The Port Authority on Thursday unveiled an ambitious $10 billion proposal to tear down its decrepit, maligned 73-year-old bus terminal and replace it a new one geared toward the commuter needs of the 21st century.

The new terminal would replace the cramped, dingy existing facility built in 1950 with an open, spacious, and airy new 2.1 million square foot concourse designed by British architect Norman Foster. Perhaps more crucially, the proposal would also repurpose existing Port Authority land on the west side into a brand new staging area and ramp for buses to enter and exit directly into the Lincoln Tunnel — which the agency says would eliminate idling buses that have long clogged Hell’s Kitchen streets.

At an announcement with local elected officials at the terminal Thursday, Port Authority honchos were not shy in acknowledging the less-than-stellar reputation the existing terminal has among New Yorkers and tourists who pass through it, but said they intend for the new terminal to be the pride of the west side.

“When the Port Authority Bus Terminal opened in 1950, it was celebrated as a miracle of transportation. But time, as we all know, has not been kind to the Port Authority,” said Rick Cotton, the Port Authority’s executive director. “The bus terminal has become a poster child for failed legacy infrastructure that desperately needs to be replaced. Today, we say loudly, a new day is coming.”

The Port Authority released a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the massive bus terminal project on Thursday, and hopes to gain approval of a final EIS sometime this year. Public comment on the draft EIS will be open for the next 45 days, and four hearings will be held from Feb. 20-22.

