A Texas startup is hoping to zoom into New York’s aerial tourism business by letting customers fly personal, ultralight helicopter-like craft over city airspace — with no pilot’s license and less than an hour of training.

Austin-based LIFT Aircraft has partnered with Charm Aviation, a local heli-tour company, on a proposal to bring personal electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) vehicles to Manhattan’s waterfronts, claiming they provide a less noisy and more environmentally-friendly alternative to tourists than a big helicopter — one that they can pilot all by themselves.

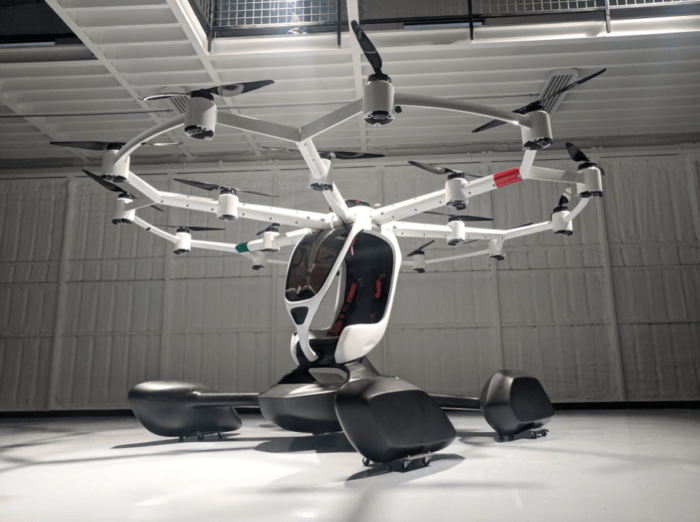

LIFT’s HEXA aircraft looks a bit like a helicopter, but seats only one and is powered by electric motors and 18 independently-controlled propellers above the cabin. The vehicle, capable of touching down on both land and sea, first flew in 2018 in Hungary, and the company has already been approved for its first “vertiport” in Austin, with hopes of further expansion.

Helicopter traffic in city airspace has caused high-flying controversy among many residents, concerned by the extensive noise and air pollution emitted from personal choppers often ferrying rich people to the Hamptons. In June, Brooklyn City Councilmember Lincoln Restler introduced a bill to ban “non-essential” helicopter flights from using the city-operated heliports in the Financial District and Midtown. The bill has 23 co-sponsors, out of 51 total council members.

LIFT devices have just 1/10 the “acoustic signature” of a traditional helicopter, said CEO Matt Chasen in an interview with amNewYork Metro, and are powered by propellers and electric batteries, making them quieter and more environmentally friendly than your average whirlybird.

“[Helicopters] are just wildly loud, which is why people hate them,” Chasen said. “We think this really will be much friendlier to major cities and can be part of the solution to, how do we get people access to flying.”

Charm has already agreed to pre-order 100 HEXAs, in the hopes they be deployed at multiple vertiports across the city and metropolitan area over the next five years, starting in 2023. While it would be introduced to New York as a tourist experience, Chasen says he hopes that ultimately, there could be a network of vertiports all over the city as people take to the skies for their daily commute, skipping the congestion of the ground below.

“We think it’s a great approach to sort of introduce this new technology and this new mode of transportation into the world,” Chasen said. “We think that’s the way to do it, is to not be so intrusive and let communities get to see these things in a less intrusive manner before people start flying over cities and landing on rooftops.”

The vehicles have a maximum cruising speed of 55 knots, or around 63 miles per hour, and can be flown for a maximum of 15 minutes, the company says. Federal Aviation Administration rules limit flights in the area to “uncongested” airspace, like the city’s waterways, and the companies say the HEXA would be “geo-fenced” into flying only in allowable corridors; for one, they hope the airspace could include a view of the Statue of Liberty like no other.

“I can’t wait to fly HEXA around the Statue of Liberty,” said Charm president Caitlyn Ephraim in a statement. “We think this is the future of the helicopter tour market.”

Chasen says that FAA “Class G” airspace where HEXAs could feasibly operate extends up to 1,300 feet over the city’s waterways — almost the height of the Empire State Building. Beginners would likely only fly about 50 feet in the air, and the geo-fence would prevent customers from exiting the pre-determined area. LIFT crew would remain on the ground and in communication with air traffic control.

The companies cite 1980s-era rules from the FAA governing the operation of “ultralight” aircraft as allowing HEXA’s operation in the city. Vehicles can weigh a maximum of 254 pounds, not including parachutes and floats (which contribute to HEXA’s 432-pound weight), and can travel at a top speed of 55 knots. If the standards are met, then flyers do not need a pilot’s license.

To learn how to fly in less than an hour, participants who fork over the $250 entry fee train in a virtual reality simulator before they’re ready to take to the skies. The eVTOL can be controlled by a joystick or put on autopilot using a touchscreen; if the joystick is released, HEXA automatically goes into autopilot. Should the vehicle be running low on battery, LIFT says it will automatically return to base for a recharge.

“With these types of vehicles, the pilot is directing the aircraft where to go, but the pilot is not directly manipulating the control surfaces,” Chasen said. “There’s a computer in between the pilot and the control surfaces, and the computer is basically stabilizing and controlling the aircraft, but the pilot still of course tells it where to go. And what’s great about that is…you can limit what the pilot can do to limit any adverse outcomes.”

Despite the company’s assurances of safety through rigorous product testing, the technology has not yet been proven in a commercial setting, let alone one where customers fly it themselves around America’s densest city. Other companies in the industry have seen their prototypes involved in crashes; one company, Joby, saw its eVTOL prototype crash in California while flying at 270 miles per hour.

In some cases, the machine’s electric batteries caught aflame, a phenomenon also of major concern in electric cars and bikes. Other failures have come as a result of software glitches, like one where the machine’s computer thought it was on the ground and shut off power mid-flight.

The potential for catastrophic accidents is heightened in New York City, with more people and skyscrapers than any other city in America, all packed in like sardines. Restler, for one, called LIFT’s proposal “bats**t crazy” and a “disaster waiting to happen.”

“The idea that one hour of training could prepare somebody to operate a 400-pound potential death trap in the middle of the most congested area in the country is mind-boggling,” Restler said in an interview. “The FAA needs to step up and step in and stop this from happening yesterday.”

“I do think that a more environmentally sustainable and less noisy way to get around is worth researching and exploring,” the councilmember continued. “But any aircraft requires rigorous training to operate. And this fly-by-night operation should never be an accessible mode of transit in the New York City area.”

LIFT assures the public that its vehicles have ample redundancies built in to prevent accidents: there’s the geo-fencing and autopilot capabilities, for one. Further, the machine comes loaded with a ballistic parachute, and it can keep flying even if several of its 18 electric motors stop running.

“Obviously, accidents do occur with any type of vehicle eventually,” Chasen said. “We’re going to limit flights initially to over uncongested areas and waterways, so that accidents would only likely result in the aircraft itself and not have catastrophic consequences on property or people on the ground they might be flying over.”

LIFT and Charm hope to have their first Big Apple waterfront vertiports opened on a trial basis by next year, but will need FAA approval to do so in city airspace. Reached for comment, agency spokesperson Ian Gregor said “the FAA will evaluate any proposal we receive from the company.”

The city’s Economic Development Corporation declined to comment on whether the quasi-governmental agency would permit HEXA flights from its heliports, citing “open procurement for an operator.”

“While we cannot comment on the substance of the proposal due to the open procurement for an operator for a city-owned heliport, NYCEDC supports innovation across sectors while ensuring New Yorkers’ quality of life and safety remain top of mind,” said EDC spokesperson Regina Graham.