The subway will turn 120 years old this month — and the New York Transit Museum is reflecting on what this milestone means to The Big Apple.

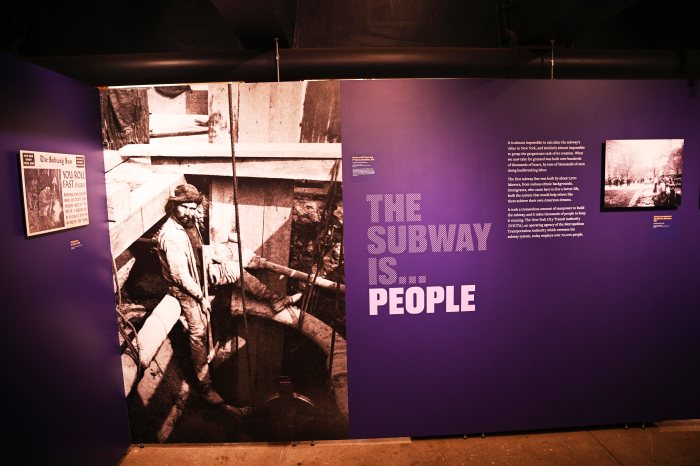

The museum in Downtown Brooklyn has launched a new exhibition, “The Subway Is…,” in honor of the subway’s birthday and intends to run it for at least a year.

Opened last month, the exhibit is meant to be as open-ended as the ellipsis in its title: the subway is so crucial to New York’s history, development, identity, and culture that it means many things to different people.

“At the end of the day, New York is New York because of the subway,” said Chelsea Newburg, press officer at the Transit Museum, during a recent tour of the exhibit. “When the subway opened 120 years ago, it changed the whole city. New York did not look the way that it did before. And you can see a lot of that in the show.”

The first subway line opened on Oct. 27, 1904, running from City Hall to Grand Central along the present-day Lexington Avenue line (4/5/6), heading west on the current 42nd Street Shuttle line, and then moving north along the present Broadway line (1/2/3) all the way up to Harlem at 145th Street. Some 150,000 New Yorkers paid the nickel fare to ride the subway on its first day of operation.

The subway wasn’t New York’s first rapid transit system, of course.

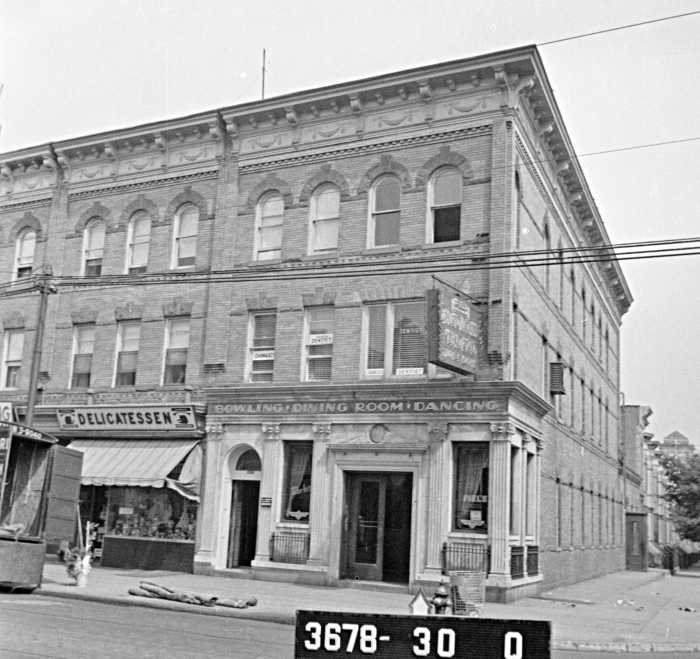

Those were the elevated lines (Els) that crisscrossed the city starting in the 1870s, enabling the Big Apple to spread out with New Yorkers living relatively far from where they worked for the first time. Some of the original elevated system remains in service for the subway: some of the oldest stations in the system are not on the original subway line but, in fact, along the Broadway Line in Bushwick, Brooklyn, that presently serves the J and Z lines.

But the Els had limitations. For one, they are extremely noisy, as New Yorkers who live near elevated lines today can attest.

And when a massive blizzard hit the city in 1888, the elevated lines were paralyzed, helping build support for future railroads being built underground. Unlike the Els, which were built by private companies, the city would build the first subway lines — which were initially leased to private operators like the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT).