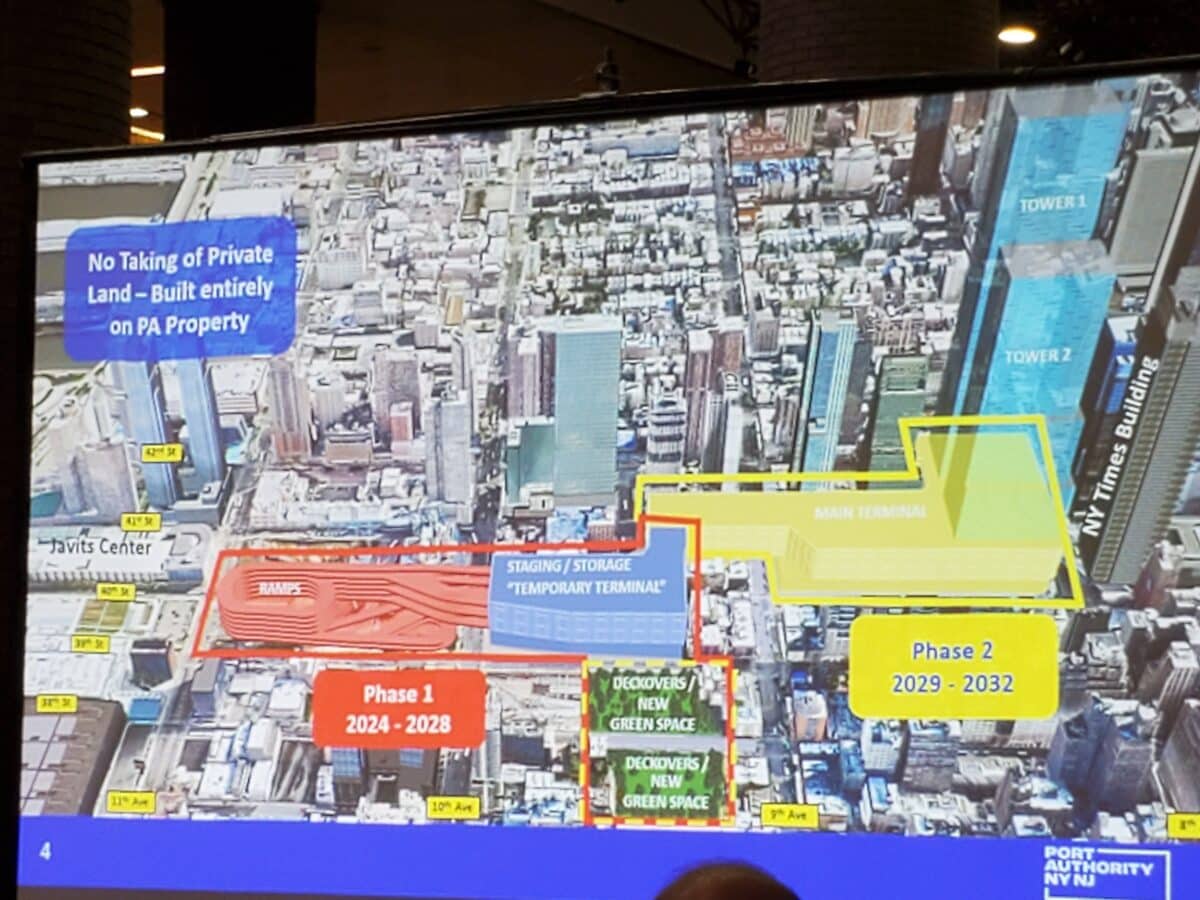

The plan would drastically expand the size of the terminal — already the busiest bus transport facility in the world, with nearly 100,000 passengers on a typical weekday — but the Port Authority owns all of the land that it intends to build on. Eminent domain would not be necessary, nor would any buildings need to be demolished, Cotton said — something which helped bring local elected officials and community members on board for the project.

How it will work

The first phase of the project would involve building the new ramps and staging facility on blocks spanning 39th to 40th streets and most of 9th to 11th avenues. After completion, the existing terminal would be torn down and reconstructed, with a spacious new atrium taking the place of a delisted section of West 41st Street currently underneath the existing facility.

After the facility is torn down but before the new one is completed, the new staging area would be used as the interim bus terminal.

“There will be a lot of construction in this neighborhood, and it will impose serious inconveniences on the neighborhood,” said Cotton. “But we are trying to do what we can to make up for that, which is listen, be responsive, and we are moving forward.”

New Yorkers would be forgiven for being skeptical of the Port Authority’s grand pronouncements for the ugly stepchild of its portfolio. The EIS itself notes the Port Authority has conducted no fewer than 5 studies in the past 11 years on the very question of rebuilding the bus terminal, with none of that effort apparent in the present facility.

This time is different, though, agency bigwigs say.

Almost exactly 10 years ago, then-Vice President Joe Biden famously said that LaGuardia Airport looked like a “third-world country.” Ten years and $8 billion later, it’s an entirely different place, with two brand-new, state-of-the-art terminals welcoming passengers to Big Apple. The agency is also investing billions of dollars into modernizing John F. Kennedy and Newark airports.

“Many of these projects have been talked about for a long time, we’re committed to getting them done,” said Cotton. “They’re getting done, they’re getting done on time, they’re getting done on budget, and we’re confident we can do that for the bus terminal.”

The Port Authority is in a “new age,” Cotton added. “Frankenstein, meet Cinderella.”

Timeline and finances

Cotton said that if the final EIS is approved this year, shovels could go in the ground for the ramps and staging facility in 2024 with construction continuing through 2028. The second phase would begin immediately afterwards and run till completion in 2032.

That’s a big “if,” though, as the project is lacking perhaps the most crucial thing: money. Cotton said the majority of the financing would come from the Port Authority, but a huge portion of the $10 billion price tag is predicated on uncertainties. Funding depends on hashing out a loan agreement with the federal Department of Transportation which Port Authority honchos say they are working on.

About $2.5 billion also would come from “payments in lieu of taxes” (PILOTs) leveraged from the development of new office towers by the bus terminal. It’s a major gamble: such a strategy did work in getting funding for Amtrak’s Moynihan Train Hall at Penn Station. But that was before the COVID-19 pandemic permanently changed how white-collar professionals work, with many rarely or even never coming to an office in the central business district anymore.

Despite that, Gov. Kathy Hochul’s plan to redesign Penn Station originally hinged on PILOTs from Midtown office developments built by Vornado Realty Trust, the wealthy and politically connected real estate firm. Last year, though, Vornado paused development in the Penn District, citing a tightening lending market that made office development less tenable, throwing the whole Penn Station project into disarray. Months later, Hochul said the state was “decoupling” the Penn plan from Vornado and would still happen.

Cotton said that the real estate market of the 2030s cannot be predicted but the Port Authority is confident that New York City’s post-COVID economy will continue to heat up. He cited as evidence the recent $963 million acquisition of 715-717 Fifth Avenue by Kering, the parent company of Gucci, in a deal he characterized as well above what market analysts predicted the property could fetch.

“We have confidence in New York City, we believe in New York City,” Cotton said.

And local elected officials, like west side state Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal, seem to have confidence in the Port Authority’s vision.

“It’s been called Hell on Earth, but that gives Hell a bad name,” Hoylman-Sigal said of the current terminal. “But we’re gonna change that.”