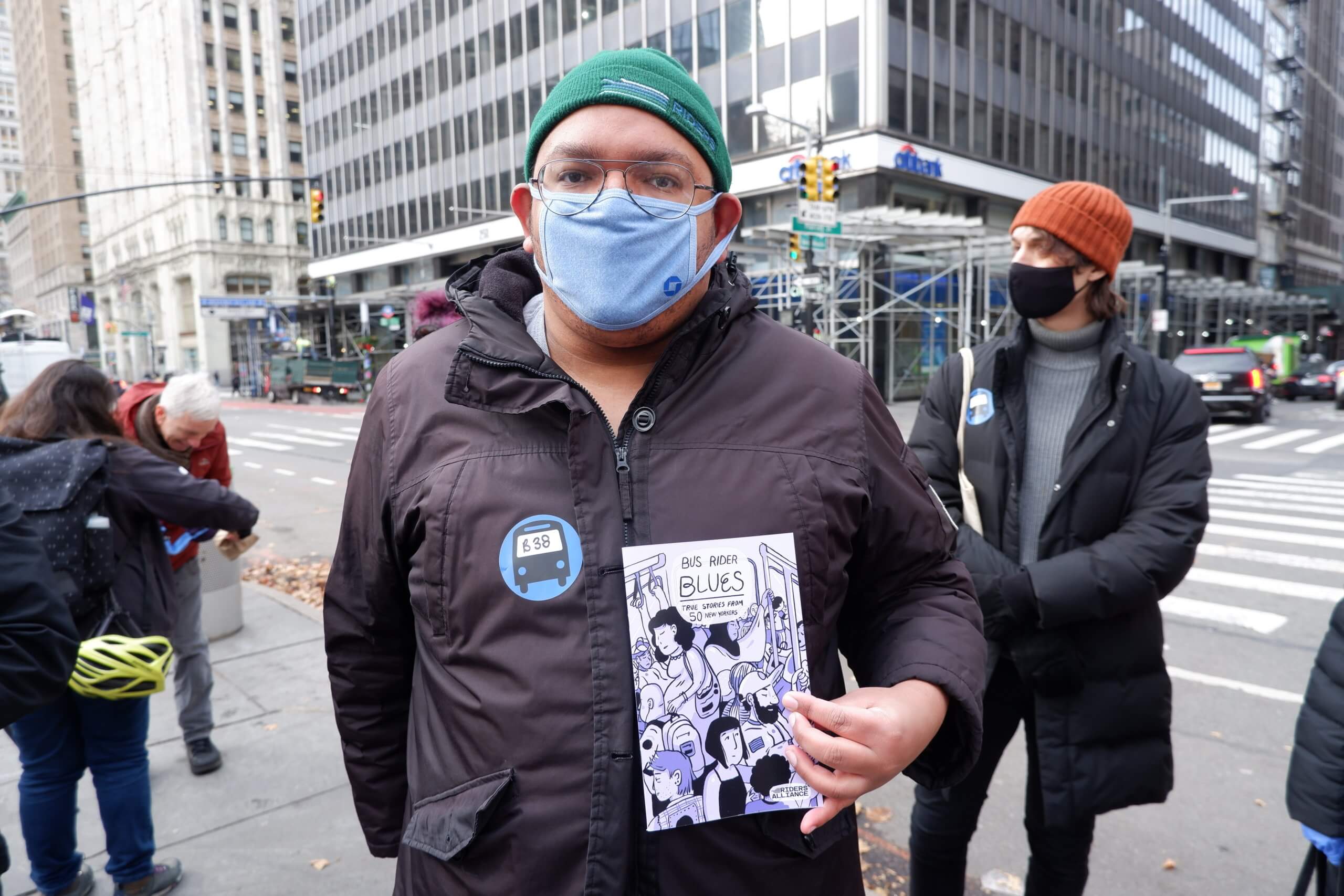

Public transportation activists released “Bus Rider Blues”, a collection of stories detailing riders’ struggles with New York City’s notoriously slow and unreliable bus system, while rallying outside City Hall for better service Tuesday, Dec. 7.

