Rideshare drivers are hoping this year’s crisis of “lockouts” from Uber and Lyft will gain the attention of regulators at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

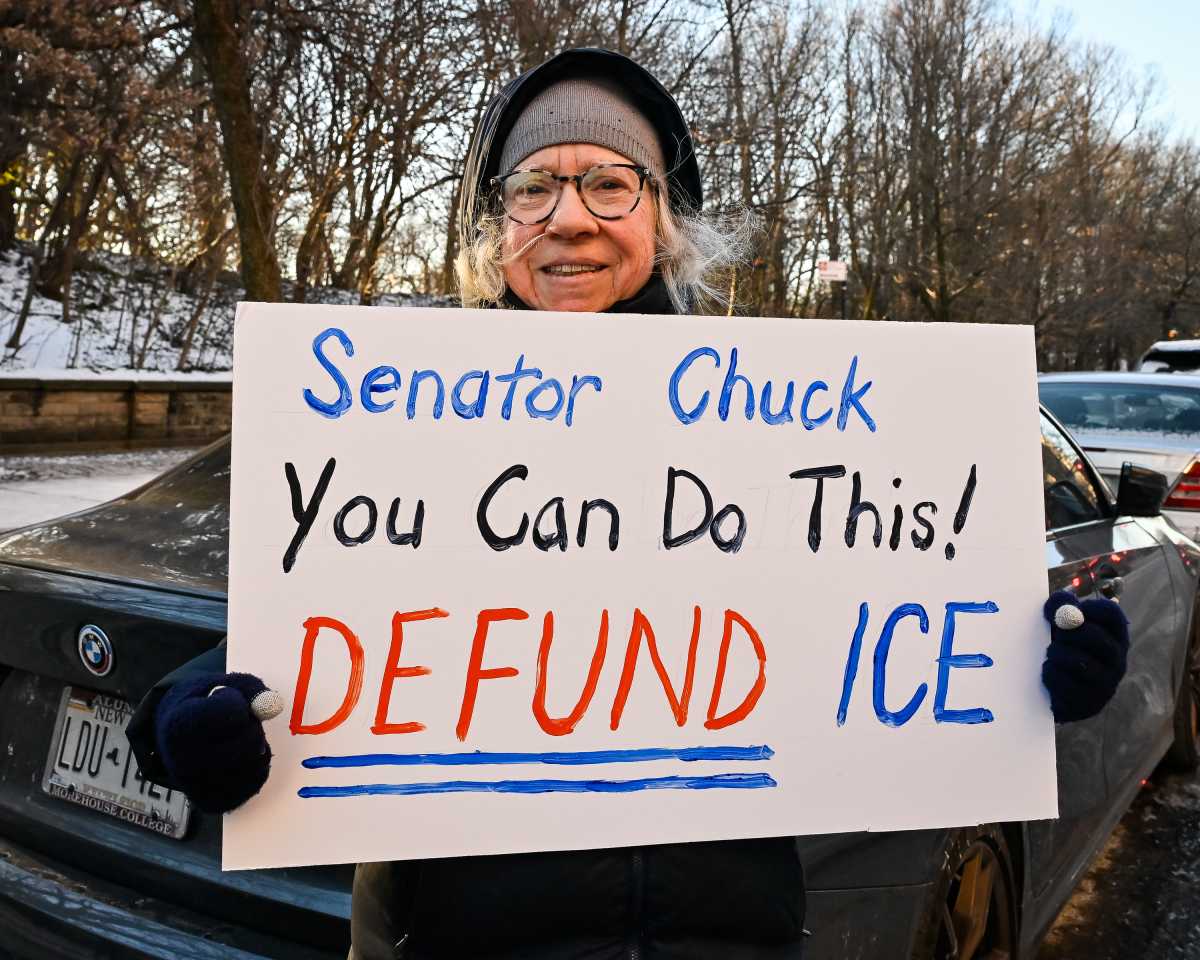

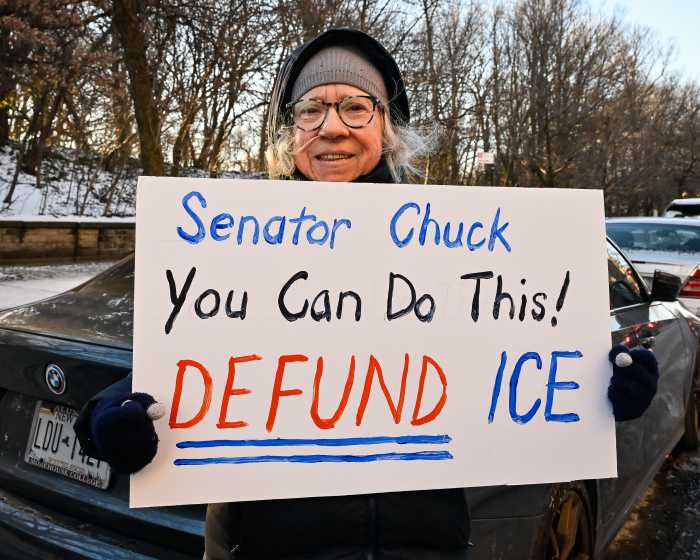

Drivers organized by the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) on Monday presented chilling testimony to Alvaro Bedoya, one of the FTC’s five commissioners, on how the rideshare giants’ recent practice of preventing them from logging onto the apps have impacted their lives — alleging it amounts to collusion.

Since this summer, drivers have frequently found themselves locked out of either the Uber or Lyft app, which NYTWA argues is a means to juice a stat reported to the city critical to determining how much drivers are paid. The consequences, drivers say, have been dire.

“It can last for hours, days, and once I was not able to go online for three weeks,” said Alpha Barry, who has driven professionally for 20 years. “I’ve got family to feed, rent to pay, and other expenses like car insurance and car maintenance. This past month, I had to go into debt and borrow money to pay my rent.”

NYTWA says the situation was not helped by a city-brokered deal this summer, following protests by drivers and threats of tighter regulation by the Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC), that Mayor Eric Adams said would end the lockouts. The deal with Uber and Lyft was supposed to end the lockouts by last month — yet the NYTWA argues the problems remain because the deal effectively required Lyft to increase lockouts while Uber decreased them

“It was phony because it claimed that it was the end to the lockouts, and yet the deal was Uber reducing lockouts is contingent upon Lyft essentially increasing lockouts,” said Bhairavi Desai, NYTWA’s longtime executive director. “So how on Earth is that a deal that ends lockouts? Only thing that’s happened is now, the two companies coordinate their lockouts.”

NYTWA argues that this practice constitutes illegal collusion between the two rideshare giants and should be quashed by the FTC, the federal regulatory agency overseeing the government’s antitrust and consumer protection policy. Desai and numerous rideshare drivers made that case to Bedoya at a Monday afternoon listening session at Fordham Law School.

Bedoya is one of five commissioners on the FTC; he told amNewYork Metro before the session that should he identify practices that warrant further inquiry, he could bring it to the other members of the FTC and potentially refer it to law enforcement to investigate further. Bedoya listened intently to the grievances outlined by drivers, taking particular interest in the mechanics of how they get deactivated on the apps.

“What you have shared with me is something that I will remember,” Bedoya told the drivers following the session. “I’m going to go back and meet with my staff to try to think through everything you shared with us. And like I said, you know, at the start of this meeting, I cannot promise anything. But what I can do is promise you that I’m going to take what you’re telling me very seriously.”

