More people are driving cars in New York City than ever before, based on toll data from the MTA and Port Authority — a remarkable feat as the city prepares to implement congestion pricing in the hopes of dissuading motorists from getting behind the wheel in favor of mass transit.

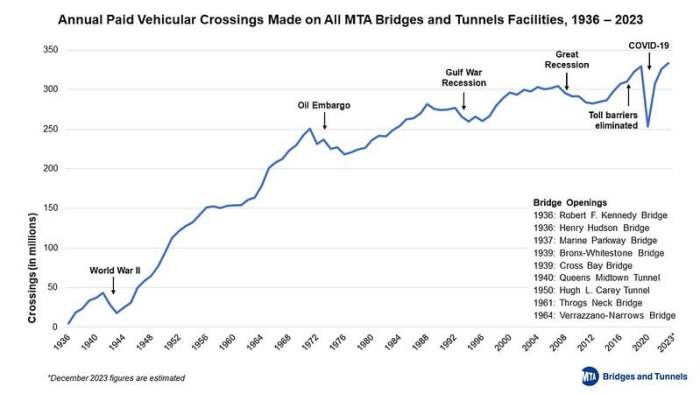

Over 335 million vehicles were recorded crossing the MTA’s nine bridges and tunnels in 2023, which include the Whitestone, Throgs Neck, Cross-Bay, and Verrazzano-Narrows Bridges and the Brooklyn-Battery and Queens-Midtown Tunnels, among others. That’s a 1.3% increase over the previous record in 2019, when 330.7 million crossings were made, and the most ever seen in 87 years of data collection.

In 1937 — the first year that the MTA Bridges & Tunnels’ predecessor, the Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority, was in operation — the bridges saw only 18.5 million crossings. Back then, the TBTA had only three bridges in its portfolio: the Triborough Bridge, the Henry Hudson Bridge, and the Marine Parkway Bridge.

The Port Authority, meanwhile, has this year seen the highest number of vehicle crossings on its six spans — including the George Washington Bridge, Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, and the Bayonne and Goethals Bridges and Outerbridge Crossing connecting Staten Island and New Jersey — since at least 2011. Through October, the latest month that data is available, the Port Authority had recorded just over 102 million crossings.

In its 2024 budget proposal, the Port Authority projected its bridges and tunnels would see 122 million crossings next year.

New York City’s Department of Transportation could not immediately provide numbers for its bridges throughout the city, which include major spans like the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges and hundreds of short crossings all over the five boroughs. Unlike the MTA and Port Authority, the DOT does not collect tolls.

However, DOT did record that the number of vehicles registered in the city grew more than 10% between 2010 and 2021, according to the agency’s Streets Plan update earlier this year. The numbers for 2022 will be published in early 2024.

Motor vehicle traffic has generally been on an upward trajectory since the start of data collection, though volume has dipped at various points coinciding with World War II, the 1970s oil embargo, and the Great Recession, according to the MTA. The last major dip was at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when millions of New Yorkers were told to stay home and stop the spread of the coronavirus.

Car traffic in the city has fully rebounded to pre-COVID levels, as has passenger volume at the tri-state area’s airports. That’s despite the fact that mass transit ridership continues to lag well behind pre-COVID numbers, as more and more New Yorkers choose to work from home.

Subway ridership has hovered at about 60-80% of pre-COVID numbers, which posed a severe fiscal crisis for the MTA as it prepares to wean off COVID-era federal budget support.

While the fiscal crisis was resolved for the next few years in the most recent state budget, transit ridership continues to lag, even when counting the many people who ride transit without paying the fare.

The record number of bridge and tunnel crossings in recent years is also likely an undercount, as the city has seen an explosion in “ghost cars” driving around with phony or obstructed plates, or even no plates at all.

Since most tolls are now collected via automated cameras, drivers with fake plates can skirt through without paying, while also avoiding camera-issued tickets for speeding, running red lights, and parking in bus lanes.

Impact of congestion pricing

Record traffic comes as the MTA prepares to implement congestion pricing, which will levy a toll for motorists entering Manhattan’s central business district south of 60th Street. The MTA has formally proposed that most motorists pay $15, with higher fees for trucks and discounts overnight, and hopes to implement it by spring of 2024.

The congestion pricing plan, passed by the state Legislature in 2019, aims to reduce Manhattan’s punishing gridlock, which slows down emergency vehicles and city buses, and incentivize those who would otherwise drive to take mass transit.

“By cutting traffic while funding public transit upgrades, congestion pricing could not come in a better year than 2024,” said Danny Pearlstein, spokesperson for the transit advocacy group Riders Alliance. “The irony is that drivers are more eager than ever to pay tolls to beat traffic, while politicians fall all over themselves to oppose congestion pricing.”

The revenue would fund the MTA’s capital plan, including replacing ancient subway signals, making the transit system accessible for people with disabilities and resilient to climate change, and keeping the century-old subway in a state of good repair.

Read more: Emergency Brakes Misused by Vandals, Says MTA Chief