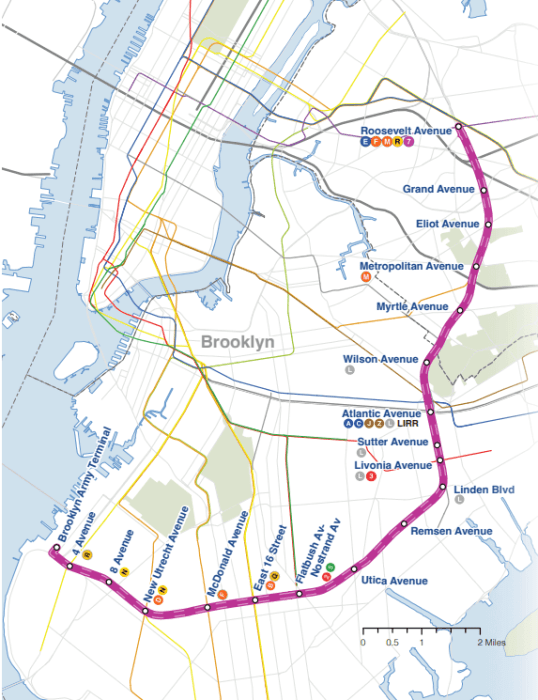

The success or failure of Gov. Kathy Hochul’s marquee transit proposal, the Interborough Express (IBX) connecting Brooklyn and Queens by light rail, is centered on a short, skinny tunnel underneath a Queens cemetery that the MTA says requires the line to be routed away from existing railroad tracks and onto the street.

Based on a long-time dream of transit planners and aficionados, the IBX would utilize existing railroad tracks called the Bay Ridge Branch, which were built for the Long Island Rail Road but have long since been used only by freight, and only about one round trip per day at that. The 14-mile spur runs from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn to Jackson Heights, Queens; Hochul first proposed reactivating the line for passenger service back in 2022.

The project is set to bring rail service to several transit-starved neighborhoods and connect to 17 other train lines, while providing a crucial new link for Brooklyn and Queens residents to move between boroughs without having to take a train through Manhattan first. Hochul has described her vision for the IBX as a “transformative” investment in expanding the city’s transit.

After undergoing a “feasibility study,” the MTA opted not to endorse building a subway along the right-of-way. Instead, the MTA endorsed building light rail, which it has never constructed before in New York City despite being in many cities around the world; the agency said this would be $3 billion cheaper (the overall plan is projected to cost $5.5 billion) without sacrificing speed or capacity.

The basis for that claim lies buried among the dead beneath All Faiths Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens, just across the way from the M train’s Metropolitan Avenue terminus. The cemetery opened for business in 1852, and today its 225 acres are the final resting place for 540,000 people, including the grandparents, parents, and older brother of former President Donald Trump.

Also underneath All Faiths is a short tunnel, about 520 feet in length and 30 feet in width, that freight trains under the CSX banner travel under en route to and from Bay Ridge. The MTA says this tunnel is too narrow to add in passenger tracks alongside the freight ones, and expanding it would be prohibitively expensive and require disturbing final resting places above it.

That, in effect, kills the possibility of using subways on the corridor, the MTA claims. Instead, light rail can be routed out of the railroad right-of-way and onto busy Metropolitan Avenue, turning left on 69th Street before returning to the Bay Ridge Branch tracks after two-thirds of a mile.

Street-running could prove disastrous

But diverting onto the roadway poses myriad challenges of its own. A group called the Effective Transit Alliance contends street-running is the “biggest threat” facing the IBX project as a whole. According to the ETA’s “Interborough Express Done Right” report, the train would have to obey the city’s 25-mile-per-hour speed limit, stop at traffic lights, and make tight turns — and that’s before worrying about the trains getting stuck in traffic or blocked behind scofflaws.

“Any time trains are forced to run on a busy street, travel time increases, and worse, reliability on the entire line can plummet — even for passengers traveling entirely on grade-separated sections,” the report reads.