Utilization rate

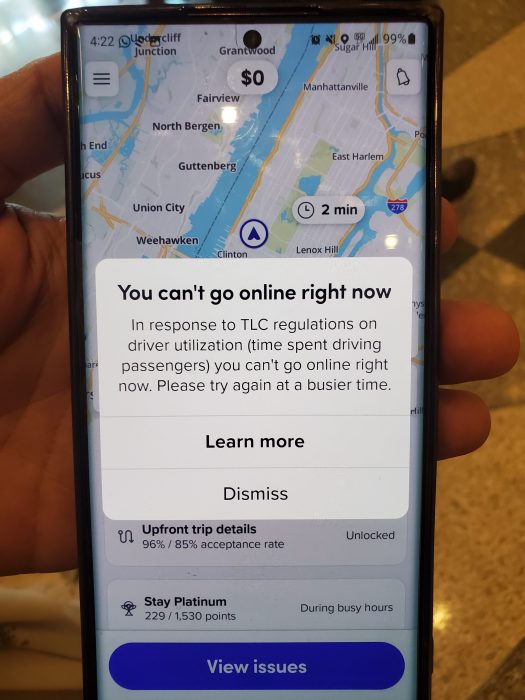

The statistic NYTWA says the apps are juicing is called the “utilization rate” (UR), which measures the proportion of drivers’ time spent actually carrying passengers and making money versus their total shift time.

The metric, unique to New York City, was developed as part of its nation-leading minimum pay standards for rideshare drivers. This ensures that drivers are paid for all the time they’re online while still regularly picking up fares. Per TLC rules, Uber and Lyft are supposed to maintain a UR of over 53%.

According to NYTWA, the problems began last year, when the city lifted its longstanding cap on e-hail vehicles and allowed thousands of new Uber and Lyft cars to enter the market. This created more competition for rides and, by extension, kept drivers’ cars empty for longer periods of time.

By the summer, the apps had each started locking out drivers when too many were out looking for fares. Drivers told Bedoya that they could be locked out if they paused the app even for a few minutes just to get breakfast or go to the bathroom.

“Some days I would spend the whole day driving around, wasting fuel and my time,” said Lyft driver Saif Aizah. “And this puts a lot of stress on me mentally, and a very big burden. Sometimes I feel like I will have a mental breakdown.”

Aizah had previously been deactivated by Uber—essentially a permanent lockout—and so can only drive for Lyft. This already limits his income because of Lyft’s smaller market share. Like Barry, Aizah said that since the lockouts began, he has had to max out his credit cards and borrow money just to pay basic expenses like rent, bills, and car insurance.

The city presented its July deal as a fix to the issue, but drivers are still finding themselves locked out of both of the apps on what they contend is an arbitrary basis. As of July, Uber’s UR stood at 55.1% while Lyft’s was 47.6%.

‘We need a long-term fix’

Reached for comment, a spokesperson for the TLC said the deal with the apps was meant to be a short-term solution while the agency crafted new rules to address lockouts. The rideshare companies’ actions had “defied the intention” of the TLC’s existing rulemaking, said the spokesperson, Jason Kersten, and the agency plans to amend them.

“The harmful lockouts we’ve recently seen happened because billion-dollar companies intentionally exploited loopholes in our minimum pay rules to avoid paying hardworking drivers more,” said Kersten. “Drivers are more than what Uber and Lyft refer to as ‘supply’: they are human beings who deserve the protections our city intended.”

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for Lyft said that the lockouts are simply the company’s response to onerous rules from the TLC regarding minimum pay.

“Lockouts are unfortunately the direct result of the City’s complex driver pay system,” said the Lyft spokesperson, CJ Macklin. “It forces limits on when drivers can earn, ensures riders have to wait longer and keeps Lyft from serving New Yorkers the way they expect. This poor experience is why we don’t deploy lockouts anywhere else except in this unique situation, and it’s why we need a long-term fix.”

Macklin further contended Lyft began undertaking lockouts are solely a response to Uber’s doing the same, accusing the larger company of “using drivers as pawns in its effort to gain an unfair advantage that would leave drivers and riders worse off.”

A representative for Uber declined to comment.

Appealing to the feds is just one tactic in NYTWA’s toolkit to fight lockouts. The union has also considered going on strike and filing antitrust litigation against the rideshare giants and the city, and is pushing the City Council to pass a rule requiring just cause for deactivations.

NYTWA is also pushing the TLC to amend its formula for UR by requiring the metric be measured from the time a driver attempts to log in to the app until they voluntarily log off or are logged off for disciplinary reasons.

“It’s not just stopping the actual lockouts. It’s also preventing the wage fix, preventing the low pay that the lockouts were meant to keep in place, said Desai. “The campaign will be won when we get the TLC to recognize that the utilization rate that they’re looking at now during the lockout months is manipulated data they cannot be relying on.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/