A group of Upper West Side locals, supported by area pols, are seeking to torpedo a planned crosstown bus lane on 96th Street, arguing the intervention to speed up buses is out of place on “residential” blocks of the tony neighborhood.

The Department of Transportation (DOT) is planning to construct a bus lane on 96th Street, a major crosstown route between the Upper East and Upper West Sides, by the end of this year, aiming to speed up the M96 bus, which has about 15,000 daily riders but putters along at pathetic speeds of about 6.4 miles per hour on average.

At peak hours, speeds can be as low as 4 miles per hour, according to the DOT.

The M106, which travels on 96th on the transverse through Central Park and the Upper West Side, is barely any better, averaging 6.7 miles per hour. Both the M96 and M106 buses clock average speeds below the citywide average of 8.1 miles per hour — which itself makes New York City’s buses the slowest of any major American city.

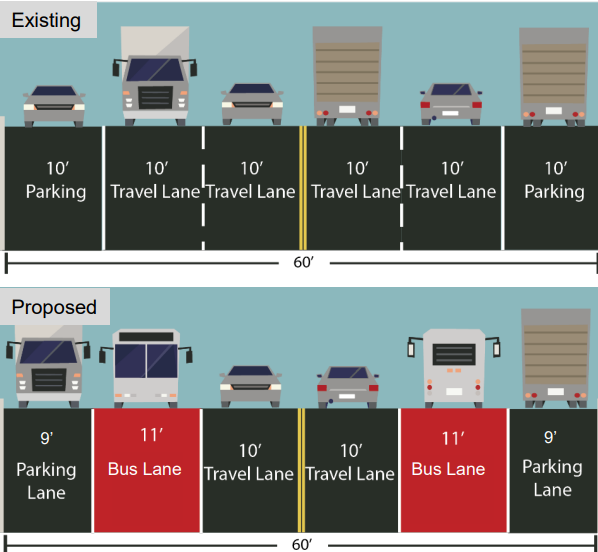

The DOT’s plans call for an offset bus lane, where the curb is still available for parking but while one of two travel lanes in each direction is repurposed for bus priority. These bus lanes, stretching from First Avenue to West End Avenue, would be in effect 24/7.

But enraged locals say that two specific blocks of 96th — between Central Park West and Amsterdam Avenue — are too “residential” to be outfitted with bus lanes.

“What we are saying is not every street is the same,” said Ellen Harvey, a rep for the 96th Street Neighborhood Coalition, at a Sept. 5 press conference. “We have two residential blocks here, except for one, two little stores, three little stores right over here. But that means that the people that live on the street need to have accessibility to their buildings.”

Harvey argued that if the bus lane were implemented, traffic would be “condensed to one way,” locals wouldn’t be able to get dropped off in taxis or Ubers, and children wouldn’t be able to get picked up by their parents in their cars.

“What we are asking is a rethink of this idea and a model for neighborhoods and residential areas that allows for these two blocks to not have a bus lane, and to offer us Select Bus Service” said Harvey.

She also falsely claimed that anyone parking in a bus lane for even a moment risks a $250 fine from an automated bus-mounted camera. Bus camera tickets start at $50, and only register if a car is caught by two buses passing by more than five minutes apart. Neither the M96 nor M106 have been outfitted with cameras, anyway.

City Council Member Shaun Abreu, did not appear at the press conference, despite organizers advertising to media that he would show up. Reached for comment, Abreu, who represents the community, said he hadn’t taken a firm position on the bus lane yet but argued that DOT could improve the project.

“[I] wouldn’t say I’m opposed or in favor at this point,” Abreu said in a text message. “We’ve been working with DOT and the community group on trying to find a workable solution, but think there’s more work DOT needs to do here to provide clarity about the project and to make some adjustments.”

The opponents did, however, get support from another influential West Side politician: Gale Brewer, who represents the neighboring district and Central Park in the Council, joined the protesters in opposition. She’s a former Manhattan borough president and longtime fixture of Upper West Side civic life with considerable sway over its politics.

Brewer said she is generally supportive of bus lanes, which are proven to speed up commutes — highlighting her support of lanes on 14th, 34th, and 181st streets when she was borough president. However, in this instance in her own backyard, she says she has concerns and wants a “second review.”

“In this particular case, there are concerns that we have,” said Brewer. “I think you have to look at alternatives to make the bus go faster, because that’s what you want to do at DOT.”

Some of the alternatives Brewer mentioned included bus signal priority or dedicated loading zones for deliveries.

Reached for comment, a DOT spokesperson noted that the significant majority of 96th Street commuters use mass transit — 74% don’t own cars and 68% commute via mass transit — and contended that the lane will benefit most neighborhood residents.

“96th Street is one of the city’s busiest crosstown routes for bus riders, yet at rush hours it can be just as fast to walk as it is to take the bus,” said DOT spokesperson Will Livingston. “Dedicated bus lanes will make bus service faster and more reliable for more than 15,000 daily bus riders on the corridor.”

The East Side’s Community Board 8 has given its endorsement to the project, while the West Side’s CB7 has not yet done so as it seeks to resolve “sticky” issues with the DOT, said Transportation Committee co-chair Andrew Albert. A message to CB11, which covers East Harlem, was not returned.

DOT is legally entitled to build the bus lane even without support from community boards or local pols, but doing so can sometimes cause a political thicket for City Hall.

Open Plans, an advocacy group promoting streets more geared toward pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders, called the opposition to the bus lane “out-of-touch” and “not factual.”

“If residents think this corridor should also have loading zones to further reduce chaos and congestion on the street, we’re all for it,” said Sara Lind, the group’s co-executive director. “But that should never come at the expense of a proven improvement to public transit and street design.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/