The compilation, released online by the advocacy group Riders Alliance, features 50 true transit tales of straphangers stranded waiting for buses that either never came, or were hopelessly stuck in endless gridlock traffic.

Riders relayed some of their harrowing experiences, such as one City College student from Upper Manhattan who tried to take a crosstown Bx12 to the Bronx, only to be almost left behind by a rerouted bus.

“We then spotted it on the adjacent avenue, nowhere near where the bus stops was,” said Abram Morris at the Tuesday press conference. “And then the bus took 45 minutes to make one single stop.”

A Jamaica, Queens, senior who regularly traverses the borough on half a dozen different lines said she struggles to find a seat on the packed buses, despite relying on a cane to move around.

“The front of the bus is so crowded, I have to push my way back to get through it,” said Jeanne Majors. “I’m afraid I will fall and hurt myself.”

“I want more buses on routes and more reliability so that buses aren’t as crowded,“ the 72-year-old added.

With car traffic returning to pre-pandemic levels, bus speeds slowed down in all Five Boroughs in recent months, according to the latest statistics from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Citywide average speeds in October were 7.9 miles per hour, down from 8.3 mph in October 2020, as car traffic has returned to near pre-pandemic levels.

That’s almost as slow as in 2017, when New York City buses famously came in dead-last for bus speeds of any major American city at 7.4 mph.

Traffic has been so bad near chokepoints like the Holland Tunnel that the MTA had to cut short its crosstown M21 bus two-thirds of all weekdays earlier this year.

One regular rider of the B54 said he has to wait for his bus at least 20 minutes at the western terminus of the line at Jay Street in Downtown Brooklyn to commute to his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, all while out-of-service buses wait — or bunch in transit jargon — as people are forced to wait outside.

“It’s frustrating for me along [with] almost a dozen other riders year-round, either during a major snowstorm during the winter or a severe thunderstorm during the summer,” said Pedro Valdez-Rivera.

The city’s Department of Transportation, which manages the streets, recently made the Jay Street busway permanent after piloting the restrictions on car traffic along the 0.4-mile stretch for more than a year.

However, the red lanes aimed at speeding up rides for tens of thousands of riders have been routinely blocked by drivers illegally going down the corridor or leaving their cars double parked, said Valdez-Rivera, an experience backed up by recent DOT data.

At the Tuesday rally, MTA acting Chairperson and CEO Janno Lieber made a surprise appearance.

“This is not a usual thing, the MTA chair to come to a demonstration by advocates,” said Lieber. “But I gotta tell you, you know who else is dissatisfied with bus service? This guy.”

The transit bigwig said the city needs more bus lanes, busways, and to stop scofflaw drivers from hogging the lanes — all issues that are the city’s responsibility, not the state-controlled MTA.

“That’s what’s gonna make a difference,” said Lieber. “I’ve been riding the bus since I was six years old, my brother and I got to school that way. I ride the B35 now on Church Avenue, and you know — you know — it can be little while, right?”

The MTA has several of its own tools that could accelerate buses, but the proposals have taken a backseat.

The agency relaunched its borough-by-borough redesigns of the city’s ancient bus networks in August, starting with the Bronx this fall, after a 17-month pause due to the COVID-19, but the overhauls for all boroughs won’t be complete until 2026, five years behind the original schedule.

Advocates have also called on MTA to allow back-door boarding on buses using the new tap payment system OMNY. The agency currently plans to start testing it on 10 local routes some time before the MetroCard is phased out in 2023, even though the readers are already on all buses and transit officials could simply switch them on and immediately shave off time spent loading passengers at stops.

Another method is the proposed toll for drivers entering Manhattan below 61st Street known as congestion pricing, which promises to get more commuters out of cars and into public transit, but the scheme is going through an extensive environmental review slated to last until 2023.