On-street trolleys used to dominate American cities, but precipitously declined when the advent of the automobile meant trolleys were constantly stuck in traffic and became less reliable. In New York and other cities, trolley tracks were ripped up and streetcars were replaced by buses.

Some cities still have on-street trolleys: Boston’s Green Line runs on a mix of dedicated tracks, physically separated streetcar tracks, and in some cases, tracks running in the same right-of-way as traffic. The Green Line’s E branch largely shares its right-of-way with cars in southern Boston, and is the slowest and least reliable segment of the line, averaging just over 7 miles per hour.

Street running also brings the possibility of trains colliding with cars, which could cause delays throughout the entire line. In Dublin, the Luas tram collided with vehicles, cyclists, or pedestrians 58 times from the beginning of 2021 to mid-2023, according to Transport Infrastructure Ireland.

The ETA sees the same possibilities in the present plan for the IBX, and contends that instead expanding the All Faiths tunnel would “improve speed” and “dramatically increase reliability.”

The MTA has not indicated if the street-running portion would be in a separate right-of-way or mixed traffic; the finer points will be determined in the upcoming design phase. An agency spokesperson said that if done right, they do not see speed and reliability issues arising from street-running. The spokesperson cited light rail systems in Melbourne, Australia, and across the river in Jersey City, as examples where light rail efficiently runs in mixed traffic.

In spots where it runs in mixed traffic, Jersey City’s Hudson-Bergen Light Rail can run at about 25 miles per hour. On sections with dedicated rights-of-way on rail, it can run 60 miles per hour, according to the New York Times.

Cut and cover?

What’s more, the street-running plan has the potential of engendering significant neighborhood opposition, and even lawsuits putting the state on a costly defensive. City Council Member Robert Holden, who represents the area at City Hall, says that he conceptually supports the IBX and the notion of better transit in his community, but called the on-street proposal a “deal-breaker,” and instead endorsed expanding the tunnel.

“If you can’t use the track area, the deal is off,” Holden said in an interview with amNewYork Metro. “It would be a tremendous disruption, and I think you’d also have homeowners fighting. They don’t want their land taken, they don’t want their homes taken.”

Some also believe the MTA is bluffing in its sky-high cost estimates for expanding the All Faiths tunnel.

Alon Levy — a researcher at New York University’s Marron Institute of Urban Management who contributed to the ETA report and whose work focuses on the costs of building transit — believes the MTA can dig the tunnel using the “cut-and-cover” method, which was common when the subway was first built but has fallen out of favor due to the immense disturbance it causes to local communities.

That problem doesn’t necessarily present itself at All Faiths, since everyone there is dead. Cut-and-cover is much cheaper and technically simpler than underground boring, which has become the predominant method of choice for tunnel construction; Levy believes the breadth of cost could easily start with millions instead of billions.

“Because everyone next to where the tunnel would go is dead, they can use cheaper shallow cut-and-cover to add two passenger tracks next to the CSX tunnel,” said Levy. “Done right, it’s in the tens of millions. Even at the per-cubic meter cost of 96th Street on Second Avenue Subway, it’s around $50 million.”

Tens of millions may sound like a lot for a short tunnel, but it’s a lot less than what the MTA says it would cost to route the IBX under All Faiths.

In its planning study, the MTA projected conventional rail would cost $8.5 billion, a $3 billion premium over light rail. An agency spokesperson said that to avoid disturbing graves would require boring a 1.5-mile-long tunnel deep underground, instead of the short shallow dig to expand the current tunnel.

Levy’s estimate is speculation, rather than a former appraisal, an MTA spokesperson said, noting further that they are not an engineer. The spokesperson noted that the agency hasn’t yet determined the feasibility of a shallow tunnel for light rail.

Mausoleum in the way

The MTA didn’t provide a cost estimate specifically for expanding the tunnel under All Faiths, but noted other premiums for subway development include differences in stations, signaling, power systems, storage, and maintenance, as well as the presence of the Fresh Pond rail yard nearby.

