

Meanwhile, the subway has gone through periods of great expansion and significant contraction: hundreds of miles of new lines have been built since Day 1, but on the flipside, many of the old elevated lines were torn down without being effectively replaced by a subway, most infamously along Second and Third avenues in Manhattan.

The subway has faced significant financial pressures that have led to deterioration in service and the physical environment, especially during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s and the “Summer of Hell” in the 2010s.

Today, the MTA says it needs $68 billion to properly invest in maintaining the system in a “state of good repair ” and replacing many dated infrastructure components, such as Great Depression-era train signals and railcars over 50 years old. It is yet unclear if the agency will actually get anywhere close to that sum.

“Looking at the history, you can only honor where we are today,” said Crichlow. “But it also talks about how we need to continue to fund the system, due to the capital work necessary to keep the system going. It’s 120 years, I don’t know many people who maintain anything that’s 100 years old. So it does require a certain level of care, but it also speaks to how we’re able to maintain it, how good a job we do of maintaining it to provide service daily the way that we do.”

Through it all, though, the subway has been the circulatory system of New York City, crucial not just to the economic might of New York but also to its cultural dominance in America and the world.

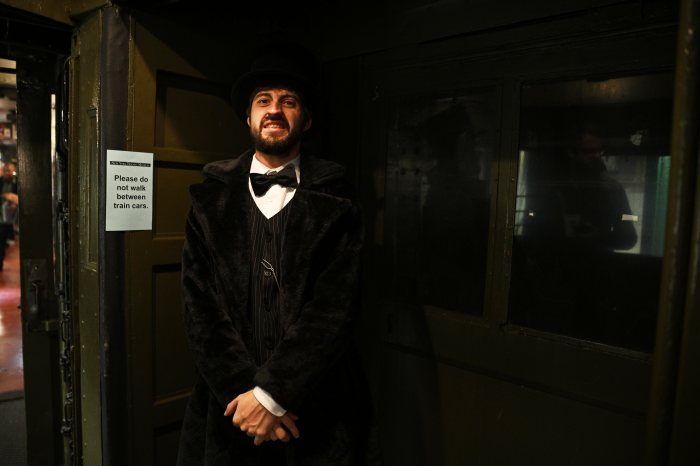

To celebrate the occasion, on Sunday the Transit Museum hosted two of its periodic “nostalgia rides” on rolling stock from its collection of old-timey trains.

Approximately 500 lucky railfans packed onto the two separate rides from the old South Ferry terminal to Harlem on the Broadway line and back to the old City Hall station on the Lexington line using the Standard Lo-V (short for Low Voltage), which dates to 1917 and was notable for requiring much less electricity to run than previous models. Two more sold-out rides are scheduled for Nov. 16.

The Lo-Vs were in service for decades. One rider, Dennis McDonald of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, recalled riding them to high school as late as 1964, when a subway fare cost 15 cents. Others didn’t quite recall the Lo-Vs but nonetheless found the train trip to be a journey down memory lane.

“Growing up in Queens, taking the subway every day to high school, I always had an affinity for the subway,” said Long Island resident Tom Quinn. “I was always fascinated by it. It just takes me back to my youth riding these old trains.”

Younger railfans compared them to the newer rolling stock they’ve become accustomed to.

“It’s a pretty cool train,” said Manhattan resident Michael Rochester. “It’s nice to compare them to the ones we have today, like the R211, R142, and it’s nice to see how the MTA originally came from.”

Riders weren’t the only ones marveling at the history of it all. So was Janet Sloan, the 10-year MTA veteran driving the Lo-V on Sunday.

“It is exciting. Something different, out of the norm, operating a piece of history,” said Sloan. “It also brings a sense of pride in that, because not many people are qualified to do this.”

It’s hard to know what the next 120 years will bring for New York City and for the world, but most people seem to think the subway is here to stay, no matter what the rest of the world looks like in 2144.

“You can bet against New York, but it’d be a fool’s errand. We figure out a way to kind of adapt and change and evolve, and that really is the cadence of this place,” said Bencivenga. “So my money would be on the subway.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/