By today’s standards, the original subways were built fast and efficiently, but it was extremely dangerous work. Some 7,700 laborers worked on building the subway, with 16 deaths reported from construction on the original line, fewer than recorded while building the Brooklyn Bridge. Many others were grievously injured.

It was also incredibly complex engineering work, with labor done around existing underground utility lines carrying water, sewage, and electricity, many of which had to be re-engineered.

“Imagine a surgeon who has to direct a probe from the neck of a patient all the way to each heel…He must not hurt a single nerve or break the wall of any vein or artery. Nerves, tendons, veins, and arteries must all be avoided, or pushed aside and protected, wherever the probe encounters them. Above all, the tranquility of the patient must not be upset,” said John B. McDonald, chief engineer of the original subway, in 1902, per the exhibit. “There, you have a fair likeness of what had to be done in digging the rapid transit tunnel.”

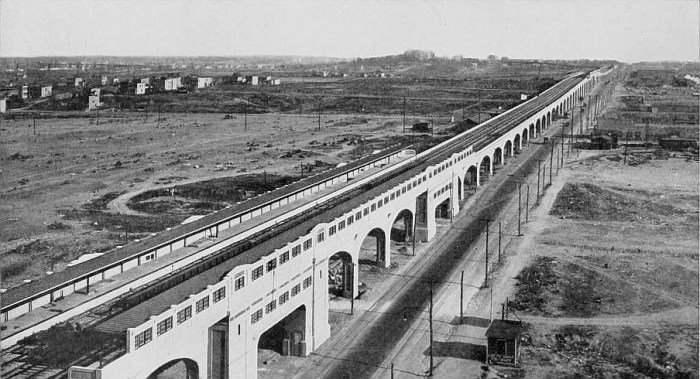

By the time the subway was completed and in service, though, New Yorkers already couldn’t live without it, and contracts were drawn up to greatly expand the system throughout Manhattan and the outer boroughs. Many of the subway lines traveled through sparsely populated regions of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and especially Queens, transforming these areas into residential and commercial hubs.

Even today, with seemingly every square inch of New York City occupied, a new subway line can transform a neighborhood: in just a few years, Hudson Yards has transformed from a run-down area surrounding a train yard to one of the city’s biggest high-rise residential and commercial neighborhoods, anchored by the 7 train extension completed in 2015.

Hundreds of miles of subway had been built by midcentury, such that many of the original elevated trains were torn down in anticipation of a replacement, most infamously the lines along Second and Third Avenues in Manhattan; planners expected them to soon be replaced by the Second Avenue Subway.

The exhibit describes the subway as the city’s “circulatory system,” crucial to how we get around and to how our hometown has developed, and traces how the subway has become an icon of pop culture and informed how we live our lives in New York.

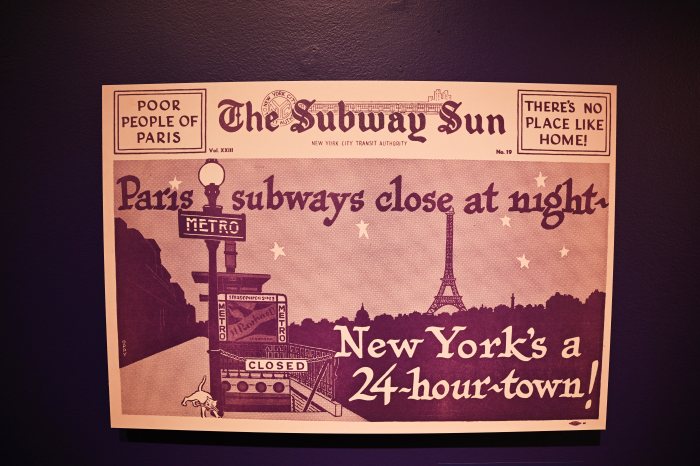

One old advertisement, a PSA from “The Subway Sun,” puts that in stark perspective: unlike Paris, whose Métro closes at night, New York is a 24-hour town, largely because it has one of the world’s only 24 hour metro systems.

“Paris subways close at night, New York is a 24-hour town,” said Newburg. “And that kind of goes to this idea that New York is the city that never sleeps. And the subway is what lets us live like that. It keeps us moving all the time, wherever we need to go.”

For the big birthday on Oct. 27, the Transit Museum will run its periodic Nostalgia Rides along the original route, using the 1917 Lo-V (short of Low Voltage) cars in its collection of old-timey rolling stock. Another ride will take place on Nov. 16.

“The Subway Is…” is open at the New York Transit Museum at 99 Schermerhorn Street in Brooklyn.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/