However, the existing tunnel does not even go under the grave-dense sections of All Faiths. The tunnel mainly runs under the cemetery’s driveway, and the only resting places that partially run in the way are within the Eternal Light Community Mausoleum, which has space for 552 crypts but is only partially full.

Brian Chavanne, the superintendent at All Faiths, told amNewYork Metro that moving the mausoleum was technically feasible, though it would be a difficult undertaking.

“It’s on pylons, and they go below ground, they go one-deep below ground, encased in cement,” Chavanne noted. “So it’s not just a level to the ground, it’s one down deep, and it’s all cement.”

Moving the mausoleum would also pose complex bureaucratic challenges, with the MTA possibly having to compensate the families of those eternally resting there. The All Faiths board, courts, and the state’s Division of Cemeteries would also need to be involved, Chavanne said.

It wouldn’t be the first time graves were moved for public works projects in the area. A large number of final resting places were disturbed in the 1930s to construct the Jackie Robinson Parkway, a highway link between Brooklyn and Queens that runs through the cemetery belt, an area on the boroughs’ borders densely packed with graveyards. Before being renamed for the barrier-breaking slugger in 1997, the road was known as the Interboro Parkway.

Either way, Chavanne couldn’t say for sure whether the mausoleum would need to be moved at all, and would have to consult an engineer on that question.

That’s because, he said, the MTA has never contacted All Faiths about possibly expanding the tunnel or the transit project generally, and Chavanne said he hadn’t even heard of the IBX until an amNewYork Metro reporter contacted him.

An MTA spokesperson said that property owners along the right-of-way would be consulted in the IBX’s upcoming design phase.

Chavanne also agreed with Holden that, for the Middle Village community’s sake, he preferred running the IBX through the tunnel as opposed to the street.

“That would be total chaos,” Chavanne said of the street-running proposal. “Going through the already underground tunnel, that’s already there, if it doesn’t cause catastrophic displacement inside the cemetery, would probably be better than putting the tracks on the street.”

Avoiding a boondoggle

In a statement, an MTA spokesperson said that nothing has been set in stone yet, and more questions will be answered about the project in the upcoming design phase.

“Gov. Hochul, in her State of the State address last week, directed the MTA to begin preliminary design and engineering alongside the environmental review of the Interborough Express, where all benefits and impacts will be thoroughly studied,” said MTA spokesperson Eugene Resnick. “The Design of this transformational project is still in the very early stages. We will be working with all relevant stakeholders across the project area to ensure a robust engagement process.”

Hochul’s office deferred to the MTA for comment.

The MTA wants to prevent the IBX from becoming an expensive boondoggle, something the agency is all too familiar with.

The first phase of the Second Avenue Subway, which extended the Q to 96th Street, stewed in the idea muck for nearly 90 years and, by the time it was completed in 2017, about $4.5 billion had been spent. Phase 2, which will bring the Q to 125th and Lexington, is currently projected to cost about $7.7 billion, including the cost of servicing debt.

Meanwhile, the mammoth East Side Access project was finally completed early last year, bringing Long Island Rail Road service to Grand Central Terminal. That project, also stewing for decades, formally began planning in the 90s with transit honchos projecting completion within a decade. Ultimately, though, the project was not completed for about 25 years and ran nearly triple its original budget, with a final balance at about $11.6 billion.

MTA bigwigs contend they have learned hard lessons from the boondoggles of the past and have internalized better contracting practices. In 2022, MTA chief Janno Lieber said the agency completed the Third Track project on the Long Island Rail Road’s Main Line “on time and $100 million under budget.”

The IBX is based on a proposal by the Regional Plan Association called the Triboro, which would have extended the line all the way to Co-op City in the Bronx and created the only rail link between the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn. But the Boogie-Down was left out of the final proposal because it would conflict with the MTA’s Penn Access project, which will eventually bring Metro-North trains to Penn Station via the Hell Gate Bridge; that bridge, the MTA contends, isn’t wide enough to fit Amtrak, Metro-North, freight, and the IBX.

Correction: this article originally stated the All Faiths tunnel is 60 feet wide. It is actually 30 feet wide.

Read more: MTA to enhance bike and pedestrian access